3 The Yokohama years

- 'Pupil' of Fukuzawa Yukichi -

His two uncles

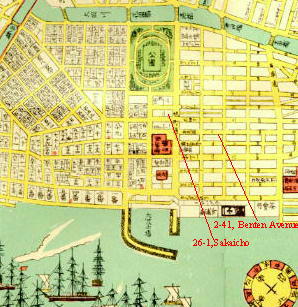

At the beginning of 1882, Takano Fusatarô, who had just graduated from Kôtô Higher Elementary School, took his first steps as a member of society, becoming a live-in office boy at Itoya, owned and run by his uncle Takano Yasaburô. The business' operations consisted of an office for the steamship company where contracts were dealt with cargo and steamship tickets as well as the accommodation and care of passengers before and after their voyages. Itoya was located at No 26-1, Sakaichô, Yokohama Ward, Kanagawa Prefecture, a prime site in the Yokohama port. It faced Nihon Ôdôri (Great Avenue of Japan), famous as the first western-style street in the country; Sakaichô was the area of three blocks between the Prefectural Offices and the park. It was close to the quayside and therefore a best location for a steamship forwarding agency and an inn. Today, the land is entirely enclosed within the property of the Yokohama branch of the Bank of Japan.

Another uncle, Takano Kame'emon also operated a steamship forwarding agency and inn business in Yokohama, at 2-41, Benten Avenue. Yokohama's largest shopping street, Benten Avenue had been on the original five avenues laid down when Yokohama was opened as a port for international trade. Known in Yokohama as raw silk traders, trading companies such as Mogi Sôbei's Nozawaya, Hara Zenzaburô's Kameya and other companies such as Maruzen that dealt in imported goods had their offices and shops here.

Let us take as close a look as we can at the two uncles. They were the men who had drawn Fusatarô to Yokohama, and Fusatarô's later decision to travel to America was no doubt due to the common traits he shared with these two uncles who, soon after Japan had opened up to the world, had left their hometowns behind and relocated to Yokohama.

First, let us turn to the two men's mutual relationship. Iwasaburô writes: "Father's eldest brother Takano Yasaburô", but this is an error. We know from the Takano family records that Kame'emon was 10 years older than Yasaburô. Kame'emon was the eldest brother, and we can surmise from Yasaburô's name that he must have been Iwakichi's third son and thus the brother immediately above Senkichi. That Fusatarô's two uncles were active in Yokohama soon after its opening as an international port is confirmed by the appearance of their names in Yokohama Town Association Diary by the well-known landowner Ono Heisuke.

The references to Takano Kame'emon note simply that every season Ono received presents from him: "one salmon", "a pair of dried mullet roe". The latter was a Nagasaki specialty and a gourmet delight, which Kame'emon must have had sent specially from his hometown. The first such gift was presented on October 21, 1870.

Yasaburô's name first appears in the Yokohama Town Association Diary some six months earlier than Kame'emon's, on April 13th 1870.

April 13th, 1870

I received notice that documents and notebooks wrapped in a calico kerchief belonging to the merchant Kihei of Rikuchû-Miyako [Iwate Prefecture], said to be a guest at Yasaburô's Nagasakiya in Sakaichô, were dropped by him while walking on Benten Avenue in Ôtachô.

The town head Ono was thus informed that a guest staying at Yasaburô's inn had dropped some documents, but what this makes clear is that at that time Yasaburô was managing an inn called not Itoya but Nagasakiya, the name Senkichi later adopted for his own inn. The fact that Nagasakiya had a guest from a port town in faraway Iwate Prefecture suggests that it was also running a shipping agency.

Yasaburô's name reappears in the Yokohama Town Association Diary the following year three times in connection with rather important events. The relevant references are as follows:

April 21 1871, Kihachi of Murataya has reported that a loan, the sum of 1,000 ryô he made this past March to Yasaburô of Nagasakiya in Sakaichô has not been repaid.

September 7, 1871, Kihachi of Murataya asked that until the money he loaned to Nagasakiya is repaid, Yasaburo's application for land should be suspended.

September 15th 1871, Itoya Heihachi sends word that in the matter of Nagasakiya's building and land in Sakaichô, the issue should remain unresolved until Nagasakiya repay his loan to Kihachi of Murataya.

These short and simple accounts do not reveal the details of the issue. However, Yasaburô clearly had failed to repay a loan, the sum of 1,000 ryô by the due date. In a separate matter, he was also obviously involved in a land and property deal in Sakaichô with Heihachi of Itoya. Yasaburô was most likely trying to purchase land in Sakaichô from Itoya and borrowed the money for it from Murataya and then was unable to repay the loan on time.

Yasaburô's name appears in another context in the chapter on 'Yokohama Merchants in 1870' in "A History of Yokohama City - Industry":

Benten Avenue Block 3, Nagasakiya Yasaburô Tea trader

Here Yasaburô's occupation is given as 'tea trader', and the address is Benten Avenue, not Sakaichô. He was most likely running the shipping agency and hotel business at Sakaichô and a tea export trader on Benten Avenue.

Incidentally, Yasaburô who had not repaid his loan, managed to overcome the difficulties and went on to successfully expand his business. Two facts bear this out: in 1884 Yasaburô was selected for the Yokohama Town Council, and of the 43 names listed as 'Leading Export Merchants' in the Compendium of "Japan's Leading Merchants, Financiers and Industrialists" (published 1887), just one name appears as a Steamship Freight and Luggage Agency - that of Takano Yasaburô. In fact, Yasaburô had already died by the time this social register was published, but he had nevertheless clearly risen to the top class in the shipping agency field. Yasaburô owed his success to the rapid development of the marine transport business. At this time, Japan's main form of transport by sea rather than by rail, and the mainstay of the sea freight business was the post service steam packets operated by the Mitsubishi Company, which was strongly backed by the government. Itoya benefited greatly from being an agent for Mitsubishi Company.

Fusatarô's time as a live-in office boy

Takano Fusatarô's five years in Yokohama, from thirteen to just under eighteen, were a very significant time when viewed in the context of his biography as a whole. In almost everyone's life, those years of dreams and ideals play a crucial role in influencing the course of later life - what kind of period it was, where it was spent, and with what kind of people. In our modern society which puts such a premium on higher education, there are many young people in their 20s who are still dependent on their parents and who can afford to spend their time 'looking for themselves', and the contribution of the teenage years to one's life as a whole has reduced somewhat, but in the late 19th century Japan, most of those in their upper teens were already fully fledged members of society. At the age of 13 one was already having to give thought to one's future.

In his 'My Brother Takano Fusatarô', Iwasaburô has the following to say about the Yokohama years. It is rather short but for what it tells us about Fusatarô's life in Yokohama and the names of his friends, it provides us with material for further investigation. However one point to notice is that the age given here is older than Fusatarô's actual age, due to Iwasaburô using the traditional Japanese way of counting ages; newborns being considered one year old, with everyone adding one year to their age at New Year's.

After graduating from higher elementary school, from age 14 to 19 my brother lived in Yokohama at his uncle's house. My brother was the head of our household so he was obliged to learn about business. As I said earlier, our uncle ran a shipping agency, so my brother first learned office work on the job. Our uncle was strict, and my brother was often hit over the head with an abacus. He was treated the same as the other employees, and his teenage years were a lot of hard work.

Yokohama was the only open port at the time, so seeing foreign ships every day and having many opportunities to come in contact with foreigners, young people in Yokohama all dreamed of going over to the United States. My brother was one of them, and he felt that at some time he wanted to go to America to study.

During the day my brother worked in the office and in the evenings studied at a commercial school. He loved studying more than anything and was a keen student at night school. One day he planned to hold public lectures at the school. He invited people such as Takata Sanae and Amano [Tameyuki], the founders of Waseda University. Among my brothers' friends at that time were Tomita Gentarô, Itô Nitarô (now Itô Chiyû, I believe, and with them he organized and sought to promote public lecture meetings. His studies at least made life happy and pleasant at that time.

Fusatarô lived in his uncle's house as an office boy, because he needed to 'learn something about business' as he was the head of the Takano family. Obviously he had to support his mother and his younger brother and was responsible for rebuilding the prosperity of Nagasakiya. All those around him expected this of him, and he resolved to meet those expectations.

However, his mother and sister were running the inn at Nihombashi-Naniwachô and daily life there was stable, so there was no great pressure on Fusatarô with regard to the family's finances. The most important thing for the future was for him to learn the shipping agency business and to that end, everyone, including Fusatarô himself, thought that working in the office of his uncle, who was experienced in the same business, would be for the best.

It was the first time in his life that he had been away from home, so he must have felt rather forlorn, but the youngsters of his own age were already responsible members of society, so he could hardly give expression to any feelings of downheartedness. At the same time, his own expectations were great and his chest must have been thumping when he moved to Yokohama. The work was attractive to him, because he was dealing with people who were either going abroad or was taking care of those who had returned home from abroad.

Iwasaburô wrote that young people in Yokohama all dreamed of going over to the United States, and Fusatarô was dealing day and night with people who were realizing their own dreams.

Meanwhile, in 1885 Itoya opened a new branch at Sumiyoshichô. The new property occupied 197㎡ twice the size of that at Sakaichô. At first I thought that the family had moved completely from Sakaichô to Sumiyoshichô, but Itoya appears on a later map of Sakaichô so the new building must have been a branch of the main hotel. It is noteworthy, however, that this new branch hotel is described as a 'station front hotel' (ekimae ryokan); it was no doubt opened in anticipation of the expansion of the railways. Here too, one senses Takano Yasaburô's foresight and decisiveness. It can mentioned in passing that Mori Ôgai stayed at one of the two Itoyas with his German lover Elise Wiegert. The couple spent the night of October 16, 1888 at Itoya on the eve of Elise's return to Germany, following her decision to call off their intended wedding.

The Early Years of 'Y School'

The formal name of the business school Fusatarô attended was the Yokohama Shôhô Gakkô (Yokohama Commercial School ), a school where one studied how to do business in English. The school was later known as the 'Y kô' (Y School) and which is today Yokohama City High School of Commerce. It opened in March 1882, the soon after Fusatarô moved to Yokohama. The school was founded and funded by Yokohama export merchants, who were striving to change the commercial arrangements that worked in favor of foreign commercial houses. They reasoned that a cadre of people needed to be trained who could conduct international business on an equal footing with foreigners in English.  The man who played a central role in establishing the School was the 37 year-old Ono Mitsukage. He was the son and heir of Ono Heisuke, the author of the Yokohama Town Association Diary mentioned earlier. Mitsukage held public offices such as the head of the Yokohama First Ward District Council, the first Chairman of the Yokohama Chamber of Commerce. He was also the General Manager of Yokohama Specie Bank; the forerunner of the Bank of Tokyo, and the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ today. Ono was introduced to Fukuzawa Yukichi by Hayashi Yûteki of Maruzen and asked Fukuzawa to recommend a suitable person to run the School. Fukuzawa responded by selecting Misawa Susumu.

The man who played a central role in establishing the School was the 37 year-old Ono Mitsukage. He was the son and heir of Ono Heisuke, the author of the Yokohama Town Association Diary mentioned earlier. Mitsukage held public offices such as the head of the Yokohama First Ward District Council, the first Chairman of the Yokohama Chamber of Commerce. He was also the General Manager of Yokohama Specie Bank; the forerunner of the Bank of Tokyo, and the Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ today. Ono was introduced to Fukuzawa Yukichi by Hayashi Yûteki of Maruzen and asked Fukuzawa to recommend a suitable person to run the School. Fukuzawa responded by selecting Misawa Susumu.

Misawa was a native of Okayama prefecture, studied Chinese classics under Sakatani Rôro, a celebrated Confucian scholar, and then English with Mitsukuri Shûhei. In April 1875 he enrolled at Keiô Gijyuku, forerunner of today's Keiô University, studied all that was available there in just over three years and graduated in April 1878. After his graduation, Fukuzawa recommended Misawa to be as a professor at the Mitsubishi School of Commerce but due to his insistence on his educational principles he did not get on with his colleagues and resigned the post. Then Fukuzawa selected him as the head of the newly founded Yokohama Commercial School, Misawa remained at the helm of 'Y School' until his death 42 years later, just after the Great Kantô Earthquake of 1923. He was known as the 'school abbot'.

There were five members of staff including Misawa when the School was established and just four students. Few young people had the time and/or financial resources to attend daytime classes. A fast track two year night course was rapidly introduced, which enrolled 14 students. Their names are unknown, but Takano Fusatarô was one of them. Nakamura Fusajirô, one of the students attending the main daytime courses, relates the following about the School in its very early days.

I heard that the Commercial School was starting so I went to take the entrance examination. I remember that the subjects examined were English and Chinese classics. I was surprised that there were only four new students enrolled. There were five teachers: the Principal, Mr. Misawa, Mr. Nagai Hisatarô, who taught English, Mr. Hatano Shigetarô, who taught arithmetic in English, Mr Suda, and a teacher who taught Chinese classics. There was also a caretaker, so six school staff in all, and there were four students. (from 'A Hundred years of Y School')

Kojima Kyûta, later a well known alpinist and author Kojima Usui, who joined the school's fourth year class and attended Misawa's classes in the late 1870s, recalled the following about the Principal's lectures:

Mr. Misawa's lectures on the theme of the book 'Self Help' really conjured up the past before us in our time. Making westerners seem to us as vividly familiar as Japanese, he exhorted us Japanese to stand up for ourselves and to be creative; we were greatly stimulated by him. It was like a new moral code for us at that time. To be frank, I heard profound things in lectures by many great scholars after that but I never again had the pleasure of hearing such fresh and lively power as in Mr. Misawa's lectures on 'Self Help'. Even now I still have those lectures in my head. (from 'An Alpinist's Notes')

As can be felt from such recollections, The Yokohama Commercial School was a place where Principal Misawa's influence was deeply felt; it could well be called 'the Misawa School'. Misawa's specialty was the lecture course in English commenting on Samuel Smiles' book 'Self Help', a best-seller at the beginning of the Meiji Era. Misawa's pronunciation of English was 'exceptional', and his ardent lecturing style with its lively use of both posture and gesture was for many years an emblem of Y School. Because Misawa's first teacher of English, Mitsukuri Shûhei, was actually a teacher of Dutch learning (rangaku), his teaching of English was by an 'anomalous method' which focused on English comprehension; this resulted in 'understanding' being pronounced as 'ondorussandeng' and 'service' as 'serubais'.

The merchants who founded the School had their own agenda, so the School's ethos was permeated by a nationalist spirit, about which Kojima Usui has this to say:

Each era has its own ethos. The Yokohama Commercial School was only a young institution, and it was naturally influenced by the ethos of that time. Mr. Misawa, who was in command, had his lyric poetry. And what was that about? Well, none of Yokohama's exports, beginning with raw silk, could be exported without depending on foreign trading firms. (Just one Japanese company, Dôshingaisha, was exporting raw silk directly itself, and its President, Mr. Takagi, we regarded as a hero.) What we all wanted was direct exports by Japanese. All the captains on foreign routes were foreigners, even on Japanese steamers. It was feared that passenger ships were not safe if captained by Japanese. A great problem was that many East Asian countries fell under western control and were occupied and enslaved by the West. Our homeland's very independence was in doubt at one time. Japan must expand and must thrust back the pressure being loaded on its head. Independence and self-respect are the watchwords of Fukuzawa Yukichi; they are also advocated by his best and loyal student, Mr. Misawa, who with his great stock of the old samurai spirit, has made them his own. [op cit]

Misawa's message was the same as that of his teacher, Fukuzawa Yukichi: the spirit of independence and self-respect (dokuritsu jison). Takano Fusatarô was therefore a 'second generation pupil' of Fukuzawa Yukichi. He had a strong interest in economics all his life and was an economic nationalist in that he emphasized the need for Japan's economic development. That way of seeing things was implanted into him at Yokohama Commercial School.

Another salient feature of the School was its emphasis on the teaching of English. Besides the English lessons themselves, there were also the lectures based on Smiles' Self Help, while even mathematics was taught using English language textbooks. The pronunciation may have been irregular, but there is reason to believe that the standard of English teaching at Yokohama Commercial School was high. One can assume that, apart from his pronunciation, the foundations of Takano's English were laid at the School.

Classmates at the School of Commerce - Tomita Gentarô

Fusatarô made many friends at the School. Those he met every day were the fast track night course students, but unfortunately, we know almost nothing of them. However, a number of the regular course students went on to become active members of the Yokohama business community, and their names are known. Besides already mentioned Nakamura Fusajirô and Kojima Kyûta, they include Tomita Gentarô, Takanashi Tôzaburô, Baba Torazô, Ôhama Chûzaburô and Watanabe Bunshichi. In its first year of operation, with both courses combined, the School numbered only 19 students, so students on both courses had many opportunities to get to know each other. Among them, one who Fusatarô became very friendly with and learned a great deal from was Tomita Gentarô. They were the same age and shared a passion for studying English and economics.

Tomita Gentarô had been born in Tokyo but had been parted from his parents at an early age and was brought up in Yokohama by his uncle Tomita Saen, who worked as head clerk at a foreign trading firm. Saen was a connoisseur of Kabuki and was known as a theater critic. While he lived with his uncle, Gentarô graduated from Yokohama Higher Elementary School and enrolled as a member of the first group of students on the regular course at Yokohama Commercial School. He was a very fast learner and soon had an excellent command of English. Along with his English ability, he showed his talent as 'an ideas man'. In 1885 when he was still at Y School, Maruzen published Tomita's book Eiwa shôbaiyô kaiwa (English-Japanese Business Conversation), an introduction to the subject. A thin volume of just 53 pages, he produced it to cover his finances during his studies. The contents consisted of the kind of simple English conversational phrases used in general stores, clothes shops, books shops, banks and trading firms as well as the names of various items found in such locations. As there was nothing else like it, English-Japanese Business Conversation was a success and was reissued several times with addenda, the number of pages finally totalling 128. A second and then third edition also appeared, each time with further reprintings.

Tomita Gentarô had been born in Tokyo but had been parted from his parents at an early age and was brought up in Yokohama by his uncle Tomita Saen, who worked as head clerk at a foreign trading firm. Saen was a connoisseur of Kabuki and was known as a theater critic. While he lived with his uncle, Gentarô graduated from Yokohama Higher Elementary School and enrolled as a member of the first group of students on the regular course at Yokohama Commercial School. He was a very fast learner and soon had an excellent command of English. Along with his English ability, he showed his talent as 'an ideas man'. In 1885 when he was still at Y School, Maruzen published Tomita's book Eiwa shôbaiyô kaiwa (English-Japanese Business Conversation), an introduction to the subject. A thin volume of just 53 pages, he produced it to cover his finances during his studies. The contents consisted of the kind of simple English conversational phrases used in general stores, clothes shops, books shops, banks and trading firms as well as the names of various items found in such locations. As there was nothing else like it, English-Japanese Business Conversation was a success and was reissued several times with addenda, the number of pages finally totalling 128. A second and then third edition also appeared, each time with further reprintings.

Tomita also published with a friend Ôwada Yakichi, Beikoku yuki hitori annai - Ichimei Sôkô jijô (A Guide to Traveling in America - Detailed Guide to San Francisco) in 1885.

The book was a translation of an American travel guide to San Francisco and the surrounding area. There were still no good dictionaries in those days and translations of various words had not yet become fixed, but one would not think that the translation had been done by youngsters of 17 or 18 years old. Compared to similar books of the time, the indications for pronunciations of place names and personal names are all close to the originals. Since his early childhood, Tomita had had daily opportunities for contact with native speakers and for learning English by ear. Takano did not only learn the basics of English writing in his class lessons but it can be surmised that he also learned oral English from his friend Tomita Gentarô or else through him. This is borne out by the fact that soon after arriving in America, Fusatarô was able to communicate with Americans quite freely.

Itô Chiyû and his circle

Another of Fusatarô's close friends in Yokohama was Inoue Nitarô, also known as Itô Chiyû, whose name was better known than that of Takano Fusatarô these days. In fact, before WWII, everyone knew Itô Chiyû, who was active in politics in the Tokyo Metropolitan Council and as a member of the House of Representatives in the National Diet. But what made him famous was the new type of professional storyteller, he was a popular figure in the early days of radio broadcasting. His topics were 'Lives of Great Persons', an account of the personalities and events of the day, like the life of Marshal-Admiral Marquis Tôgô Heihachirô and the Rebellion of Saigo Takamori. His stenographed performances were published in book form and the Collected Works of Itô Chiyû were published in 30 volumes.

Inoue Nitarô, born in 1867, two years older than Fusatarô, was the eldest son of Inoue Yanosuke, who ran a drugstore on Benten Avenue, the main street of Yokohama. He sat alongside Tomita Gentarô in class of Yokohama Higher Elementary School and graduated it in 1880. A precocious boy like Tomita, he joined the Liberal Party (Jiyûtô) in 1881 at the age of 14. His boss was Hoshi Tôru, later the Speaker of the House of Representatives. A more than competent party activist, he traveled the country giving speeches. First arrested in connection with the Kabasan Incident of 1884, the following year he was jailed in Nagoya for four months for contravening the Assemblies Ordinance and thereafter jailed or imprisoned several times in connection with the Shizuoka State Affairs Crime Incident, the Secret Publications Incident, and for offending against the Public Office Elections Act. On being charged with a crime of robbery and murder, his father explained the situation to his coachman Itô Isuke, adopted him and disinherited his son. At this period, political activists, who were forbidden to make political speeches, performed as storytellers and incorporated foreign themes such as the French Revolution and contemporary political issues into their performances. Nitarô emerged as one of the leading figures in such activities.

Inoue Nitarô, born in 1867, two years older than Fusatarô, was the eldest son of Inoue Yanosuke, who ran a drugstore on Benten Avenue, the main street of Yokohama. He sat alongside Tomita Gentarô in class of Yokohama Higher Elementary School and graduated it in 1880. A precocious boy like Tomita, he joined the Liberal Party (Jiyûtô) in 1881 at the age of 14. His boss was Hoshi Tôru, later the Speaker of the House of Representatives. A more than competent party activist, he traveled the country giving speeches. First arrested in connection with the Kabasan Incident of 1884, the following year he was jailed in Nagoya for four months for contravening the Assemblies Ordinance and thereafter jailed or imprisoned several times in connection with the Shizuoka State Affairs Crime Incident, the Secret Publications Incident, and for offending against the Public Office Elections Act. On being charged with a crime of robbery and murder, his father explained the situation to his coachman Itô Isuke, adopted him and disinherited his son. At this period, political activists, who were forbidden to make political speeches, performed as storytellers and incorporated foreign themes such as the French Revolution and contemporary political issues into their performances. Nitarô emerged as one of the leading figures in such activities.

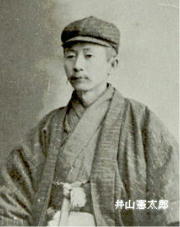

Fusatarô and Nitarô most likely got to know each other through Tomita Gentarô. Fusatarô joined a group the other two had set up. Decades later, Nitarô published his own journal Chiyû Magazine and wrote about his friends from the years in Yokohama. We shall look at his essay 'Memories of my deceased friends' in some detail as it is the only account of the young Takano Fusataro from someone who knew him closely.

I grew up in Yokohama so I have all kinds of memories of it. A number of my old friends have died. It is strange to think that very few are still alive. If I were to give an account of all my old friends, it would fill three or five copies of a magazine this size, so on this occasion I shall limit myself to just those of my closest acquaintance....

I had a classmate at Yokohama Higher Elementary School called Tomita Gentarô. My father said that studying was a waste of time for small merchants, so after I graduated from elementary school he would not let me go on to higher education. Tomita went on to study at Yokohama Commercial School, where he learned a great deal. The Principal Misawa Susumu really liked him, so Tomita was really happy. Tomita's uncle Saen used to live at Asakusa in Tokyo, but when he became a head clerk at a trading firm, he moved to Yokohama......

Three shops down the street from my house was Maruzen Bookstore. Not allowed to go to school, I had a great desire to read books; it was unbearable. I explained this to the manager Matsushita Kinjiro, and we came to an agreement that I would pay for them in instalments. I bought some books that were difficult to understand and in the evenings I would read them avidly thumbing though a dictionary. Once when I was out, my father found many of these books when he was cleaning near my desk. He also found the Maruzen receipt for the deposits. That put an end to my buying books on tick.

Ôwada Yakichi left a British trading firm and became the manager of Masujima Rokuichirô's attorney office and also became a reporter for the Jiji Shinpô newspaper. At the same time, for the sake of his studies, Tomita rented a room on the second floor of a bookbinder's shop in Aioichô. Ôwada and I would go to Tomita's room and the three of us would debate and practice making speeches there. One after another, other like-minded young men joined us. The room was a kind of gathering place for young ambitious men. I left home and moved in there. Ôwada also felt that the place he was living was like an office and moved there too. He and I plunged into research of politics and political parties, while Tomita had no time other than for his studies of economics and English.

At this another able young man joined our group - Takano Fusatarô. He was the son of the shipping agent and hotel business Takanoya, of Sakaichô. He was studying something out of the ordinary. In those days, nobody was yet thinking much about labor issues, and no scholars were doing any research in that direction. We all thought Takano was an odd fellow, but ten years later we admired his foresight. Takano wrote letters to the Yomiuri newspaper constantly and began the debate on labor questions. It is no doubt right to say that he was probably the pioneer in the field. Katayama Sen learned a lot from Takano, and besides him Takano gained many comrades. In one bound, Takano became the leading figure when it came to labor issues. Professor Takano Iwasaburô is his younger brother. Regrettably Takano Fusatarô departed this life at an early age, but his brother has taken his place and has become a leading figure, so Fusatarô can rest in peace.....

Chiyû wrote this 'Memories of my deceased friends' when he was 69, and there are some problems with accuracy in the text, but the important point is that it clearly provides evidence of the fact that Takano Fusatarô was one of the central members of the Kenmakai (Deep Study Society), alongside Tomita, Inoue and Ôwada. Kenmakai was a study group set up by Inoue Nitarô and Ôwada Yakichi who had joined the Liberal Party (Jiyûtô). There are no traces of Takano having joined the Party but it is important to recognize in the context of understanding his biography that he had direct connections with people who belonged to the Freedom and People's Rights movement.

Something else which united 'the three Taros' (Gentarô, Nitarô, Fusatarô) was their ardent desire for knowledge. As Inoue Nitaro's father had not allowed him to go on to higher education, he secretly bought western books, which he worked his way through with a dictionary. Fusatarô too, while working by day as an office boy, went to night school and applied himself to the study of English and economics. They were dissatisfied with the state of Japanese society, and taking up a critical stance towards it, they did not keep their knowledge to themselves but informed others and sought to pass it on. This was a common cause shared by these young men who had been brought up in Yokohama where there were many opportunities to come into direct contact with foreign writings in the 'enlightenment and civilization years' of the early Meiji period.

Ardent young students' love of learning

As is evident from the name Kenmakai (Deep Study Society) was a group of youngsters who delighted in studying hard together. Soon after its formation, however, it broke up and reformed itself into two groups, the Shinshôkai (Society for Promotion of Commerce) and the Kôgakukai (Pursuit of Study Group). The reason for the split is not known, but Tomita Gentarô, Ôwada Yakichi and their friends formed the Shinshôkai put their energies into public speaking activities, while Takano, in the Kôgakukai, focused on learning with the aim of self development. These two differing directions may well have been the cause of the split. Nevertheless the two groups collaborated in holding social gatherings. The Shinshôkai's Tomita Gentarô was present at the farewell party held before Takano traveled to America, so the relationships between the youngsters did not end in recriminations. It would seem that it was just a matter of differences over their fields of activity.

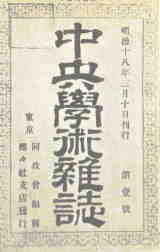

The only extant evidence of the Shinshôkai's public activity is an announcement for a 'lecture meeting' placed in the Yokohama Mainichi newspaper. While Kôgakukai had a number of its articles featured in Chuô Gakujutsu Zasshi (Central Academic Magazine), the journal of the alumni association of Tokyo Senmon Gakkô (Tokyo College), the forerunner of Waseda University. The first article about Kôgakukai appeared in No. 7 of the magazine (June 6, 1885) and included the following comment:

The only extant evidence of the Shinshôkai's public activity is an announcement for a 'lecture meeting' placed in the Yokohama Mainichi newspaper. While Kôgakukai had a number of its articles featured in Chuô Gakujutsu Zasshi (Central Academic Magazine), the journal of the alumni association of Tokyo Senmon Gakkô (Tokyo College), the forerunner of Waseda University. The first article about Kôgakukai appeared in No. 7 of the magazine (June 6, 1885) and included the following comment:

January 1884, interested people in Yokohama got together, collected money and held meetings in which they studied together, and discussed academic or commercial issues. In December the same year the number of participants increased as did the quantity of books possessed by the group.

They expanded their activities further and wanting to study political, legal, and economic issues in greater depth, they invited lecturers from Tokyo to speak on these themes and called their group Kôgakukai. Takata Sanae (literature), and Okayama Kenkichi (law) came several times a month to Honmachi Town Meeting Hall and gave lectures there.

Kôgakukai had mainly two areas of activity: one was joint purchase of reading material and the other was inviting lecturers to meetings open to the public. At the time, purchasing books was extremely expensive. For example, the best seller Keikoku Bidan (Inspiring Tales of Statesmanship) by Yano Ryûkei was published in two volumes, the first in 1883 and the second the following year. The first volume, at just over 300 pages cost 95 sen, while the second volume (over 500 pages) cost one yen and 15 sen. A high wage earning craftsman such as a carpenter would only receive about 50 sen a day, so just one volume of the book was equivalent to two or three days' pay. Groups of people up and down the country would thus pool their resources to buy a book, form reading groups and read it in turn. In the Tama area, which was then still part of Kanagawa Prefecture, many such study groups were formed, and many of them gave rise to networks of the Freedom and People's Rights movement.

In a broad sense, Kôgakukai too was a group that was connected to the Freedom and People's Rights movement, but while there were many groups in Tama aligned to the Liberal Party (Jiyûtô), the Kôgakukai in Yokohama aligned itself to the Constitutional Reform Party (Rikken Kaishintô). Speakers from Tokyo College invited by the group included Takata Sanae, Amano Tameyuki, Okayama Kenkichi and Ichijima Kenkichi. These were all young men, newly graduated from the Tokyo University (in 1886, renamed The Imperial University; 1897, Tokyo Imperial University), who belonged to the faction of Okuma Shigenobu, and after teaching 30 hours a week at Tokyo College, they would travel round the country at their own expense giving lectures. It is often said that they were in fact electioneering in various places "to build support for Kaishintô under the pretext of scholarly lectures". But in fact they only spoke on scholarly topics, or subjects related to culture and modernization, or else on practical matters. Takata Sanae's topics included "Making English the National Language of Japan" and "On Travels to the West", while the others lectured on "On Trust" and "On Commerce" (Okayama), "On National Credit" (Amano) and "Improving Letter Writing" (Ichijima). The contents of these lectures were published in Chuô Gakujutsu Zasshi, but they were void of political elements.

The young Takano learned a lot from these lecture meetings, and he was especially influenced by Takata Sanae's "On Travels to the West". I shall take this up again later, but in this connection I would like at this point to cite from the aforementioned memoirs of Itô Chiyû a passage that continues from the previous quotation:

We invited lectures from Amano Tameyuki, Takata Sanae, Yamada Yoshinosuke, Kimura Seishirô and others and heard what they had to say. We also started a debating society and debated various issues, such as the pros and cons of immigration, or the arguments for or against free trade or protected trade, so we needed to be well-prepared beforehand and had to read a lot of books, and even though it took us into some unorthodox areas, we really managed to deepen our knowledge to a considerable extent.

We know that Takano Fusatarô played a central role in Kôgakukai from the fact that his name appears as one of the four founders of the group in an appeal "Announcement for the Gentlemen of Yokohama" ('Koku Zai-Yokohama Jinshi'), when Kôgakukai was renamed as the Yokohama branch of Dôkôkai in January 1886. This was the first piece of writing in the public arena to which Takano Fusatarô's name was attached. As is clear from the bold title of Koku Zai-Yokohama Jinshi, this text, written in classical style by an ambitious youngster. The main points are summarized below.

(1) The propagation of education and scholarship is indispensable if Japan is to catch up with Europe and America.

(2) Yokohama is a place which links Japan with the rest of the world, and a heavy responsibility therefore lies with those who live there.

(3) However, many of the people of Yokohama have not awoken to the importance of studying.

(4) To overcome this situation, we volunteers formed Kôgakukai, learned much from the lecturers Okayama Kenkichi and Takata Sanae and were able to achieve substantial results.

(5) We now wish to expand the organization further and will be conducting debate meetings, in which we earnestly crave your participation.

On Feb 14, exactly a month after this appeal Kogakukai held its 6th debate session at the town meeting hall.  The motion for debate that day was "Ireland has the right of independence from England". Before the debate Takata Sanae explained the historical background to the Irish question and then the motion "Does Ireland have the right of independence from England or not?" was debated by two speakers. Inoue Nitarô argued that Ireland does have the right, while on this occasion Takano Fusatarô argued that it does not. Eventually, Takano's argument was defeated by a margin of four votes, but speaking at the conclusion of the event, Takata Sanae said that from the point of view of human feelings he would wish Ireland to be independent but that from a political perspective Ireland did not have that right, so he ended by concurring with Takano's argument.

The motion for debate that day was "Ireland has the right of independence from England". Before the debate Takata Sanae explained the historical background to the Irish question and then the motion "Does Ireland have the right of independence from England or not?" was debated by two speakers. Inoue Nitarô argued that Ireland does have the right, while on this occasion Takano Fusatarô argued that it does not. Eventually, Takano's argument was defeated by a margin of four votes, but speaking at the conclusion of the event, Takata Sanae said that from the point of view of human feelings he would wish Ireland to be independent but that from a political perspective Ireland did not have that right, so he ended by concurring with Takano's argument.

The meeting proceeded to the elections of Society officials, and Takano was elected a member of the five-man council. These five were to remain close friends even after Fusatarô returned to Japan from abroad, and for Fusatarô, his time with Kôgakukai would remain an unforgettable experience.

The Takano family in later years

While Fusatarô was living a full life, studying with those of his own age, experiencing something of society, and sharing with his friends dreams of foreign adventures, a number of changes occurred in the lives of the other members of the Takano family. We shall follow the main developments in the months and years of the period 1882-1885. As 1882 was drawing to a close, on December 29, Takano Kame'emon died. He was 55 and in the prime of life. Uncle Kame'emon had changed the destiny of Fusatarô's family. If he had not left the family home in Nagasaki and moved to Yokohama, Senkichi would not have moved up to the capital, and thus Fusatarô would not have gone to America nor would Iwasaburô have been able to study at University. The posthumous Buddhist name he received was Shinshi'in Kôzan Gengiyû-koji. The three characters Gen-gi-yû (strict-righteousness-manly) give an impression of the strict character of the man.

Takanoya, which had been headed by Kame'emon, was for a time carried on under the name of his wife Shige but not long afterwards was transferred to the name of his son Denjirô. Denjirô later took his father's name and was also known as Takano Kame'emon. He turned out not to be his father's inferior, and relocated Takanoya from Benten Avenue to Yokohama's main downtown area Honmachi. Every year he was listed among the city's highest earning income taxpayers; under his management Takanoya became Yokohama's number one hotel.

In 1881 Iwasaburô went on to enrol at his brother's school, Kôtô Higher Elementary School, and like Fusatarô before him, crossed the Sumidagawa River after leaving Nihombashi-Naniwachô and walked to his school in Ekôin. Although only a higher elementary school pupil, he felt like an adult, and would sneak into political meetings of the Freedom and People's Rights movement. He coaxed his mother buying him a copy of Keikoku Bidan (Inspiring Tales of Statesmanship) by Yano Ryûkei, which he read avidly.

Iwasaburô graduated from Kôtô School in 1884 and began his studies at Keiô Gijyuku. He probably thought that Keiô would be a good place to study English. The advice of his brother, who had been 'an indirect pupil of Fukuzawa Yukichi' [the founder of Keiô Gijyuku - transl.] may have played a role here. However, for whatever reason, after less than a year there, he quit Keiô and transferred to Kyôritsu School in Kanda-Awajichô, perhaps because the commute from Nihombashi to Mita was too much. At any rate Iwasaburô did say that he 'felt bad about' the sight of Fukuzawa Yukichi arriving at Keiô on horseback; it was not democratic, he felt. That too may have influenced his decision to change schools. Kyôritsu School was well known prep-school for Tokyo University. Compared to Fusatarô, who worked all day and could only study at night school or in study groups with friends, the younger brother Iwasaburô enjoyed a much easier environment for studying and received a solid education.

Elder sister's marriage

1885 was an eventful year for the Takano family. In January Fusatarô's paternal grandmother Kane died. Little is known of her life, but from the age of her son Kame'emon, it can be surmised that she was born around 1810 and was about 75 at the time of her death.

The month after her passing, Iwasaburô applied to enter the Army Cadet School. Hiding at the meetings of the Freedom and People's Rights movement, fired up by his reading of Keikoku Bidan (Inspiring Tales of Statesmanship), and thinking of becoming a professional soldier - just at this time one can observe the movement in the soul of a youngster living through the early Meiji period. His intention to enrol in military training school came to naught however, because he was not tall enough to meet the requirements for a soldier's height. Both Takano brothers were quite short in stature.

The biggest event for the Takano family in 1885 came in October when the brothers' elder sister Kiwa married Iyama Kentarô; the wedding took place in Hizen-Karatsu in Kyûshû. Kiwa was born on the August 27, 1866, so she was 18 at the time of her marriage.

Her husband Iyama Kentarô was the eldest son of a family of doctors who were also engaged in farming. They hailed from Tamashima village, in Higashi-Matsu'ura county, Hizen Province (Saga prefecture). After studying Chinese classics in his home county, Iyama studied German at Saga Medical School from April to October 1874. He then spent a year at medical school in Nagasaki, where he studied science and anatomy. He moved to Tokyo in November 1877 and after a year studying German at a foreign language institute, from December 1878 to July 1882 he applied himself to pre-medical studies at the Faculty of Medicine, Tokyo University. During this period he lodged at Nagasakiya, which is where he got to know Kiwa.

Her husband Iyama Kentarô was the eldest son of a family of doctors who were also engaged in farming. They hailed from Tamashima village, in Higashi-Matsu'ura county, Hizen Province (Saga prefecture). After studying Chinese classics in his home county, Iyama studied German at Saga Medical School from April to October 1874. He then spent a year at medical school in Nagasaki, where he studied science and anatomy. He moved to Tokyo in November 1877 and after a year studying German at a foreign language institute, from December 1878 to July 1882 he applied himself to pre-medical studies at the Faculty of Medicine, Tokyo University. During this period he lodged at Nagasakiya, which is where he got to know Kiwa.

In 1882 however, he fell ill with a severe case of bronchitis and had to suspend his studies and return home. He soon recovered thanks to the clean air and warm climate of his home county, and he then passed the time standing in for his father in the family medical practice and in helping with farm work. Then came an offer of a match with the daughter of a old family in town. Kentarô refused it, overcame the opposition from those around him and instead, proposed marriage to Kiwa from Tokyo.

In 1882 however, he fell ill with a severe case of bronchitis and had to suspend his studies and return home. He soon recovered thanks to the clean air and warm climate of his home county, and he then passed the time standing in for his father in the family medical practice and in helping with farm work. Then came an offer of a match with the daughter of a old family in town. Kentarô refused it, overcame the opposition from those around him and instead, proposed marriage to Kiwa from Tokyo.

Meanwhile, Kiwa herself must certainly have loved Kentarô, because to marry him, she left her home to go, quite alone, into a Kyûshû farming village, far away from her family. "Born and bred in the city, this daughter-in-law is useless" - so went the gossip of those around her. But Kiwa, supervised the work of the menservants and maidservants, and applied herself to farm work with all the farm implements and did everything to support her husband when he was out at work. She had inherited her mother's stout-hearted spirit, and the local villagers were heard to say: "She's not like a Tokyo person at all!"

The Influence of Takata Sanae's Yôkôron (On Travels to the West)

In January 1886, three months after Kiwa's wedding, Masu decided to close Nagasakiya and informed the authorities of this on February 6. The property was sold for 570 yen to the cook who had worked there. On February 9 that year, the Takano family transferred all their domicile registration from Naniwachô, Nihombashi Tokyo to Takano Yasaburô's residence at 6-80, Sumiyoshi-chô, Yokohama. The whole family upped and moved to Yokohama. Iwasaburô was still studying at Kyôritsu School, so he must have stayed in Tokyo. Masu also did not immediately move to Yokohama; first, she took the opportunity presented by the closure of the business to pay a visit to her hometown in Kyûshû and to visit her newly married daughter.

Masu's decision to close Nagasakiya and move to Yokohama was most likely in response to a request from Yasaburô.

Just at that time, Itoya had acquired land in Sumiyoshi-chô near to the Yokohama Railway Station and had considerably expanded the scale of its operations. Yasaburô no doubt wanted to draw on Masu's strength to manage this new branch of the business. After all, she had the track record of having sufficient leadership quality to have made Nagasakiya number one in Tokyo. Fusatarô's term of service in Yokohama was nearing its end and this too would have influenced the decision to close Nagasakiya and move to Yokohama.

However, on April 22, less than three months after the closure of Nagasakiya, there came a veritable bolt from the blue - Takano Yasaburô suddenly died. The details are unknown, but a possible cause of death was cholera. An epidemic was raging in Yokohama from the spring to the summer of that year; it even caused Kôgakukai to suspend its meetings.

Yasaburô had been the great benefactor of the Takano family; they all owed him a great deal and could turn to him for anything. With that reliable uncle now gone, the situation of Masu and Fusatarô in Itoya became rather delicate. Yasaburô's heir at Itoya was Sentarô, and his mother was also there. Sentarô's age is unknown but judging from his father's age, he must have been older than Fusatarô.

The circumstances are unclear, but in the end Masu decided to terminate the move to Yokohama, rented a house near the Imperial University and started a students' accommodation business. Nagasakiya had originally accommodated students; this now became its core business. Masu was most likely thinking of restarting Nagasakiya, as Fusatarô was now a young man who had been at his studies for five years and had become a fine heir for the family business. But it was at this point that Fusatarô asked for permission to realize his long-cherished desire to go to America, which Masu acknowledged. She recognized that while Iwasaburô, her younger son, had been allowed a free rein to study as much as he wished, his elder brother had been required to work hard as an office boy. While she was still healthy she wanted to be able to help Fusatarô fulfil his own wishes.

The problem was the cost of the trip to America. Even the cheapest tickets (third class) cost US$50. In June 1886 $40 was about ¥50, so the cost of a third class ticket was ¥62-63. Furthermore, 'crossing the ocean' was not simply a matter of the cost of the sea voyage; there were also accommodation and living expenses in America to consider; all in all, a sizeable sum would be needed.

How much did it actually cost at that time to travel to America? There is a book which answer this question in full. That is Come Japanese! - A Guide to San Francisco (Kitare Nihonjin - Betsumei Sôkô Tabiannai), published just at the time Fusatarô was about to travel to America. This Meiji period version of the Lonely Planet Guide gave concrete details of items needed for the trip and their prices: two suits of western clothes, one pair of shoes, three shirts, three pairs of long johns, a hat, a dozen collars, pairs of cuffs, and handkerchieves, a set of writing implements, a bag, and a blanket - a grand total of 84 yen and 3 sen. When dictionaries and post-arrival spending money of $30-40 were included then the total came to about 150 yen. For ordinary people this must certainly have been a large amount. It is not easy to say exactly how much 150 yen was worth by today's standards, but it may have been around 5,000,000 yen. A rice cake or bean jam dumpling (daifuku-mochi or manjû) cost 5 rin [1 rin = 1/1000th yen - transl.], so with 1 yen one could buy 200. A bowl of buckwheat noodles (kakesoba) cost 1 sen and an eel on rice dish (unajû) 20 sen. Fusatarô himself would have saved some money for this eventuality, but he was only an office boy and, having many friends, the money he would have saved would have amounted to little. Most of it he would have got from his mother as part of the deposit from the sale of the house.

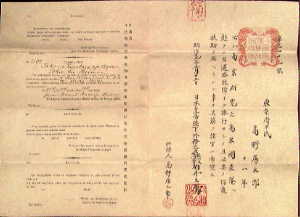

Once he had the money for the costs of his journey, the next step was the passport, which he obtained on Nov. 25 1886. In 'the purpose for travel' is written 'business research'. Young Japanese heading for America in those days had all sorts of motivations, but perhaps it could be said that in general, there were two broad types of people. One was the 'overseas student' whose goal was study. This was a difficult path if one did not have the any financial room to maneuver. Yet compared to Europe, traveling to America, and especially the West Coast, was relatively cheap, and one could work while studying so that if one had the mental and physical stamina and strength to cope with a certain amount of poverty and hardship, one could get an education even if one started with nothing. Like Katayama Sen, one could, with some hard studying, graduate with a degree from an American university. Most of them failed and dropped out on the way and only a few achieved their goals.

The second type were the migrant workers, who worked efficiently to save money over a short period of time with aim of getting ahead in life. Among them were shoemakers and tailors of western clothes who sought to hone their skills in a country where those skills were traditional. On returning to Japan, they would advertise themselves as having trained or worked abroad and would benefit from such experience and reputation.

Objectively speaking, that is, from the circumstances of his lifestyle, Fusatarô was in the 'migrant worker' category, but subjectively, he would have regarded himself as being an 'overseas student'. While working he assiduously studied English and economics. He did not close his eyes to higher education, but had private lessons in English and studied at San Francisco Commercial High School. He chose this path because he felt a responsibility towards his mother and his brother and because he had no opportunity to take the route of a regular school education. Those around him were expecting him to revive the fortunes of Nagasakiya and Fusatarô, naturally enough, intended to meet those expectations.

One reason for choosing this rather unique course as an 'overseas student' was the influence he received from Takata Sanae's Yôkôron (On Travels to the West). The point that Takata emphasized in his article was "those who cross the ocean ought to make it their principle to observe all things, apply themselves thoroughly to all things, but not to aim to study all things at school." Because in schools in America and Europe it was required to study theology and Latin, which, Takata argued, "for us undeveloped East Asian peoples who seek to apply ourselves industriously to what is practical and utilitarian, such subjects are of no benefit." It was a waste of money and time to study these subjects. Rather, "one should pursue one's studies relying on the counsel of one's experienced seniors and one's own studies." Takata also argued that "one needn't bother about getting things like degrees."

Such views show Takata's 'discernment', but in view of the way in which Japan later rapidly became a society that is heavily focused on educational status, one can question whether such advice was appropriate. Fusatarô's English was far superior to that of most of his contemporaries. However, in America, his only educational attainment was to graduate from the limited course of the San Francisco Commercial High School, and after returning to Japan, this 'educational attainment' was not valued by any employer. If he had had a regular higher education his life would no doubt have been much more successful in mundane terms. However, Fusatarô followed Takata Sanae's teaching and in doing so, left his mark on history. He 'observed' American society with care and depth and 'applied himself' to the achievement of an excellent level of English ability. Through his own observations, he discovered the importance of the role of labor unions and consumers' cooperatives, and while seeking to introduce these to the people of his own country, he made great practical efforts to organize them. In so doing, he ultimately became the progenitor of Japan's modern labor unions and the pioneer of the cooperative movement.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), Chapter 3. Yukichi no mago-deshi - Yokohama jidai

|