5 The Founding of the Friends of Labor

- The beginning of the Japanese labor movement -

A book that chaged his life

After a colorful start to a business which folded in just six months, Fusatarô's departure from San Francisco was almost in the manner of a sudden flight. To remain in a city where there were many Japanese and visitors from Japan and to have fingers pointed at him as a failure was unbearable for the proud young fellow. But to simply return to Japan was unthinkable. He would have to stay in the United States to work in order to pay off the various debts he had accumulated. It was at this time that he headed for Point Arena. With its memories of the happy summer spent there two years previously with the Brayton boys, it must have seemed a nostalgic place for him, which, with its giant redwoods around the beach and old friends, warmly greeted the forlorn youngster. At that time in Point Arena, Fusatarô came across a book which was to change his life. He wrote about this in a letter to Samuel Gompers dated Dec.17, 1897.

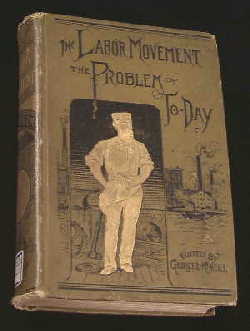

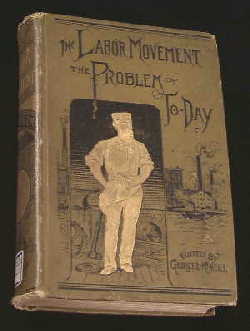

It was in the year of 1889 while I was working at saw mill in California when fortune favored me to receive a book entitled "Labor movement the problem of to-day." Perusal of the book aroused my interest to the movement and sharpened my sense to the wrongs that are endured by Japanese workers.

One could say that Fusatarô's failure in the world of commerce led him to the labor union movement. His guide was that book edited by George E. McNeill, The Labor Movement - The Problem of Today (A. M. Bridgman & Co.; the M. W. Hazen Co., 1887, Boston, New York).

George E. McNeill was born in Amesbury, Mass., August 4, 1836; he was a labor leader in New England and was a member of the grand Eight-hour League, and founded the Workingmen's Institute; he was appointed first Deputy of the Massachusetts Bureau of Statistics of Labor, under General H. K. Oliver, serving until May, 1873; for eight years. Later he joined Knights of Labor and was appointed Treasurer of District 30, in 1884 and was subsequently made District Secretary -Treasurer until 1886.

The Labor Movement - The Problem of Today had been published in 1887. It was a solid compendium of the American labor movement at the time, consisting of more than 600 pages in 25 chapters and appendices.  The book deals with the various labor and social problems America was facing in that period, with a focus on the workers' movement, and mostly written by contemporary labor leaders. There seems little reason to doubt that Fusatarô gained a comprehensive understanding of the labor movement from this book. Incidentally the Internet Archives has made the full-text of the book available online. The book deals with the various labor and social problems America was facing in that period, with a focus on the workers' movement, and mostly written by contemporary labor leaders. There seems little reason to doubt that Fusatarô gained a comprehensive understanding of the labor movement from this book. Incidentally the Internet Archives has made the full-text of the book available online.

Nevertheless, the Takano's statement cannot be accepted merely as it stands, because it was the kind of book that only someone with a prior interest in the labor movement would have had access to a copy. It was neither an easy-to-read piece of fiction nor a work like the Bible that many people referred to. Yet this was a book that Fusatarô himself personally acquired. The price is unknown, but from the cloth hardback cover, and the title on the spine, which, like the cover illustration of a blacksmith, was engraved in gold leaf, it was clearly a high quality publication and certainly not cheap. One cannot help but conclude that Fusatarô must have already had an interest in the labor movement before purchasing such a book. When and where did he get to know of the labor movement, and how did this interest arise? These questions, which obviously relate to how and why Takano Fusatarô would become Japan's first labor union organizer, go to the heart of the theme of this book; they call for a chapter to themselves.

Takano's interest in the labor movement and his experience of poverty

Before that, however, there is one question that needs consideration. This is the view which maintains that Takano Fusatarô became interested in the labor movement because he had lived a life of poverty in his youth and had experienced hardship as a foreign worker in America. This view is argued by Stephen E. Marsland in his book The Birth of the Japanese Labor Movement - Takano Fusatarō and the Rōdō Kumiai Kiseikai. In fact, a similar view was strongly held by none other than Takano's brother, Iwasaburô. In his article Ani Takano Fusatarô wo kataru (My Brother Takano Fusatarô) and Torawareta minshû (An Imprisoned People) , he emphasized that Fusatarô had led "a hard life as a youngster", that his participation in the labor movement was "behavior based on his own experience as a worker", and that Takano Fusatarô was not a born labor unionist; but on the contrary, his destiny led him to the movement from his early childhood onwards. This testimony from his closest relative cannot be ignored.

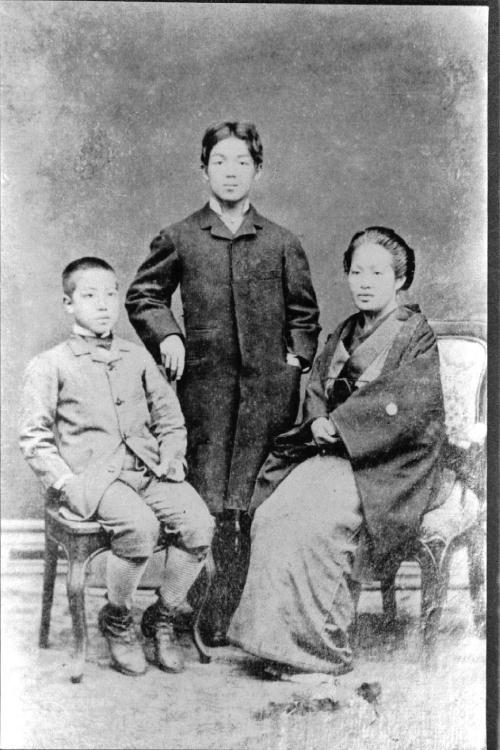

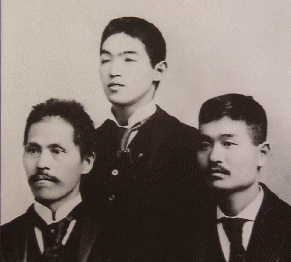

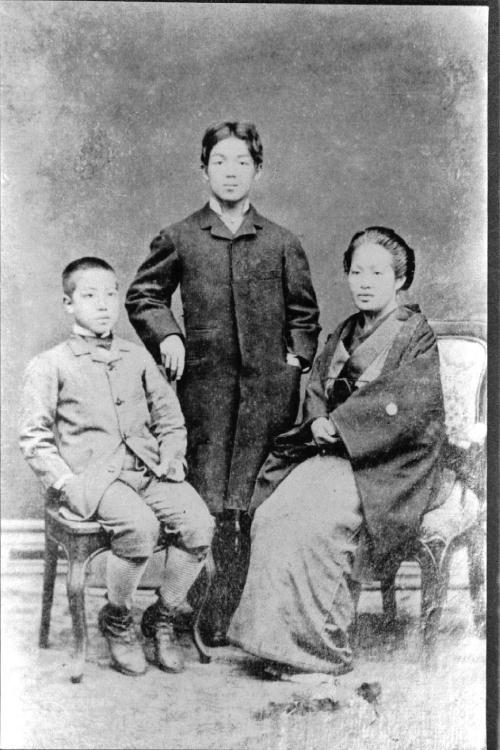

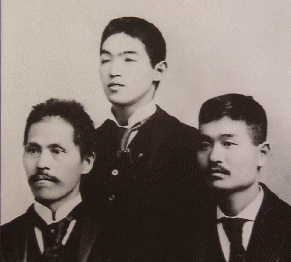

However, the claims of both Marsland and Takano Iwasaburô do not match the historical facts. According to Iwasaburô's memoirs, on completing higher elementary school, Fusatarô was sent to live with his uncle, where he was made to work like a servant. Reading this, it would seem that Fusatarô's "hard life as a youngster" was an indisputable fact. But that would be to see things from the perspective of today's social criterion of high academic achievement. Those who graduated higher elementary school in the 1870s and 1880s were considerably fewer in number than university graduates today. If the Takano family had really been poor, then Fusatarô would not have been able to go overseas nor would Iwasaburô have been able to go on to do post-graduate studies at the Imperial University. Take a look at the photograph here.  From the age of the two boys, it is supposed that this was taken at the time of Fusatarô's higher elementary school graduation, that is, just after the time when, according to Iwasaburô's memoirs, the Nagasakiya was burned down in the great fire, and the family were "cast out naked into the street." And yet, this picture shows that the Takanos were well-off, because the boys are well dressed in costly western clothes and even shoes. This picture alone illustrates that claims of "hard life as a youngster" are difficult to credit. From the age of the two boys, it is supposed that this was taken at the time of Fusatarô's higher elementary school graduation, that is, just after the time when, according to Iwasaburô's memoirs, the Nagasakiya was burned down in the great fire, and the family were "cast out naked into the street." And yet, this picture shows that the Takanos were well-off, because the boys are well dressed in costly western clothes and even shoes. This picture alone illustrates that claims of "hard life as a youngster" are difficult to credit.

Iwasaburô's emphasis on the poverty of the Takano family is not exactly without foundation. There was his own experience of poverty during his student years. Seen in relation to Japanese society as a whole, the Takanos were certainly not poor, but compared to that of his friends, Iwasaburô's student life was indeed poor; everything had to come from the money his mother made running a boarding house and from his brother's remittances. He could not afford to buy books freely and was constantly short of pocket money. It could not have been easy for him to socialize on an equal terms with his friends, such as Onozuka Kiheiji, who later became the President of the Tokyo Imperial University and was the son of a wealthy landowner.

In America, Fusatarô was also saddled with debts and hard-pressed to remit money home, his life was certainly not an easy one. Yet the reason why Fusatarô became interested in labor unions was not due to the experience of being a poor migrant worker. In his first report on the American Federationist, The Labor Movement in Japan, he wrote the aims of the labor movement as follows.

Really, I do not argue for the necessity of a labor movement because the condition of laborers is pitiful and their environment is intensely inimical to their interests, nor because of humane sentiment. But I do argue for it because the future prosperity of the nation does demand it and future achievement of civilization does necessitate it.

All written statements on labor issues by Fusatarô argue the need for labor unions entirely from the standpoint of an intellectual who is concerned with the prosperity of his mother country. The nationalist Takano focused primarily on the need to build the wealth and strength of the State of Japan. To that end, he argued, Japanese workers' wages, which were too low, needed to be improved, and this inevitably required the existence of labor unions. In my judgment, until his death, not once did Takano Fusatarô ever regard himself as 'a worker'. His sense of himself was consistently that of a 'student' and an 'intellectual'.

Meeting the trade union

Let us consider in more depth the theme raised in the previous paragraphs - why Takano was drawn to the labor movement. He himself explained it in his first letter to Samuel Gompers, dated March 6, 1894:

Having been attracted by the well doings of American Workingmen since my arrival in this country a few years ago, my thought has been turned upon Japanese laborers whose condition viewed from social and material standpoint is most pitiful and has caused me to determine to try to better their condition upon my return home. In order to do so, I intend to study as much as I can of American Labor movement while I live in this country.

He says that the reason why he became interested in the labor movement was because he had noticed that American workers enjoyed a better standard of living than their counterparts in Japan. He was amazed by the high level of mechanical culture in America, symbolized by elevators and cable cars and by the rows of villas and the luxurious lifestyles of the wealthy, but what made the strongest impression upon him was the high standard of living of the common people. Working at the Garcia Sawmill in Point Arena, he became aware of the huge gulf between the daily life of the mass of people in Japan and that of ordinary Americans. Why was this gulf so great? For Fusatarô, with his yearning for Japan to become a wealthy nation, this became a vital question.

But there is still something problematic about Fusatarô's own explanation here. Would he really have moved in his thinking so readily from an awareness of the high standard of living of American workers to the existence of labor unions? Without any particular knowledge of labor unions, he was surely unlikely to have made the connection between the two. So when, where and how did Fusatarô get to know of labor unions? My own supposition as to when Fusatarô first noticed the existence of labor unions is that it was when he was in San Francisco in the autumn of 1888, because it was at this time that he first met the man who was to be his lifelong friend and comrade, the shoemaker Jô Tsunetarô. Jô had taken part in the shoemakers' labor movement in Japan before going to America and, wanting to carve out a new path for Japanese shoemakers, he made his way to San Francisco in the autumn of 1888 to work and learn. His first job in America was washing dishes at the Cosmopolitan Hotel. At that time Takano was working for the hotel as a 'pulling guests', so Jô must have found the job by Takano's introduction. They were both from Kyûshû and had both lived in Nagasaki so they soon hit it off.

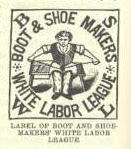

It was just at that time that the anti-Chinese migrant movement was at its height on the west coast, and at the forefront of the movement were the labor unions. A leading role in the effort to exclude Chinese migrants was played by the 'Boot and Shoemakers White Labor League'.  They were known for their tactic of sticking a 'union label' on shoes that had been made by white shoemakers and calling for boycotts of products made by non-union [i.e. non-white] labor. Such unions would certainly have been a topic of conversation between the shoemaker Jô and Takano. Proof exists in fact that more than anything, it was the American shoemakers' campaign to exclude Chinese labor that first made Takano aware of the power of labor unions. His first report about the American labor movement, titled 'Hokubei gasshûkoku no rôeki-shakai no arisama wo josu' (A View on Labor Societies in the United States of America) begins as follows: They were known for their tactic of sticking a 'union label' on shoes that had been made by white shoemakers and calling for boycotts of products made by non-union [i.e. non-white] labor. Such unions would certainly have been a topic of conversation between the shoemaker Jô and Takano. Proof exists in fact that more than anything, it was the American shoemakers' campaign to exclude Chinese labor that first made Takano aware of the power of labor unions. His first report about the American labor movement, titled 'Hokubei gasshûkoku no rôeki-shakai no arisama wo josu' (A View on Labor Societies in the United States of America) begins as follows:

When we look at the political history of the United States, we become aware that workers exert a great influence on the politics of this country. The Chinese Exclusion Act came about as a result of this powerful influence of the workers.

Takano did have some direct contact with union members at Point Arena, and it is thought that he got to know of McNeill's book The Labor Movement - The Problem of Today through them. The population of Point Arena was only 500; it was not a place with a bookshop that would sell such a book. However, it did have a branch of the Knights of Labor, an organization in which McNeill was a leading official. One can only imagine that Fusatarô was told about the book by a member of the Point Arena branch of the Knights, who happened to have a copy.

The Knights of Labor were a workers' association typical of the American scene in the 1880s. Formed in 1869 as a secret society, it 'went public' in 1882, rapidly expanding thereafter to a membership of 700,000 by 1886. It aimed to become the broadest organization of workers irrespective of race, gender, or skill level. Women, blacks, unskilled workers, and even employers were all free to join. Its leaders emphasized good labor-management relations and opposed strikes, but strikes nevertheless were organized by lower level groups and branches of the Knights. The movement promoted social reform in terms of demands for the reduction of working hours, the abolition of child labor, and cooperative unions. In the 1890s craft unions within the Knights' organization formed the American Federation of Labor and asserted their independence from the Knights, which entered into a period of rapid decline. But in Mendocino County, California, where Point Arena was located, the Knights remained active.

In burnt-out streets - Seattle

Fusatarô's second stay in Point Arena was not long. By the autumn of 1889 at the latest, he had moved up to Seattle - the site of the First General Strike in America of 1914 and the stage of the 'Battle in Seattle' in 1999. For the management side, Microsoft has its headquarters near here, and from Seattle the Boeing Company, Amazon.com and Starbucks have spread their activities worldwide. It is still today a city of venture capitalism full of pioneering spirits.

But when Fusatarô arrived in town, there were blackened timbers everywhere, the smell of smoke filled the air. The town had recently been hit by a great fire.

At 2:40 pm on June 6, 1889, in the basement workshop of James McGough's furniture-making and paint retail shop, someone had been heating up some glue with a gasoline light, when the pan boiled over, and the fire spread within seconds. From the first floor it passed to the second and then to the neighboring bar, where whisky barrels exploded. In just 20 minutes from the start of the fire, a whole block, from Madison Avenue as far as Marion Street was aflame. The city's luck was out, and so was the tide, which made it impossible to draw water from the sea. The fire raged, fanned by a strong north-northeast wind, while the water pressure in the water system was low due to seasonal water shortages. 25 blocks of the city - about 500,000 ㎡ (123.5 acres) - were completely burnt out, including the commercial quarter and the Opera House, of which Seattle residents had been so proud. As the fire occurred in broad daylight, there were no casualties, the only blessing amidst disaster, but in no more than 11 hours downtown Seattle was reduced to ruins.

However, the fire had only a very temporary negative effect on the city's economy. After the disaster, wooden houses in Seattle were replaced by brick ones, improvements were introduced all over the city including higher pressure in the water system, and in a short period the city was rebuilt. At that time, the Pacific coast still had something of the characteristics of the frontier. Although well inset from the ocean, Seattle in particular, on account of its excellent deepwater harbor in Puget Sound, was growing rapidly as a lading port for lumber and coal. Export destinations included San Francisco and all regions of the USA as well as Japan, China and other countries around the Pacific. In 1880 Seattle had a population of just 3,533; by the time of the fire it had swollen to 31,000. The fire robbed 500 people of their jobs, but the rapid rebuilding of the city required many hands, and according to the national survey of 1890, the year after the great fire, Seattle's population had risen to 42,837.

During this period, most of those drawn to Seattle were white people, but among minority groups, those who stood out were Japanese, reflecting the fact that in that region the campaign to exclude Chinese migrants was especially vigorous. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century anti-Chinese feeling spread throughout the United States. The Chinese habits of keeping their distinctive pigtail hairstyle and their own easily recognizable Chinese dress, as well their tendency to congregate in their own areas and avoid mixing with others became bones of contention. Chinese laborers had from early on been brought in to work under harsh conditions on transcontinental railroad construction sites and in mines in the mid-West, where they had borne up the American economy at its lowest levels. However, for white workers, Chinese labor meant lower the wage levels and the loss of jobs. This accounted for the widespread movement to exclude Chinese migrant workers, from the East Coast to all areas of the West Coast.

Quite a number of labor organizations within the American labor movement were founded with the specific aim of excluding Chinese immigrants. The most zealous such organizations were to found in State of Washington. Their activities were symbolized above all by the 'Seattle anti-Chinese riots'. Late in the evening on Saturday, February 2, 1886, gangs of white blue collar workers, including many members of the Knights of Labor, rampaged through Chinatown, dragged Chinese out of buildings and herded them down to the docks and forced them onto ships bound for San Francisco. Federal troops had to be called out to suppress the rioting. Japanese then moved to Seattle to fill the gap left vacant by the Chinese who had been forced out through this application of sheer violence. In the year following the riot some 200 Japanese arrived in Seattle, and the numbers steadily increased. Takano Fusatarô was one of them. Due to the shortage of labor in Seattle, wage levels among the Japanese in Seattle were considerably higher than in the San Francisco area. In a letter to Takano Fusatarô from Albert Brayton at Point Arena, we read:

I am glad to hear that you got work. $45 is good wages and you had better stay with it. I could to work now for a $1 a day.

Takano must have moved to Seattle on hearing of the boom going on there. From the address of the letter, the job referred to must have been restaurant work. Fusatarô writes in a letter to his brother Iwasaburô that the cook's English was poor, so he himself with his good English most likely worked as a waiter. But he did not stay long there either. Soon after the New Year, he moved to Tacoma. He was certainly a young man with itchy feet.

A Tacoma Chophouse

In the spring of 1890, Fusatarô arrived in Tacoma, about 80 km south of Seattle. It was a port town with splendid views of the majestic form of the nearby Mt Rainier (4392 m), which Japanese-Americans call 'Tacoma-Fuji'. There is a colorful little essay that describes summer in Tacoma and gives us an impression of what the town of Tacoma was like at that time. As it was written in the year before Fusatarô moved to Tacoma, it presents us with a picture of the town that he saw. There is a colorful little essay that describes summer in Tacoma and gives us an impression of what the town of Tacoma was like at that time. As it was written in the year before Fusatarô moved to Tacoma, it presents us with a picture of the town that he saw.

This is a red town. The buildings are built of limestone and redbrick and the roofs are also colored red. The green of the trees which one sees everywhere further vivifies this redness. The town is sited on a hill. The blue sea spreads out below one's gaze, while behind, dense forests of green dominate the landscape. The town of Tacoma rises above this gloomy primitive forest like a tower with red gunholes. The blue of sea and sky, the green of the trees, the red houses - wherever one went, the smell of fresh paint met one's nostrils along with the aroma of sawdust from newly cut timber.

[abridged from A History of Tacoma and Pierce County]

We know of Takano's move to Tacoma from the fact that his report for the Yomiuri Shimbun titled "A View on Labor Societies in the United States of America" was prefaced with the words 'from Tacoma, Washington State, April 30', 1890. The envelope of a letter to Iwasaburô of August 8 that year bears the address : 'Tacoma Chophouse, 1122 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma, Washington'. The last part of the letter contained the following lines:

I started a new business over a month ago, which is gradually making progress. Recently, I have been making about $100 a day, but due to having to pay the wages of the 10 staff and the rent of $200 and refurbishment costs incurred in starting the business, it looks like it will be a while before it turns a profit.

He writes "I started a new business" but in fact this was not a shop but a restaurant. The term 'chop house' comes from cutting pork and lamb chops and usually referred to restaurants that mainly served meat dishes. From the fact that he writes not about wages but about running costs and profit, it can be surmised that he was no mere employee there but had some responsibility for the management. But he was not the main manager. The Tacoma Town Register records: "Saito Shukichi, restaurant. 1122 Pacific Avenue, domicile same address". The two probably shared the managerial responsibilities - Saitô was probably the owner and chef, while Fusatarô would have been in charge of such things as purchasing and dealing with customers. Pacific Avenue was Tacoma's only main thoroughfare; photographs of the period show a row of three-story stone buildings with tramcars running along the street. With a rent of $200 and 10 staff, it would have been a large restaurant. Pacific Avenue was Tacoma's only main thoroughfare; photographs of the period show a row of three-story stone buildings with tramcars running along the street. With a rent of $200 and 10 staff, it would have been a large restaurant.

At the time Tacoma's rate of expansion was almost outpacing that of Seattle. Because it became the western terminus of the Northern Pacific Railroad, in the competition with Seattle and Portland, Oregon. Like Seattle, Tacoma faced onto Puget Sound and was also equipped with an international port capable of coping with big ships. It had the advantage that ships from Asia arrived here two days earlier than at San Francisco. Being a hub for the two principal modes of transport of the age, railroad and shipping, Tacoma developed as an important focal point for transport linking the American continent and all destinations across the Pacific.

Although the American economy was suffering in the slump of the late 1880s and early 90s, Tacoma was riding the crest of a boom. New railroad workshops joined the earlier sawmills, and iron foundries and engineering yards sprang up to service the new industry. Tacoma also outstripped Portland, which had been the leading exporter of cereals until that time. Grain warehouses and milling plants appeared here and there in the town, enabling wheat and wheat flour to be exported from Tacoma all over the world alongside lumber and coal. The population rose rapidly from 9,907 in 1886, 10,508 in 1887 to 12,500 in 1888. By the time Fusatarô moved there in 1890 it had trebled to 36,000 in just two years. The Tacoma chophouse opened for business in the very middle of this boom.

Aiming to become an entrepreneur

At the end of September 1890 Fusatarô moved again, just six months after relocating to Tacoma. He left the city on September 30 and arrived back in San Francisco on October 3. At a time when transcontinental trip of 5,600 km from San Francisco to New York, it took only five and a half days, on the West Coast between Tacoma and San Francisco, just over 1,200 km, he took all of four days. It seems Fusatarô really enjoyed traveling. But what was he thinking of in returning to San Francisco? He had helped open a restaurant in Tacoma's boom time in a prime location in the city, and business had gone well, yet after only three months there he quit - at first glance, his actions are not easy to fathom.

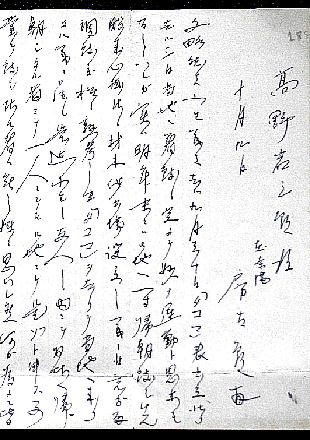

In fact, Fusatarô gives us a detailed explanation of his movements.  Until now the story has many times been hampered by a lack of source documents, but from here onwards the situation changes. 26 letters and postcards addressed to his brother survive from the period of just over two years from August 1890 to September 1892, and they inform us in quite some detail as to his situation: not only what he did and when, but also what he was thinking in those situations and what hopes and desires he was harboring. Generally speaking, Fusatarô's writings in Japanese tend not to reveal his feelings, but this particular batch of correspondence is rather different in this respect; it includes some very direct expressions of what he was feeling. Thus far, I have avoided lengthy quotations from source documents, but this correspondence requires rather more detailed citation because it reveals to us something of the man's heart and soul. First, a letter of October 9, 1890:

Until now the story has many times been hampered by a lack of source documents, but from here onwards the situation changes. 26 letters and postcards addressed to his brother survive from the period of just over two years from August 1890 to September 1892, and they inform us in quite some detail as to his situation: not only what he did and when, but also what he was thinking in those situations and what hopes and desires he was harboring. Generally speaking, Fusatarô's writings in Japanese tend not to reveal his feelings, but this particular batch of correspondence is rather different in this respect; it includes some very direct expressions of what he was feeling. Thus far, I have avoided lengthy quotations from source documents, but this correspondence requires rather more detailed citation because it reveals to us something of the man's heart and soul. First, a letter of October 9, 1890:

I left Tacoma on September 30 and arrived here in San Francisco on October 3. I daresay you think this is odd behavior, but actually, I am thinking of returning to Japan for a time at the end of next year, when I would like to look seriously into the possibility of setting up a lumbering business, something I have had on my mind for some time. After serious reflection on various issues in this connection, I left Tacoma and moved here.

Among those of my friends who have returned to Japan, not a single person is running the business he wanted. I have wondered why it is that when everyone went back to Japan, things turned out as they did, but I have not been able to identify a particular reason. How businesses are set up in Japan may be one reason which makes it difficult for pioneers to start enterprises, if so, then I am afraid that when I return to Japan next year, I will encounter the same difficulties and be unable to achieve my goals. So I have come to feel that in order to prepare for such a situation, I must study as much as possible while I am here in America.

Of course, I do not imagine that I shall be able to engage in any specialist studies at a high level, but I would like to study at a level which would enable me, on my return to Japan to be able to avoid the charge that I have lived in America yet cannot converse with foreigners. There was no such school in Tacoma that could help me in this respect, which is why I have returned to San Francisco.

Once I have found employment, I intend to study at the San Francisco Commercial High School (which has no monthly fees). If I study there for four or five months, my English conversation ability will have greatly improved and I should be able to travel anywhere and engage in conversation without impediment. When I got here from Tacoma, I had various outlays so I now have some $25 left. I shall add to that the money I will make every month as a 'school boy' and while attending the school, I shall remit some money to you. If this does not work out and the money set aside runs out, I shall quit the school. At the moment, I think I shall need to study for four or five months. It may be that I have to quit after two or three months; at present, I can only hope it will be longer. Among the jobs that we Japanese can do here, cooks make the most money, but I have no skill as a cook nor have I worked as a cook. I shall therefore have to use the opportunity of working as a 'school boy' to study American cooking so as to be able to earn more money. I have not found a job yet so I have not much to report, but I wanted to explain simply the reasons why I have come to San Francisco.

Yours etc.

It had been only two years since the failure of his Japanese goods store and its subsequent debts, and he had not yet finished paying off those debts, still he was thinking of starting a lumbering business in Japan. He probably got this idea from his working experience at the Garcia Sawmill in Point Arena. As usual, he was still chasing his dreams, the letter shows that he was nevertheless imagining an enterprise for the future and was laying the groundwork of preparation necessary to achieve his goal. A lumbering business was not something that could be realized easily, so before embarking on it, he intended to return to Japan to make a thorough research of what the venture required. He also gave some thought how to avoid the charge that he have lived in America yet cannot converse with foreigners, he decided to embark on a formal study of English.

Fusatarô's letter shocked his family and relatives back home. At that time, the Takano family was under great financial pressure. Not only had Fusatarô's business failed despite the family money he had used up, Iwasaburô's education was also costly. The family had had to ask around to acquaintances for loans to get through their present difficulties and had had to endure the hardship of relocating to cheaper accommodation. Fusatarô's remittances obviously provided a lifeline. But now he had left his well-paid job in Tacoma and was talking of studying at a school in San Francisco. And on top of that, what really unsettled them was that he was planning an incredible scheme to set up a lumbering enterprise. His Japanese goods store had nearly ruined the Takano family, but it was obvious that a lumbering business would be a large-scale undertaking far beyond the family's financial resources. On hearing of Fusatarô's plans, his brother-in-law Iyama Kentarô soon sent him a critical letter.

But Fusatarô stressed that his plan was the result of some serious thought and sought to secure his brother Iwasaburô's cooperation. He set down his thinking in a letter of Dec. 11th 1890:

I'm sorry to trouble you at this time of the year but would you mind looking into something for me? I've been thinking for some time of setting up a lumbering business after I return to Japan. Recently, I've been doing nothing but checking out the prices of the machinery necessary for such a venture. Naturally enough, while I'm here in America I can't draw up any clear plans, but after thinking a lot about it, I've decided that once I've got my travel fare, I'm going to return to Japan and travel round the country to see whether my plan is practicable or not, and if it is, then I'll set up a company, but if it isn't, then after I have confirmed all that is necessary to realize my plan, I shall return to America and look for ways to get together the necessary capital......

What I want to ask you to do for me is no small thing, and there may be some things that are not immediately clear, but if you can, please look into things for me and write back as soon as possible. The first four points can be checked in a statistical yearbook. To do this, please borrow the latest yearbook from the library.

Also, as there are various other things that I would like to check, it would be excellent if you could buy a copy of the yearbook and send it to me. I'll send the money for it together with my next remittance.

1. The holdings of state-owned mountain and forest land in Japan - their location, area and value.

2. The location and value of land where lumbering is possible in privately-owned mountain and forest land in Japan.

3. The total annual demand for lumber in Japan and its average value.

4. The average income of loggers.

5. The costs of a trip from Tokyo along the San'in and San'yô highways to Kyûshû and Shikoku and back and of a trip around the Kantô region.....

Fusatarô's 'Cry from the Heart'

This letter crossed the ocean at the same time as one from Iwasaburô that was critical of the plans of a 'lumbering business'. When Fusatarô read this, he became agitated and penned a long reply putting the counter-argument and asking for his brother's understanding. For a man who normally did not give expression to his feelings in writings, this one letter really showed how he felt. For an understanding of what kind of person Takano Fusatarô was, this is a most important and revealing document, so despite the length, I shall cite the main section in its entirety.

Thank you very much indeed for all your views with regard to my return to Japan. I have given them much thought. I suspect that your view as to the reasons for the failures of those who have returned from America is probably quite right. However, although I have taken account of your opinion, it has not influenced my understanding of the matter. Earlier, in my letter which I asked you to forward to Iyama Kentarô, I explained my reasons for my return and my situation upon that return and you must have read that. I think you will be aware that I have really taken your concerns into consideration.

I think that the business that I have in mind will require a capital outlay of about 10,000 yen. It is obvious that someone with my meagre resources will find it hard to turn such a business into reality. Still, within the limits of what I have seen and heard - at least in the states of California and Washington - I am confident that such a business has real prospects. I therefore judge that although it might not be easy to bring about, the chances of success are not hopeless, and this is why I have decided to return home. I mentioned in my last letter that the prospects for my plan will not become clear without my returning to Japan to investigate the situation on the ground. I am not therefore vainly and conceitedly overestimating my own ideas or thinking that I will easily and assuredly succeed.

If I may express myself frankly, there is not a huge difference in terms of advantages and disadvantages between the two alternatives of returning to Japan to set up in business and not succeeding, and remaining in America and simply seeing many years go by. From the outset, Japanese have had too many expectations of people who return from America. If the Japanese had looked on those who go to America as they do on country folk who move to Tokyo, then the circumstances of those who go to America would not have become as pitiable as they have today. Because the Japanese have had such great expectations of those returning from America, the latter have found it difficult to return home and end up just aimlessly idling away many years abroad. They steadily lose touch with the situation back home, and because the circumstances that would satisfy their will to set up in business do not exist in the place in which they are living, the end result is that they do nothing and just wile away the years. "I can't go back to Japan and I have no prospect of starting my own business in America even if I stay here, aah, what on earth shall I do?" I have often heard such sentiments from people who have been in this country for five or six years. It's no surprise that those who return to Japan oppressed by such feelings find it hard to prosper once they are back. Nevertheless, I feel it's better for such people to return and bear their shame for a while. In the future, what they have observed in this country can be of use. Their observations will be of use in Japan but not of much use elsewhere, so rather than remaining here for years to no avail, it is more worthwhile for them to return and put their experience to good use.....

In short, I don't have any great expectations of returnees. I hope people in Japan would not have any such great expectations for those who have come to America. I am sure you must be wondering why I am giving vent to such an eccentric opinion. Please allow me to explain something. From the outset, it was a mistake for Japanese to think that they could set up in business in America. The scale of that mistake is much greater than if they were to fail in business in Japan. For example, look at the cases where Japanese have started businesses in America. Not one has achieved good results. Not even people who have been living here for 10 or 20 years have been successful. The cases of Japanese capitalists who come to this country to start businesses normally end in failure. Why on earth is this? If they are failing despite having lived here for 10 or 20 years it can't be because there is something dark about the situation here. And when one looks at cases where such capitalists have failed, it's not because they have insufficient capital. So could it be, as is frequently said by Japanese living here, because Americans look upon Japanese as they do on Chinese and exclude them? That is certainly not the case.

As I see it, the real reason is something more desperate. It is the difference between the national character of the Japanese and the Americans. When the Japanese start in business, the sense of honor and decency that belongs to their national character is always present in the way they do things. Their way of starting a business is characterized by the broadmindedness of their planning and the small scale of their operations. If this is contrasted with the American way of starting a business, the difference is obvious. For Japanese to come to this country with these national traits and seek to confront the ferocious competition in this country should be described not as difficult but rather as impossible. Much more than Japanese, the Jews and Chinese here are subjected to great discrimination by Americans, and yet the Jews and Chinese all succeed in establishing themselves in business. If they did not display their national character in their business as much as the Americans, they would not be as successful as they are. So if Japanese are to succeed in starting up in business in this country, they must become familiar with the American national character. To do this, they need to have a wide range of contacts with Americans and they need to be prepared to suppress their original Japanese national character. If they suppress these Japanese characteristics, then they have a chance of success in business....

Reading this, one soon realizes that Fusatarô was keenly aware of how he was regarded by those around him. He points to the fact that the Japanese in America felt the pressure of the expectations of those back home and that resulted in people who wanted to return but felt that they could not. He avoided saying it directly, but in fact Fusatarô was obliquely criticizing the expectations which his own mother, his sister and her husband had of himself. He explains the difficulties of starting a business in America and speaks of the failure of returnees to profit from their experience in America by success in business back home. "I can't go back to Japan and I have no prospect of starting my own business in America even if I stay here, aah, what on earth shall I do?" - This was nothing other than the cry of Fusatarô's own heart.

And yet he is still only 21 years old; his is not a pessimistic character and he is earnestly seeking out the way to success in the world of business. In thinking about that, his research habits reappear, and he gives some serious thought to the reasons why Japanese in America are unable to achieve success in the American business world. He gives examples of Japanese who have lived in America for a long time or of wealthy Japanese capitalists who have all failed in business; he considers Jews and Chinese who succeed while yet being subjected to heavy discrimination; he contrasts these cases and seeks out the reasons why success eludes the Japanese. He then comes up with the answer - national character. The Japanese are affected by their values of honor and decency even in business, and these prove to be an obstacle to business. He concludes that to do business in America, Japanese have to give up being Japanese and become Americans.

He also criticizes the fact that Japanese business plans are bold but their actual scale is small. This observation is also rooted in his own failure. This is why, although he knows he does not have the financial resources, he conceives of a large plan and as part of his preparations decides on a trip to make a thorough investigation of mountain forest regions in Japan. Going into things in depth, gathering information and drawing up new plans on the basis of a thorough investigation of the situation before him - this is Fusatarô's way. These are excellent traits for a researcher but would they make a good businessman?

What emerges clearly from this letter is that at this time Fusatarô still saw success in business as his great aim in life. Academic studies of Takano Fusatarô have usually begun from the point where he became the pioneer of the Japanese labor union movement and have tended to relate his experiences in America to his connection with the labor movement. Certainly, by this time, in the year 1890, Takano had already become aware of the important role played by labor unions and had written a long article about the American labor movement for the Yomiruri Shimbun Newspaper. Just over six months later, he was to be at the center of the process that would lead to the founding of the Friends of Labor (Shokkô Giyuukai) but in the period before that, he was still tenaciously focused on his launch into a successful business career.

Another point that should not be overlooked is his insistence that "Japanese who have been abroad must make the most of what they have observed abroad after their return to Japan." They have had the chance to travel to an advanced country and see and hear what most Japanese had little chance to experience. They should therefore share what they have learned and experienced with their compatriots and put it to good use; otherwise, traveling abroad has no meaning. Fusatarô informed his compatriots of what he had learned of America's labor movement, and his becoming a labor leader himself was based precisely on these ideas of his.

Fusatarô the Swell

Fusatarô had returned to San Francisco to save money by learning the skills that would enable him to be a cook with good employment prospects, but at the same time, it was preparation just in case his business would fail. He intended to study English so that he would not be one about whom it would be said that "he's back from America yet he can't speak to foreigners" and judged that San Francisco, where there were schools that required no fees, would be a good place to study. One sees how far he was thinking ahead but at the same time, one cannot but get the impression that he was rather too conscious of what others thought of him. From various other episodes too it is clear that Takano Fusatarô was something of a show-off. This was not just his own character, but a common tendency among the people of his hometown of Nagasaki. Yoshimura Kunio, the Nagasaki local historian, has written that "there were many in Nagasaki who were elegant, magnanimous, not obstinate and were show-offs." and this description also fits Takano Fusatarô to a tee. But this concern for reputation was what provided him with the motive and the resolve to learn English, and he was prepared to endure poverty to do so. One should not overlook the fact that such a concern for one's reputation can also have its plus side.

Arriving back in San Francisco driven by this impulse, Fusatarô repeatedly tried to assure his family in letters "not to worry because I'm acting only after careful investigation and serious thought", but he made an uncharacteristic mistake: the Commercial High School did not accept mid-term enrolments. He would not be able to go to school until January and would have to work for three months. But unlike Tacoma, there were no good jobs to be had, and he ended up asking his former employers, the Brayton family, for work.

A week after he began his studies, Fusatarô wrote to his brother in the evening of January 9, 1891 to tell him about his experience studying at school in America. It was a postcard, but the writing was very small, so the contents are quite detailed.

I've been fine since I last wrote so please don't worry about me. On the 2nd I quit working for my former family and on the 4th started classes. But there aren't enough schoolboy jobs, and I'm already having real difficulties. I haven't been working for a week, so from the money I made working for the family, I sent $10 to you at home and spent $11 on books, which has left me with just $6 or 7, which will be used up today or tomorrow. But tomorrow and the day after, there is no school, so I'll be able to work for my former employers and elsewhere and make about $2. Once I've established where I'll be working, I'll ask my friends in Tacoma for a loan and send you a remittance.

The subjects at school are quite difficult. Book-keeping, commercial law, commercial geography, civics, calligraphy, "The Lady of the Lake", arithmetic, composition, business letter writing, Spanish - they all require homework and I do about 3 or 4 hours after school every day...

The San Francisco Commercial High School was a secondary school-level institute run by the city and took no tuition fees. It had a three year full-time course and a one year limited course; Fusatarô enrolled in the latter. There were 400 students in total in both courses and a gender ratio of two men to one woman. There were 16 teachers including the principal, of whom 8 were women. Fusatarô's aim in enrolling was to learn English properly and to be able to express himself freely in conversation with foreigners. Surrounded by classmates who did not understand Japanese and with all his lessons conducted only in English, Fusatarô's listening and speaking skills must have improved considerably.

In the important English lessons the focus was Walter Scott's epic poem The Lady of the Lake. This had been the basis for songs by Schubert and an opera by Rossini, so at the time it was a work that was widely read around the world. Apart from the book-keeping class, all classes and the homework for them - which lasted just as long - were compulsory.

Two months after starting his classes at the Commercial High School, Fusatarô wrote as follows in a letter of March 10, 1891:

I got the date of the last mail-boat wrong so I missed the post. The enclosed postal order is the remittance for last month. I'm very sorry it's late. I think I'll manage to send this month's remittance before the end of the month. I'm going to school every day. I've already received two monthly report cards, and the results have been fairly good. Report cards are handed out at the end of every month at schools here to inform students' parents of their results in all subjects. Students have to show this to their parents, get their signature and return the report to the school. None of the subjects are especially difficult, but I find the grammar and interpretation of The Lady of the Lake really hard. These days everything's going just fine. On evenings when it doesn't interfere with my studies, I work as a waiter in a newly opened Japanese restaurant from 7 until 12. Unlike when I was a schoolboy, even after I've taken out of my wages the money to send back home to you, there's still some left over. But I don't know how secure this job is. Recently, when I was unemployed for a month, in a boarding house run by a Japanese I was studying in poor light and my eyesight suffered, so I couldn't do the shorthand class. After I started working at a restaurant in the evenings, my eyesight got better, but when you have time, could you buy two or three bottles of seikisui and send it to me? It's to help me make sure I don't mess up again and damage my eyesight.....

As this letter makes clear, Fusatarô was not putting all his energies into his studies at the Commercial High School. On top of having to support himself, he was obliged to send money home. He was unemployed for a month, worked as a school boy, as a waiter in a Japanese restaurant and as an interpreter at an immigration office - he was doing one job after another. His worsening eyesight was one more bitter pill to swallow in addition to the daily poverty of his hard life.

The seikisui referred to was an eye medicine produced and sold by Kishida Ginko. The formula of the medicine was the idea of James Hepburn, famous for devising a method of romanizing Japanese and Chinese. Ginko had worked for Hepburn in compiling Japanese-English Dictionary (Wa-Eigo rin shusei) and had secured the rights from Hepburn to produce the medicine. A painter Kishida Ryûsei, well-known for his Portrait of Reiko was Ginko's fourth son.

Let us turn to another letter which describes Fusatarô's hard life in America as well as that of his mother and brother in Tokyo, who were struggling with financial problems and a burden of debt.

I enclose a postal order for $12. I had wanted to send a bit more for father's memorial service but I am under quite some pressure at present, so please accept this amount together with my sincere apologies. As far as my interpreting job at the immigration office goes, last month a manager was made redundant, so I was laid off. I have been casting about since then looking for work, but nothing suitable has come up, and I'm in some difficulties. At the moment, I'm working here at the Cosmopolitan Hotel. The job is quite simple: three times a month I have to go to the harbor when the passenger boats arrive from Japan and bring the passengers for the hotel here. Meals and accommodation are provided but no wages. But I have a friend of mine eat here instead of me and he gives me $10 a month, which I send to you. I eat elsewhere, which costs just over $7.

I have to earn that amount somehow and until today I've been managing on what was left of the money I made interpreting at the immigration office. I've used all that up now, and I'm looking for another suitable job, but I haven't found anything as yet. Incidentally (this is only for you, brother, so please say nothing of this to mother; she would only worry) for the last three months I felt my eyesight was getting worse and on the 13th, after I got back from the country, the pain got much worse, so I consulted a doctor, and since then I've been going to the hospital every day. I have to go for another week. As a result, there is now a large imbalance between my income and my expenditure. I've asked a friend in Tacoma to lend me some money, and if this just works out then I should be able to pay for the medicines, and then I think all will turn out well. The worst of it is that the doctor has forbidden me to read at night, but he said I could go to school during the day, so I'm still going. My eyes have got much better in the last one or two days. In three or four more days I'm sure I'll be back to normal again, so please don't worry yourself. But somehow I have to pay the doctor's bill.

So, until my next letter, I would ask you to defer the monthly payments to Sakanaya in Naniwachô. I'm sure it'll work out with the loan from my friend, but it may be that next month's remittance will be affected by these circumstances. I hope I'll be able to clear everything up in my next letter, but until then, please defer the payment. And please do not worry yourself about my eyesight problem. I am doing well at school and I will be allowed to move up to the next level along with my classmates, of whom there are over 10. I will finally graduate in December, so don't worry yourself.

Please figure out, and let me know, how much you need to pay back the present loan in monthly instalments until December and how much of the loan will be outstanding by the end of the year. I will need to know this as it will affect prospects for the future.

Surrounded by these difficulties, Fusatarô continued to apply himself earnestly to his studies and achieved very good results. His letter of October 20, 1891 included copies of his school report cards from July to September. In arithmetic, commercial law, English business letter writing his grade was 'excellent'; in accounting and Spanish - good; in English and type-writing, it was satisfactory. His grades for 'conduct' are noteworthy: in the five areas, which included deportment, good order, and observance of school regulations, his grades were all 'excellent'. He was regarded as a diligent and hard-working student.

The riddle of the founding year of the Friends of Labor

The period Fusatarô spent at the San Francisco Commercial High School was one in which he was very hard-pressed in terms of both time and money. His time was taken up not only by his studies at school but by the preparation and homework he had to do at home. He had to work until late at night to make the money he needed to remit to his family and at weekends he had to do side jobs. Yet it was during this extremely trying period that the event occurred which was to be the turning point in his life: the founding of the Friends of Labor (Shokkô Giyûkai). This group gave birth to what in later years was Japan's first modern labor movement organization, Rôdô kumiai kiseikai (the Association for Encouragement and Formation of Trades Unions). More accurately, the members of The Friends of Labor returned to Japan and reformed the group in Tokyo, where it became the central focus of what then organized itself as the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions. In other words, the Friends of Labor in San Francisco were the original source of the group that then originated Japan's labor union movement: this was Takano Fusataro's starting point as a labor movement activist.

In fact, the date given for the founding of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco has been mistaken for a long time, and this is why some scholars have insisted that Takano Fusatarô was not present at the founding meeting of the Friends of Labor and was not a key member of the group. Evidence for this was held to be the Rôdô kumiai kiseikai seiritsu oyobi hattatsu no reikishi (The founding and development of the Association for Encouragement and Formation of Trades Unions), a series of articles in Rôdô Sekai (Labor World). The relevant passage is the following - or rather, what follows is an account of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco.

At the time of chûka (midsummer) in 1890, a group then living in San Francisco, USA, which consisted of Jô Tsunetarô, Sawada Han'nosuke, Hirano Eitaroo, Takano Fusatarô and two or three others, assembled and founded the Friends of Labor. Their aim was to study the current situation obtaining in Europe and America with regard to labor issues and apply what they had learned to the interpretation of labor issues in Japan.

This passage is cited word for word in Nihon no rôdô undô (The Japanese Labor Movement), a classic work of the Japanese labor movement by Katayama Sen and Nishikawa Mitsujirô. If the Friends of Labor was founded in San Francisco in the summer of 1890, then Fusatarô was in Tacoma, so Takano could not have been present at the founding meeting. Then, Takano Fusatarô must have joined in only after the founding and could not therefore have been a key member. Those supposition was insisted by Sumiya Mikio, a notable labor economist and historian, and people believed it for years.

I doubted this argument. If one reads the actual extant historical documents, then it is clear that Takano was present at the founding meeting. Furthermore, among Japanese at that time, Takano was the first to show a real interest in the labor movement and had the deepest knowledge of it. There was something wrong with the argument that he had not been present at the founding and that he was not a key member. I felt there must be a mistake in the sources.

After carrying out various researches, I discovered that, assuming that the date of summer 1890 is correct, Sawada Han'nosuke had not yet traveled to America. I found it from the record of issuing passport of Sawada Han'nosuke that he could only have traveled to America after the end of 1890.

Meanwhile, it has been overlooked that there is another source that mentions the founding of the Friends of Labor. The Keisei Shinpô (Governing Nation News), published in Tokyo October 16, 1891, carried an article titled 'Beikoku sôkô ni waga rôdô giyûkai okoru' (Founding of the Japanese Friends of Labor in San Francisco, America).

Resident in San Francisco, USA for some time and currently working in the city as shoemakers, Jô Tsunetarô and Hirano Eitarô, not in the least daunted by the parlous state of labor associations in Japan, and seeing the situation getting ever worse, having gathered a number of opinions, sent word to a number of friends at home to persuade them of the advantages in establishing labor unions, to set up groups of craftsmen's unions in different regions, establish a central office to administer the groups nationwide as well as regional offices and in order to overcome the obstacles which have obstructed labor unions heretofore, to increase their advantages and by this means to further mutual aid and alleviate the situation of labor associations in Japan. The two men have therefore stepped forward at 1108 Mission Street, San Francisco with the aim of improving the state of labor associations and have appealed to Japanese living in San Francisco to share their joys and sorrows. Members meet every first and third Saturday in the month. Their numbers are currently increasing rapidly and have earned the respect of the local population.

From this article the Friends of Labor can be seen to have had the practical aim of getting friends to work towards the formation of labor unions.

The problem is the date of the founding. That a newspaper would print news of an event that had happened over a year earlier about "the two men stepping forward" with no apology or further comment suggests that the report regarded the founding date of 1891 as a fact. So which date is one to trust: the 1890 date given in "The Founding and Development of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions", or the 1891 date in this newspaper report? "The Founding and Development" was written by the people involved and based on contemporary records but was actually penned seven or eight years after the event. By contrast, the newspaper report in Keisei Shinpô appeared at the time of the event. Clearly, the newspaper report would seem to have more credibility as a record of the date of the founding.

On the other hand, while no name was appended to "The Founding and Development" articles, the author was in fact Takano Fusatarô. One sees no-one else who would have been able to record the period of the movement from Shokkô Giyûkai to Kiseikai, and when one runs through the lists of names, the name Takano Fusatarô always appears last - this would seem to the most tangible evidence.

However, from other sources, it is clear that Takano was not good at calculating dates (distinguishing the western and Japanese calendars). To give an example, in one of his English language articles, he gives the date of the 1891 (Meiji 24) stonemasons' strike in Tokyo as 1890. A similar error must have occurred when he gave the date of the founding of the Shokkô Giyûkai as 1890 (Meiji 23). Instead of rendering 1891 as Meiji 24, as he should have done, he mistakenly rendered it as Meiji 23. With this in mind, we are for the first time able to make the previously cited passage conform to the historical facts.

If it was 1891, then 'chûka' (midsummer) would have been the period from June 7 to July 5; because the word 'chûka' meant 'fifth month in the lunar calendar'. Then the school was on summer holiday - from May 22 to July 21-, so even Fusatarô, who had been harassed by his studies and side jobs, would have had time free to devote to the founding of the Shokkô Giyûkai. In the summer of 1891 Sawada Han'nosuke had already arrived in America and so would have had no problem attending the founding meeting. On the basis of these various points, we can safely state that the founding of Shokkô Giyûkai (The Friends of Labor) in San Francisco occurred in 1891. The season was early summer, and as the Giyûkai meetings took place on the first and third Saturdays of the month, we can assume that the founding meeting must have been held on either June 20 or July 4, 1891. I would suppose that the day was the latter, because it was the Independence Day.

The Friends of Labor Threesome

We shall now look a little more closely at the two other key founding members of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco - Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke.

We shall now look a little more closely at the two other key founding members of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco - Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke.

Jô Tsunetarô was born in Kumamoto on April 21, 1863 and was five years older than Takano. He had a difficult childhood: his father died when he was very young, his family was caught up in the Seinan War in 1877, his home was burnt out and the family split up. While working at the Kumamoto branch of the Yorita Nishimura gumi as an office boy, he was discovered by Nishimura Katsuzô, who had come to inspect the branch and he became a pupil at Ise-katsu shoemaking workshop in Kôbe. Having learned the craft of making shoes, he opened his own shop in Nagasaki. He got to know from a short report in the Kokumin no tomo (The Nation's Friend) Magazine of the summer of 1888 that there were many Chinese shoemakers working in San Francisco, and in order to plough a new furrow for Japanese shoemakers, that same year he headed off alone to America. Jô's mentor, Nishimura Katsuzô, a major figure in Japanese shoemaking, admired his pioneering spirit and achievement so much that he had a monument erected in Jô's honor and composed the text for it himself. It includes following passage:

Jô Tsunetarô was quiet and hardly moved by natre, was intelligent and quick-thinking, deplored the situation in which Japanese shoemakers found themselves and worked earnestly to improve it. In August 1888, using his own savings, he sailed to San Francisco where, after first working at a hotel, he rented a basement room and opened a shoemaker's shop.

After returning to Japan, Jô, together with Takano and Sawada, reorganized the Friends of Labor in Tokyo and promoted it from his own home, which he provided as the office for the organization. He damaged his health and had to step back from the frontline of the movement's activities, but his relationship with Takano continued. When Takano went to China in the summer of 1900, Jô intended to go with him and set up an enterprise there together, but his wife was pregnant, so Jô delayed his departure. When he arrived in Tianjin, Takano had already left the area. Jô then set about creating a lemonade making business there, which is said to have been a success, but after a few years entrusted it to his brother and returned to Japan. He soon came down again with chronic tuberculosis and just over a year after the death of Takano, died on July 26, 1905 in Ôsaka at the age of 42.

Sawada Han'nosuke was born in September 1869, the same year as Takano, in Sukagawa, Iwase County, Fukushima Prefecture. The Japanese language newspaper reporter Washizu Shakuma, appended to his book Zaibei nihonjin shikan (A History of Japanese in America) a section on 'The Pioneers of various Japanese trades in America' and cites Sawada as the founder of Japanese tailoring businesses there. The full text on his part is as follows:

Sawada traveled to America in 1890 and the following year moved into Jô's shoe repair shop at the corner of Mission St and 7th St., where he started his own tailoring business. This was to become the pioneering tailoring business run by Japanese in the United States. It is noteworthy that unlike today, tailors' shops of western-style clothes and shoe repairers' shops were often very poverty-stricken, and the shop at which Jô and Sawada shared the $15 rent was at a location where there were few passers-by. There they plied their trades as tailor and shoe repairer, but their situation was a miserable one. At that time the almost all Japanese in America were bachelors; they would sleep on self-made beds at the back of shops. The Jô and Sawada's shop were also one room, and it served not only as a shop, but also kitchen, bedroom, parlor and dining room. Their meals consisted of bread, coffee and wheat flour dumpling soup. But when they had few customers, they barely eat, often no more than one meal a day.

Sawada's 'tailoring' business amounted to little more than the name, as most of the work available was in laundering and repairing, rather than actual tailoring. In the early days of the business he had no new tailoring orders. There were five to six thousand Japanese in San Francisco at that time, but most of them were of 'schoolboy' status; they earned no more than 50 cents to $1 a week, so were in no position to place orders for new clothes. Most of them were given cast-offs by their employers, and if they really had to buy new clothes, they would have to make do with going to the second-hand shop on Howard Street and buying a suit for $3 or a pair of second-hand shoes for 50 cents.

The shop jointly rented by Jô and Sawada at Mission Street was the office of the Shokkô Giyûkai. An advertisement for the Sawada Saihôjo (tailoring shop) placed in San Francisco's Japanese language newspaper Ensei (Expedition), gave 1108 Mission Street as the address, the exactly the same address in The Keisei Shinpô's article on the Rôdô Giyûkai.

On his return to Japan, Sawada Han'nosuke also took part in the reconstructing of Shokkô Giyûkai, and along with Takano and Katayama Sen, was chosen as an official of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions and spoke at many public lecture meetings. He started a tailoring business on Ginza's Owarichô, and after the collapse of the Kiseikai, he left the labor movement, participated in the establishment of a uniform-making factory at Ôi for the Ministry of Railways, set up the Beiyû Kyôkai (Japan-America Friendship Society) with Kaneko Kentarô, promoted the erection of a commemorative monument to Townshend Harris in Kurihama, Kanagawa Prefecture, and became a major figure in the tailoring business and in promoting Japanese-American relations. Of the three founders of the Shokkô Giyûkai, he was the one who achieved worldly success. He died on June 17, 1934, aged 65.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), Chapter 5 Shokkô giyûkai wo soritsu

|

The book deals with the various labor and social problems America was facing in that period, with a focus on the workers' movement, and mostly written by contemporary labor leaders. There seems little reason to doubt that Fusatarô gained a comprehensive understanding of the labor movement from this book. Incidentally the Internet Archives has made

The book deals with the various labor and social problems America was facing in that period, with a focus on the workers' movement, and mostly written by contemporary labor leaders. There seems little reason to doubt that Fusatarô gained a comprehensive understanding of the labor movement from this book. Incidentally the Internet Archives has made  From the age of the two boys, it is supposed that this was taken at the time of Fusatarô's higher elementary school graduation, that is, just after the time when, according to Iwasaburô's memoirs, the Nagasakiya was burned down in the great fire, and the family were

From the age of the two boys, it is supposed that this was taken at the time of Fusatarô's higher elementary school graduation, that is, just after the time when, according to Iwasaburô's memoirs, the Nagasakiya was burned down in the great fire, and the family were  They were known for their tactic of sticking a 'union label' on shoes that had been made by white shoemakers and calling for boycotts of products made by non-union [i.e. non-white] labor. Such unions would certainly have been a topic of conversation between the shoemaker Jô and Takano. Proof exists in fact that more than anything, it was the American shoemakers' campaign to exclude Chinese labor that first made Takano aware of the power of labor unions. His first report about the American labor movement, titled 'Hokubei gasshûkoku no rôeki-shakai no arisama wo josu' (A View on Labor Societies in the United States of America) begins as follows:

They were known for their tactic of sticking a 'union label' on shoes that had been made by white shoemakers and calling for boycotts of products made by non-union [i.e. non-white] labor. Such unions would certainly have been a topic of conversation between the shoemaker Jô and Takano. Proof exists in fact that more than anything, it was the American shoemakers' campaign to exclude Chinese labor that first made Takano aware of the power of labor unions. His first report about the American labor movement, titled 'Hokubei gasshûkoku no rôeki-shakai no arisama wo josu' (A View on Labor Societies in the United States of America) begins as follows:  There is a colorful little essay that describes summer in Tacoma and gives us an impression of what the town of Tacoma was like at that time. As it was written in the year before Fusatarô moved to Tacoma, it presents us with a picture of the town that he saw.

There is a colorful little essay that describes summer in Tacoma and gives us an impression of what the town of Tacoma was like at that time. As it was written in the year before Fusatarô moved to Tacoma, it presents us with a picture of the town that he saw.

Pacific Avenue was Tacoma's only main thoroughfare; photographs of the period show a row of three-story stone buildings with tramcars running along the street. With a rent of $200 and 10 staff, it would have been a large restaurant.

Pacific Avenue was Tacoma's only main thoroughfare; photographs of the period show a row of three-story stone buildings with tramcars running along the street. With a rent of $200 and 10 staff, it would have been a large restaurant.

Until now the story has many times been hampered by a lack of source documents, but from here onwards the situation changes. 26 letters and postcards addressed to his brother survive from the period of just over two years from August 1890 to September 1892, and they inform us in quite some detail as to his situation: not only what he did and when, but also what he was thinking in those situations and what hopes and desires he was harboring. Generally speaking, Fusatarô's writings in Japanese tend not to reveal his feelings, but this particular batch of correspondence is rather different in this respect; it includes some very direct expressions of what he was feeling. Thus far, I have avoided lengthy quotations from source documents, but this correspondence requires rather more detailed citation because it reveals to us something of the man's heart and soul. First, a letter of October 9, 1890:

Until now the story has many times been hampered by a lack of source documents, but from here onwards the situation changes. 26 letters and postcards addressed to his brother survive from the period of just over two years from August 1890 to September 1892, and they inform us in quite some detail as to his situation: not only what he did and when, but also what he was thinking in those situations and what hopes and desires he was harboring. Generally speaking, Fusatarô's writings in Japanese tend not to reveal his feelings, but this particular batch of correspondence is rather different in this respect; it includes some very direct expressions of what he was feeling. Thus far, I have avoided lengthy quotations from source documents, but this correspondence requires rather more detailed citation because it reveals to us something of the man's heart and soul. First, a letter of October 9, 1890:

We shall now look a little more closely at the two other key founding members of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco - Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke.

We shall now look a little more closely at the two other key founding members of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco - Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke.