Chapter 13 The Decline of the Ironworkers' Union

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | Union Income | Paying Amount | Balance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of paying members | Amount paid | Head office costs | Relief | Total | ||

| 1897.12 - 98.2 | 1,288 | 772.80 | 461.60 | - | 461.60 | 311.20 |

| 1898. 3 - 98.5 | 1,030 | 985.40 | 560.57 | 134.20 | 694.77 | 290.63 |

| 1898.9 - 98.11 | 1,497 | 898.40 | 531.38 | 299.00 | 830.38 | 68.02 |

| 1899. 3 - 99.5 | 1,690 | 1,019.00 | 878.82 | 400.25 | 1,279.07 | -260.07 |

| 1899. 6 - 99.8 | 2,092 | 1,255.00 | 884.50 | 684.40 | 1,568.90 | -313.90 |

| 1899. 9 - 99.11 | 1,831 | 1,098.60 | 487.69 | 832.25 | 1,319.94 | -221.34 |

| 1899.11 - 00.2 | 925 | 554.80 | 425.88 | 123.43 | 549.31 | 5.49 |

But in expenditures, relief and support costs to members continued to rise steadily, leading to a series of substantial deficits. As a result, at the general meeting of the Union's head office committee on October 8, reductions in payments of relief were decided on as follows:

1. The payment of relief per day to be reduced from 20 sen per day to 15 sen and the date of commencement of payments of relief to sick members to be extended from 21 days from the start of the illness to 30 days.

2. Funeral costs to be cut from 20 yen to 15 yen and the applicability threshold for funeral aid payments to be raised from 6 months' membership to one year's membership.

3. Members whose families have suffered bereavement to have their allowances cut from 10 yen to 5 yen and the applicability of payment to be raised from one year's membership to two years' membership.

However, these radical money-saving policies - reductions in relief payments and the reduction in the free delivery of The Labor World from twice to once - had no effect; on the contrary, they only served to reduce the energy of the Union still further. An especially severe problem was the drastic decline in the number of dues-paying members: 1,544, the highest number ever recorded, for the following month of October 1,899, dropped suddenly to 1,509 in November and then 942 in December.

What accounted for this drastic fall-off in the number of members paying their dues? One theory focuses on the cut in relief imposed in October. This measure had the effect of depressing the members' spirits and led to many workers quitting the Union. The fall in the number of members paying their dues immediately after the reduction in relief payments indicates the possibility that some members were angered by the reduction and left the Union, or that they cut the amount of the dues they paid. But it is doubtful that this was the main reason for the drastic drop in members paying their dues. Putting oneself in the position of workers who had joined the Union because they were attracted by the offer of relief payments, those payments had not been completely terminated but only reduced, and it is hard to imagine that they would suddenly quit the Union and opt to thow away the right to receive the relief payments that they had acquired.

Dismissals of the arsenal workers - 'exemplary punishment'

In fact, the reason for the sudden fall-off in membership at the Ironworkers' Union lies elsewhere. At the Tokyo Arsenal, the main organizational base of the Union's membership, there were increasing moves to force workers to quit the Union, and activists were being sacked to set an example. The Labor World was apt to overlook such incidents, avoiding reporting on them as it feared the impact such reports would have on Union members. However, the Mainichi Newspaper on December 2, 1899 carried the following report:

Mamie Kintarô, Takahashi Sadakichi and others who were enthusiastic activists for the Rôdô Kumiai Kiseikai organization were sacked from their jobs at the Tokyo Arsenal for no obvious reason whatsoever.

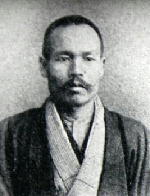

Mamie Kintarô, who had been laid off, had occupied a number of official posts in the movement: he had been a member of Kiseikai's standing committee since its founding,  a founding member of the Ironworkers' Union, the No. 10 Branch delegate to head office committee meetings and was the deputy general manager at the Union's head office.

In September 1899 there were 161 dues-paying members at the No. 10 Branch to which he belonged, but this number fell to 60 in October, 43 in November, and 22 in December. From January 1900 onwards, it was zero. There can be little doubt that this decline reflected the pressure exerted by the Arsenal management as exemplified by Mamie's dismissal.

a founding member of the Ironworkers' Union, the No. 10 Branch delegate to head office committee meetings and was the deputy general manager at the Union's head office.

In September 1899 there were 161 dues-paying members at the No. 10 Branch to which he belonged, but this number fell to 60 in October, 43 in November, and 22 in December. From January 1900 onwards, it was zero. There can be little doubt that this decline reflected the pressure exerted by the Arsenal management as exemplified by Mamie's dismissal.

Like Mamie, Takahashi Sadakichi had been a zealous activist since the founding of Kiseikai, a founding committee member of the Ironworkers' Union, the No. 5 Branch elected delegate to head office committee meetings and a member of the Kiseikai special campaigns committee; he had also been active as an advocate for workers at public meetings up and down the country. In September there were 50 dues-paying members of the Union in his No.5 Branch, 23 in October, 21 in November, 15 in December, 11 in January and zero in February - a similar pattern to that in No. 10 Branch. This is probably to be seen as reflecting the same direct impact of the dismissals of Takahashi and the others. The Mainichi Newspaper report of the dismissals refers to "Takahashi and others", so others seem to have been sacked with him.

a founding committee member of the Ironworkers' Union, the No. 5 Branch elected delegate to head office committee meetings and a member of the Kiseikai special campaigns committee; he had also been active as an advocate for workers at public meetings up and down the country. In September there were 50 dues-paying members of the Union in his No.5 Branch, 23 in October, 21 in November, 15 in December, 11 in January and zero in February - a similar pattern to that in No. 10 Branch. This is probably to be seen as reflecting the same direct impact of the dismissals of Takahashi and the others. The Mainichi Newspaper report of the dismissals refers to "Takahashi and others", so others seem to have been sacked with him.

It thus seems that from the autumn of 1899 a new hardline policy was implemented at the Tokyo Arsenal with regard to the Ironworkers' Union and that the effect of the subsequent dismissals spread through the Union membership. Even without reports in the official Union media, workers soon got to hear of such incidents. The fact that important events such as the sackings of Union officials could not be reported in The Labor World itself shows the weakness of the organizational strength of the branches at the Tokyo Arsenal. Defending the sacked activists in the name of the union movement was the most important duty of a labor union, but the Union members at the Arsenal were unable to take such action and quit the Union. This also suggests that while Mamie and Takahashi had been conspicuously active outside the Arsenal Branches, at their workplaces they had been unable to gain the support of their comrades. From the beginning, the Ironworkers' Union had grown steadily at the Arsenal because the technical engineers there had been present at the Union's founding ceremony, had shown understanding for the union movement and also because Muramatsu Tamitarô had advocated organizing unions around senior, experienced workers. The engineers had shown this understanding for the Union because Kiseikai and the Union had consistently followed a moderate line, had an understanding of factories in the West and did not have such a hostile attitude towards labor unions.

However, from the autumn of 1899, the situation took a rapid turn. It is not known whether the new direction resulted from orders from senior army commanders or from a change of policy at the Tokyo Arsenal, but at some level or other, the policy towards the Ironworkers' Union clearly changed. It is likely that in the course of the discussions in the Diet in early 1900 of the Public Order and Police Law, the following concerns of officials at the Ministry of Home affairs were communicated by some route to the authorities at the Tokyo Arsenal as the reason for the Bill:

Above all, if producers who supply military materiel were suddenly to be affected by strike actions, it would have no small effect on the capacity to wage war. For example, if workers at the Arsenal were to go on strike during a war, our nation's military would be placed in an exceedingly disadvantageous situation.

When the outer circumstances changed in this way, the union organization that had proceeded under the favorable conditions of the engineers' support quickly began to collapse.

Among those companies and enterprises which the Ironworkers' Union saw as the organizational basis of its activities there were, of course, from the time of the founding of the Union those which had an antagonistic attitude towards the Union. For example, immediately after the Union was founded, the Yokohama Shipping Company put pressure on foreman Hirai Umegorô, who had been appointed General Manager at the Union's head office, and forced him to quit the Union. The early collapses of the the Union branches at the Shinbashi Factory of JNR and the Kôbu Railway Company were most likely due to pressure applied by the managements of those railroad companies after they had seen and heard about the Japan Railway Company locomotive drivers' strike and became apprehensive about labor unions. The Japan Railway Company itself, which had experienced the strike, was wary of the Ironworkers' Union early on. Not only many of the top mangement but also many among the foremen and shop floor senior workers made no attempt to disguise their open hostility towards unions. The Union members at the company went on steadily with their efforts to organize in these difficult circumstances, and compared to branches at other companies, created a solid organization. The Labor World was quick to report frankly on the Japan Railway management's hostile policy towards the Union, and its critiques pointed up the strength of the Union branches at the company. For example, soon after the founding of the Union, the following report appeared:

Difficulties at the Ômiya Works

The Ironworkers' Union movement at Ômiya is currently encountering a number of difficulties. These are all due to problems occurring with the onsite technicians at the Ômiya Works, some of whom think that workers engaged in labor union campaigning ought to be sacked or else they summon the men's workgang leaders and make emotional appeals to them not to forget their obligations to the shareholders by getting involved with the union. Or else, they say that the Union is alright but that the workers should withdraw from it for a while, or else that workers who end their connection to the Union will get a pay rise. By resorting to all kinds of low tactics such as these, they are trying in innumerable ways to block the Ironworkers' Union movement....

Despite these company tactics, the Union managed to set up a number of branches within the Japan Railway Company: No. 2 Branch (Ômiya), No. 23 Branch (Fukushima), No. 26 Branch (Morioka), No. 39 Branch (Ômiya Carpenters), No. 40 Branch (Mito) and succeeded in extending the organization in an atmosphere of conflict and tension with their foremen and supervisers. Of the more than 1,300 workers who were working at a number of large sites in the Kantô area in 1897, at the Ômiya Works, the number of Ironworkers' Union branch members was of the level of 150-200, the highest in the Union.

At any rate, it is worth noting that the Union branches were able to maintain and extend their organizational effectiveness at a company that was pursuing a suppressive policy against unions. That locomotive engineers at this company were able to take strike action and secure improvements in their working conditions and were then able to establish The Japan Railway's Society to Correct Abuses (Nittetsu Kyoseikai), which was even called "a model organization of a militant labor union", and then even went on to succeed in getting the sacked strike leaders reinstated testified to the strength of the Union branches at the company.

However, even at the Japan Railway Ômiya Works there were dismissals of Union members in November 1899. A Union member was sacked after he had criticized a foreman's petty despotism at the foundry at the Ômiya Works. The Ironworkers' Union No. 2 Branch openly began to organize a campaign in support of the sacked man, and Katayama Sen and others lent their support to the campaign. They called on the President of Japan Railway to remonstrate with him, and claiming the role of 'mediators', sought to persuade him to reinstate the sacked worker. The Union introduced a special 5 sen per member levy and held a number of public meetings at Ômiya. This time, unlike the case of the sackings at the Arsenal, The Labor World reported on the case with a critical piece entitled "Rottenness at Japan Railway Ômiya Works". Eventually however, the dismissal was not revoked. This proved to be a turning point and thereafter, the No.2 Branch at Ômiya, which had been the most energetic Union branch, fell under increasing pressure.

It is my view that the main reason for the rapid decline in the fortunes of the Ironworkers' Union from the autumn of 1899 onwards was due to the increasing severity of employers' attacks on the Union. Another factor in the decline which cannot be overlooked is that the ordinary members did not have a really strong consciousness of belonging to the Union. We shall cite here again a passage already quoted from Katayama and Nishikawa's The Labor Movement in Japan where they explain the reasons for the decline of Kiseikai in 1900:

When union members who had joined the union without actually understanding what the labor movement really meant, simply because they had been attracted during the boom years of the movement, and later quit one after the other, and a leading member put his own livelihood first and were not necessarily able to devote himself wholeheartedly to Kiseikai.

In other words, there were among the membership those who had 'simply joined during the boom years of the movement' and who then 'quit one after the other' when things became more difficult. Without a sufficient understanding of the labor union movement, they joined the movement because their mates had joined and then soon quit afterwards. As we shall see later, the proposal to raise the union dues by 2 sen to try to address the Union's financial difficulties did not become a contentious issue and was rejected without any fuss; this too was doubtless a reflection of the same background factor of the members' weak motivation and consciousness of what it meant to belong to a union.

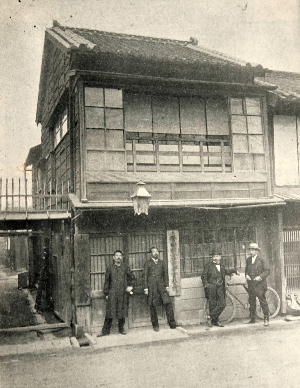

The cooperative store at Hatchôbori

The Union's worsening financial situation directly impacted on Fusatarô's livelihood, as he was a paid employee. It meant that salary payments might well be delayed. It is likely that in order to cope with this situation, Fusatarô moved to Hatchôbori and started a cooperative business. From the following report in The Labor World of November 1, 1899 it would appear that the store must have been opened in October.

Mr Takano Fusatarô Mr Takano has moved to 2-4, Hatchôbori, Kyôbashi Ward.

This was not just a notification of a change of address; the reason for the move was given in the English language column of the same issue of the newspaper:

Mr F. Takano today opened a general store which distributes profit to the patrons by means of a partial application of the Lodgedale (sic.) [Rochdale] method.

The cooperative store was aimed at serving the Ironworkers' Union members who were employed at the Ishikawajima Shipyard and at the Oki Electrical Works (later Oki Electrics). This is clear from subsequent short reports and notices in The Labor World.

Only a short time has passed since the opening of Mr Takano's cooperative store, but the venture is reported to be doing extremely well, and the store now apparently also has patrons in Urawa. Mr Takano's attention to detail and his enthusiasm are certain to bring his venture trust and profit. We trust that his store will enjoy the success it deserves as the first real profit-sharing store. (Issue No. 50)

A clubhouse for workers at Ishikawajima has been set up on the second story of the cooperative and is splendidly well fitted out. (Issue No. 51)

I would like to thank you most warmly for your kindness at the time of establishment of the cooperative store. I ought to have offered my thanks in person but I have been so busy at the store that I have had to take the oppotunity of offering my gratitude in the form of this notice.

Takano Fusatarô The Cooperative Company (Kyôeisha)

2-4 Hatchôbori, Kyôbashi ward, Tokyo

To the workers at Ishikawajima Shipyard and Oki Electrical Works (notice in Issue No. 51)

There were five branches of the Ironworkers' Union at the Ishikawajima Shipyard: No.16, No. 20, No. 21, No. 31, and No. 32. At the shipyard effective power was in the hands of the labor gang boss Ozawa Benzô, who was also a leading union activist, and this was a great advantage for the Union which it did not enjoy at other companies.

At the end of the Tokugawa period (late 1860s) Ozawa Benzô had moved from being a blacksmith to an ironworker, one of Japan's first of the new 'western-style metalworkers'; he had many workers under his command and at the Ishikawajima Shipyard he had the role of overseer of the workforce. Ten years before the establishment of the Ironworkers' Union, with his brother Kunitarô and others he was a pioneer of the ironworkers' movement who had planned the formation of an ironworkers' union. At the time their efforts were not successful, but in 1889 he was the leading figure in a combination of ironworkers from theTokyo Army Arsenal and the Tanaka Mechanical Engineering Works who formed an organisation called the Dômei Shinkôgumi (Workers' League for Union and Progress). The Dômei Shinkôgumi introduced new workers to companies, mediated between labor and management at times of dispute, set up a workshop aimed at teaching workers technical skills. It was a group that deserves to be called a forerunner of the type of organization such as the Kôgyô Dantai Dômeikai (Federation of Engineering Groups) that Muramatsu Tamitarô and his colleagues later established. Rumors spread that Dômei Shinkôgumi funds were being used in a corrupt manner, and the group was forced to break up. With all this experience of the labor movement behind him, Ozawa was one of the first to join the Ironworkers' Union and served in the Union's pre-eminent representive post as the Chairman of the Union Head Office Council.

No. 38 Branch which had organized at the Oki Electrical Works, had been formed around July 1899 and was still brimming with its early enthusiasm. Having opened the store at Hatchôbori, Fusatarô's decision to turn the upper floor over to a 'workers' clubhouse' for workers to socialize was not just for the sake of his own livelihood; he surely was aiming to restoke the energies of the Ironworkers' Union on the foundation of the Union branches at Ishikawajima and the Oki Electrical Works. But it proved no easy matter to run the store and carry forward his activities as central committee member at the Union head office. His wife Kiku was still breastfeeding their first child, and Fusatarô had to spend much time at the store. He spent many days pedalling to and fro on his bicycle between the store in Hatchôbori and the Union head office at Motoishichô.

'An aesthetic of manliness' - Takano gives up his remuneration

On January 30, 1900 the Ironworkers' Union held a 'Special Head Office Committee General Meeting'. The regular meeting was to have been held on the 21st but it had had to be postponed owing to heavy snow. The deliberations of the special general meeting were reported in detail by The Labor World. It is a rare case that we are able to know how Japan's first labor union conducted its meetings and the real state of the Ironworkers' Union were told by those who involved, including Takano Fusataro. So the citation is rather long, but it is worth looking in detail at how the meeting went.

Jan. 30, 7.30 p.m. meeting held at head office. The committee members took their seats, and the chairman first took the roll. (names omitted)

Chairman: 15 committee members are present, which constitutes over a third of the total and thus a quorum, so the meeting will now begin...

Chairman: A record of the meeting will be taken and will be printed in The Labor World. No motions have been submitted by the branches. Head Office has no motions to put forward either, so I am hoping that some of you will have something.

It was rather unnatural to arrange for someone to record the notes of a meeting with no motions from either head office or the Union branches, that is, a meeting where it was not even clear what was to be discussed, but Katayama Sen, the chief editor of The Labor World had probably arranged for that beforehand. The chairman's name was not recorded anywhere, but from the content of his remarks, it was almost certainly Katayama. There were 44 committee members altogether, so on this occasion 15 constituted the minimum for a quorum. It was noted that there were, besides the committee members, over 20 others present. It was a Tuesday, and many committee members were attending after a day's work, and so it is not surprising that many were absent.

The first issues for discussion were the finances and the current level of unionization.

Umakai (Chônosuke: No. 4 Branch delegate to head office) : At the previous special general meeting it was resolved to put into effect methods to reduce full provision of relief payments. Is there currently any prospect that such payments can be resumed?

Accounts manager Nagayama: Since the last special general meeting the Union's finances have been consumed ravenously, and debts have had to be incurred. We have had to take temporizing measures. We are going to repay this debt from this month forward on a monthly basis and intend to repay the debt, which is 300 yen, between now and June at a rate of 50 yen a month. Currently, relief payments are being paid at one fourth of their original sum and we should be able to maintain this rate of payment and expand our activities, but because we made inappropriate use of our remaining base capital before taking out the loan, we shall have to do so only after we have paid off the loan, otherwise it is very doubtful that we will be able to expand the newspaper and other activities. As for the collection of Union dues, if we manage to collect the amount we did last September and October, we shall get by, but if it is the amount of last November and December, that will not be enough. Large branches such as those in Yokohama and elsewhere, which had been remitting 30-40 yen each in dues were now sending only 7-8 yen or 12-13 yen. From now on, if we do not manage to return to the situation of last August and September, we shall have to cut production of the newspaper to twice a month and we shall then easily be easy to repay the loan, but with the present situation this cannot be guaranteed. We cannot take any adventurous risks.

Tanida (Hideshirô...No. 27 Branch delegate to head office): How many members do we have at present ?

Chairman: 2,500 names are registered on the Union list. However, those paying their dues in December numbered around 1,000.

Yoshizawa (Shûzô....No.30 Branch delegate to head office): When did the number of members begin to fall?.....

Chairman: We have not heard from all branches at this point, so we cannot be certain, but from investigations we have made here at head office, the fall began last September and had become significant by December.

These statements form an important record of the condition of the Ironworkers' Union in January 1900. In particular, from the chairman's last statement, it becomes clear that the onset of the fall in membership was in September 1899, and that by December there had been a sharp decline. It is also evident that in January 1900 there were about 2500 members of whom only 1000 were paying their dues. The finances were thus under great pressure, much of the basic capital had been used up, and the crisis had been averted by securing a loan from the bank, but the Union was left in a very tight corner.

The next topic for discussion was whether to return to a twice montly distribution of The Labor World from the once monthly system they had been forced to adopt by the financial difficulties, and if they were to do so, how could they contrive a way to afford it?

Umakai: My question is, I was wanting to return to a twice monthly distribution of The Labor World, and if the finances don't allow it, then it can't be helped, but if a newspaper that's published twice is distributed only once, then we shall only get half of any good discussion of issues....

Chairman: If the provision of relief money were reduced, your wish could be granted...

Takeda: A newspaper for a thousand people means no small amount of money.

Chairman: It would require 30 yen. Twice a month [distribution] would mean having to pay Kiseikai 5 sen per copy.

Takeda: We should pay 5 sen per copy.

Matsuo (Suketarô...No. 12 Branch delegate to head office How about distributing twice, raising the price per copy by 2 sen and the Union dues to 22 sen?....

Tanida: You all here may not think so but when you go to the branches the members there will tell you, as you know, that Kiseikai is of no obvious benefit to them. Many fellows say that it's no use joining it.

Next up for discussion was the proposal to raise the dues from 20 sen to 22 sen as an obvious way to solve the financial crisis. Although it was only over a matter of a two sen increase, it was rejected after hardly any real discussion. The opinion that 'it makes no sense to become a member of Kiseikai which brings no direct benefits' was widely shared among the membership and the fact that a rise in membership dues could not even become an issue at such a meeting shows the weakening of the centripetal forces that held the union together.

An important proposal was made next. It was proposed that The Labor World be distributed twice a month and that to guarantee funds for this, the number of members of excutive staff be reduced. The proposal came from Suzuki Hangorô, a Union council member. He was the deputy manager of accounts at the head office and a member of No. 30 Branch which was based at the Tokyo Arsenal small arms rifle body workshop.

Suzuki: I feel, after all, that The Labor World should come out twice a month. The level of dues is not sufficient for this. I am wondering where cuts can be made that will enable the costs of The Labor World to be met adequately ... Some may say that the movement should be contracted, but by reducing the number of executive officer to one, we can have a twice monthly distribution of The Labor World. If we can agree to drop one man from the excutive staff, we'll be able to distribute The Labor World twice a month.

As a major item of the meeting, this proposal may well have been partially discussed beforehand. It may also be that, at this meeting that supposedly had no agenda, the fact that a notetaker had also been prepared in advance was not unrelated to this proposal. The meeting accepted the poposal and discussion continued:

Matsuo: I am against it. Even at once a month The Labor World has to have two excutive staff. Just one will not be enough.

Suzuki: I think one is enough for office work.

Tanida: I'd like to hear about the work of the office staff.

Takano: As you members of the head office committee will be aware, I am of the view that the need for the appointment of executive officer goes without saying. Distributing The Labor World twice a month is certainly the desirable thing to do. At last December's general meeting it was resolved to resurrect this, but there has had to be a temporary retrenchment, and Mr Suzuki's proposal has resulted from the fact that the current condition of the finances does not allow a return to twice monthly distribution. Without saying that there must be a reduction to one executive staff, I believe it would be good to have one unpaid member of executive officer. I had been intending to suggest this to the council for some time but there was no opportunity to do so. As an executive officer I am paid 20 yen. I would therefore like this to be discontinued from January 1. I hope that this will suffice to cover the costs of the distribution of the newspaper. As the need today is to come to an agreement about how to cope with the financial pressure we are under, I think it would be really good if we had one paid and one unpaid member of staff. However, we would still be some 15 yen short, so I would like to hear views on how we can find a source of funds to fill this gap.

Fusatarô here had actually proposed that his own payment as executive officer be terminated. In effect, he had caustically commented that "I am not engaged in the movement for the sake of money". Of course, he was able to say such a thing because he thought that his livelihood would be securely based on his work as manager of the cooperative company. This proud man most certainly felt that he wanted to determine his advances and retreats in life by himself and did not wish to be in a situation where he was forced to quit by someone else. This was, so to speak, Fusatarô's 'aesthetic of manliness'.

When considering the question of a reduction in the number of the excutive officers, the candidate should not only have been Takano but also Katayama. From considerations of personal livelihood and of the amount of time that could be committed to the movement, Katayama was certqainly such a candidate. From the point of view of personal livelihood only, Katayama's situation was much more stable than Fusatarô's; he owned the Kingsley Hall in which he lived, he managed enterprises which yielded him an income such as a kindergarten and school and also earned an income from his writings. Nevertheless, the head office general meeting quickly moved to accept Takano's proposal and decided to confirm Katayama as an paid secretary and Takano as unpaid secretary. Anyone could recognize that the fact that the decision to remove Fusatarô's income could be taken so easily signified that, at that point, the leadership of the Ironworkers' Union had slipped from his hands.

The promulgation of the Public Order and Police Law

Just at the time when the Ironworkers' Union was struggling to cope with its financial difficulties, it was hammered from another direction - the Public and Police Law (Chian keisatsu hô). This was promulgated on March 10, 1900 and came into force on March 30, 1900. In marked contrast to the Factory Law that Kiseikai had wanted to see passed and which took almost 20 years to move from the proposal stage to enactment and enforcement, the Public Order and Police Law was passed by both Houses of the Diet after just 11 days' deliberations and was promulgated.

The Public Order and Police Law was passed as a revision of the 1890 Public Meetings and Political Societies Law (Shûkai oyobi seisha hô) and many of its clauses were continued from that earlier legislation. The Public Meetings and Political Societies Law was passed with the civil rights movement in mind and its main object was to regulate political activities. The Public Order and Police Law, on the other hand, was characterized by a series of new controls - those placed on the labor movement. It is quite evident that behind this change was the emergence of Rôdô Kumiai Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union, and then the Japan Railway strike and the Nittetsu Kyôseikai that was formed after the strike. The proposer of the new legislation, Arimatsu Hideyoshi, secretary at the Ministry of Home Affairs, gave the following explanation at the Diet as the 'reasons for the legislation'.

As you know, unions of laborers, that is, combinations are now active in Osaka, Tokyo and elsewhere, today even in Kyûshû, and it has become increasingly common for them to resort to strike actions when seeking changes in the clauses of work contracts or pay increases.... As you will know, as a result of a strike by workers at a certain railway company, the railway ceased operations for several days. That the public should have to suffer as a result and be to no small extent inconvenienced thereby, and that the situation has come to this point in today's society in which the rule of law obtains, is truly deplorable. Whether it be in this large factory or mine or that shipping transport or in other manufacturing concerns, when workers go on strike, it does not only cause damage to a single company, there are many cases of harm caused to society as a whole. Above all, were manufacturers who supply the armed forces with military equipment to be suddenly affected by strike action, it would have no small effect on the capacity of the military to perform its duties in time of war. For example, if during a war, arsenal workers went on strike, our military would be placed in an extremely disdvantageous situation. From the perspective of the national economy, it would not only cause great harm to our country but would lead to great inconvenience in our trade and other relations with foreign countries.

With his words as a result of a strike by workers at a certain railway company, Arimatsu was clearly referring to the locomotive drivers' strike at the Japan Railway Company and by if during a war, arsenal workers went on strike... he certainly had in mind the existence of the Ironworkers' Union, which had its main organizational base at the Tokyo Arsenal.

However, in the actual text of the new Law there are no clauses that provide for any prohibition of workers' unions. Perhaps that is why the preamble to the Bill included the following explanation:

In principle, the government recognizes workers' rights to form unions or take collective action in pursuance of wage rises or other claims. Consequently, it is the government's belief that excessive legal restrictions in such cases are not desirable in the present conditions of society.

Nevertheless, until its deletion in 1926, article 17 of the Law had the de facto effect of suppressing the labor union movement. What kind of ordinance was article 17? Let us look at the text:

The aims of the following clauses relate to those who seek to gain advantage from committing violence against third parties, or who seek to intimidate or defame [hiki] third parties. The aim of the second clause relates to those who entice or incite third parties.

1. Forcing others to join unions in order to engage in collective action in relation to working conditions and remuneration or attempting to prevent others from joining those unions.

2. Collective dismissals or strikes; employers' summary dismissal of workers or summary rejection of applications for employment; workers' refusal to work or refusal to accept notice of dismissal.

3. Obtaining by force the consent of others with regard to working conditions or remuneration

Hiki (defamation, defame) is a word not normally used nowadays but means to slander or libel someone. The text of the law appears to treat workers and employers evenhandedly, but of course, the concern and target of the bureaucrats at the Ministry of Home Affairs was actually workers, not employers.

Acts of violence, intimidation, and libel were all actions subject to punitive sanctions under the criminal law, but whereas in the case of normal libel, if the person libeled did not bring charges then there was no case to answer, under the Public Order and Police Law, it was at the discretion of the authorities to determine what constituted libel.

Another problem was the second clause, which actually had the effect of making strikes illegal. The clause prohibits 'the enticement or incitement of third parties' with a view to starting a strike, but a strike can hardly be expected to occur if someone does not take a lead and seek to persuade others. By regarding such attempts at persuasion as 'enticement' and 'incitement', strikes could be banned. This clause gave the police legal sanction to ban any strike at any time as they saw fit. The harsh penalty for violation was between one and six months' imprisonment, added to which was a fine of between 3 yen and 30 yen (clause 30).

Since its founding, the Ironworkers' Union had trodden a very careful line with regard to strikes. It did not deny the workers' right to strike but consistently followed a policy of seeking a solution to disputes by acting in a mediating role. Also, the head office of the Ironworkers' Union did not directly organise campaigns for wage rises and improvement of working conditions for those workers under its umbrella. When Union branches engaged in disputes the head office did no more than offer support by seeking to act as 'mediator in the dispute'; it strenuously tried to avoid supporting strikes as such. Nevertheless, it can well be imagined that the passing of the Public Order and Police Law would severely damage the movement in the future. On February 14, the day after the new law was passed, a 'Discussion on the Public Order and Police Law' was therefore on the agenda for discussion at the Union's next regular monthly meeting and the following points were resolved upon. [N.b. Article 18 of the published Law was Article 17 in the original bill]:

With regard to Article 18 of the recent Law and the question of how far it will impact the activities in which this Union has been engaged, we venture to believe that they will not be affected by the law. However, there is the danger that it will create difficulties for the Union to press for the workers' advantage when acting as mediator in disputes. Now that the law has been passed, we should, as soon as possible, call upon the head of the Office of Police, the head of the Office of Commerce and the chief of police and hear their views and accordingly, determine the stance of the Union thereafter. The Chairman has therefore delegated this task to three committee members: Katayama Sen, Nagayama Eiji, Sawada Han'nosuke.

The Ironworkers' Union, which, at its peak, had campaigned so vigorously for the Factory Law did not have sufficient strength left to mount a campaign against the passing of the Public Order and Police Law which was feared would have such a direct impact on the union movement. But even if it had had had the requisite energies they could not likely have been mobilized in the mere 11 days it took between the submission of the bill and its passing into law; there simply was not sufficient time.

However, The Labor World came out strongly against the new law. The front page of issue no. 56 (March 15, 1900) carried a critical article by Katayama Sen titled 'Workers and the Public Order and Police Law'. The 'Miscellaneous Reports' column included the article "The Public Order and Police Law Means Suppression"by Kôtoku Shûsui, while in the 'Features' column was an article titled "Oh no, here comes a law of repression" by Nishikawa Mitsujirô.

It has been claimed repeatedly that it was the Public Order and Police Law that crushed the newly-born Ironworkers' Union. Many have argued that the Public Order and Police Law was 'the death sentence for labor unions' or 'the union-banning law', and certainly, the law did have a considerable negative impact on the Ironworkers' Union. However, it was not the case that the Public Order and Police Law soon forced the Union to disband. The fact of the matter was that the rot had set in at the Ironworkers' Union even before the law was passed.

|

This file was last modified on: November 29, 2014. |

Top page in English |

prev.:12. The Opening of the Yokohama 'Cooperative Store' - Pioneer of the cooperative movement next: 14. Takano Fusatarô and Katayama Sen - their leadership qualities. |