Chapter 15 Death in China

- Evaluation of Takano Fusataro -

Takano's withdrawal from the labor movement

On August 24, 1900, together with Katayama Sen and Abe Iso'o, Takano Fusatarô spoke at a public meeting at the Sueyoshiza theater in Ômiya Town in Saitama Prefecture. In Ômiya were the Ironworkers' Union's strongest branch, the No.2 branch, and the main workshops of Japan Railway Company, the base of the branch's organizational support. However, in March that year, after a campaign for better conditions, the leading union activists had been discharged, ordinary union members had been forced to quit the Union, and the branch was in state of collapse.

September 1, 1900 issue of The Labor World published the following report of Fusatarô's speech on that occasion:

Mr Takano pointed out the errors in the company's opposition to the Union, cited a number of cases from western countries, and claimed that a sympathetic attitude on the part of the company towards the Union would lead not only to the benefit of the individual workers but also to the benefit of the company. He inveighed against the Ômiya Works' folly in closing down the Union and concluded his remarks to thunderous applause.

This speech marked the beginning of Takano Fusatarô's departure from Japan. It was his last speech, and after it, he left the labor movement and moved to China. Three years after calling for the formation of labor unions in the publication of A Call to All Workers (Shokko shokun ni yosu), Takano Fusatarô, with broken sword and not an arrow left in his quiver, so to speak, turned away from his goal of rooting labor unions in Japan. The same issue of The Labor World reported his decision in a brief note:

Mr. Takano Fusatarô will shortly be leaving for China. Having worked arduously for the cooperative store and given great encouragement for the founding of our Union, he is now going over to China where he will no doubt do great things. We wish him good health and safety and look forward to his return after the achievement of his goals.

The note tells us nothing of why he was leaving Japan or where in all of China he was going. There was, however, another short note in the English column of the same issue.

Mr. F. Takano has Just gone toTentsien where he will start a store with his old chum Joe Tsunetaro. A big success to them !

So from this note in English we know that he was bound for Tianjin and was planning to set up a business there with his old friend Jô Tsunetarô. The Japanese text suggests he had not yet left, but from the English text one understands he had already done so.

What then were the reasons why Fusatarô decided to withdraw from the labor movement? In fact, at one time, and especially among old historians of the social movement by the 1950s, it was suspected that Takano Fusatarô left the labor movement because of some personal scandal; there were even those who imagined 'a conversion' or 'a betrayal'. Most only expressed their thoughts or speculations in conversation and few went as far as publication. One of them was Tanaka Sôgorô in his book Kôtoku Shûshui:

There seems to have been a personal reason [for Takano Fusatarô's withdrawal from the labor movement]. His brother Takano Iwasaburô did not in the end give any explanation for it during his lifetime..... I once called on Takano Iwasaburô in the NHK Chairman's office and he showed an awkward expression when this question came up, gave a rather apologetic answer and said that he would write something about the matter, but he died the following year, to my great regret.

What brought this question to Tanaka Sôgorô's attention was his understanding that Fusatarô had left the movement just when it was at its peak. In the above-mentioned book, he wrote:

In 1899 the Union expanded to 40 branches and in September 1900, with the opening of the 42nd branch at the Ishikawajima Yard at Uraga, it had over 5,400 members. The organization had reached its peak.

However, this was not based on a correct reading of the historical records but rather, on the following account given in Nihon no rôdô undô (The Labor Movement in Japan) by Katayama and Nishikawa:

The number of branches continued to grow in 1899; in July western-style furniture makers in Yokohama joined the Ironworkers' Union and set up Branch No. 41, and in September, Branch No. 42 was opened at the Ishikawajima Yard in Uraga. The total number of members now exceeded 5,400.

In September 1900 there was a dispute at the Uraga Ishikawajima Shipbuilding Yard, and this may have been what led to the establishment of the Union's No. 42 Branch. But at this time, most other branches were collapsing or had already disappeared. Moreover, the figure of 5,400 members was not that of the members who were actually registered at that time, but was in fact recorded in an appendix to The Labor Movement in Japan as the total number of new members who had joined since the founding of the Union. September 1900 was hardly the peak of the organization; on the contrary, the Union was a state of collapse. If Fusatarô had indeed suddenly left the movement at its real peak, it would be only natural to suspect some personal motive such as 'conversion' or something else, but in fact, both Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union had already ceased to be mass organizations. That Fusatarô himself has left no explanation of why he withdrew has given rise to further speculation. Two who were close to him have left accounts that help us to get an inkling of an answer. One was his colleague and friend Yokoyama Gen'nosuke, who wrote Fusatarô's obituary in the Mainichi Newspaper. In it appear these words:

Driven onwards, the labor movement grew and grew but after one or two years it was deadlocked, and the consumer union for which you did your utmost ended in failure, but once again you sought to go into business and make your own way. At the time I had a chronic illness and returned home to recover, and you wrote to tell me what was in your heart; you promised you would " work patiently for ten years and then once again serve the workers' cause". Having thus promised, you departed.

According to Yokoyama's testimony, Fusatarô left the labor movement because it was 'deadlocked' and because the consumer union had 'failed', but he had clearly not given up on the labor movement and after ten years of patient waiting, he said he would return to work for the cause of labor once more. Just three and a half years after he wrote that letter to Yokoyama, Fusatarô died and so was unable to carry out his intention.

A second account is given by his brother Iwasaburô in his short biograpy of Takano Fusatarô for the Dai-Nippon Jinmei Jisho (Lexicon of Famous Japanese):

However, the fortunes of Kiseikai and then the cooperative store both finally began to wane, and in 1900 he left Japan, went over to northern China and wandered from place to place.

From this we learn that not only did Kiseikai go into decline but also the cooperative store, which had given him his livelihood. In fact, it was not only the store operated by Fusatarô; all the cooperative stores that had started up in various locations eventually failed. One reason was the collapse of the Union, which had been parent organization of them, but there was another, even more important reason. In Japan at that time, all stores sold goods on credit. The cooperative stores could not therefore apply the cooperative union movement's basic principle of 'cash sales only' and had to stick to the credit sales system. This was the common reason for their demise.

For Fusatarô, who had given his all to the Union and the cooperative movement, to witness the collapse of the Ironworkers' Union and then find his way blocked as manager of the cooperative store, the last business into which he had put his energies, there was no other choice now but to take some other path.

Takano heads for a China in turmoil

China at the time when Fusatarô moved there resembled a battered and wounded old whale which had been attacked by a school of greedy sharks. The competing Great Powers had moved into China and had taken over effective territorial control of strategically important regions under the pretence of 'leasing' them from the Chinese government. They were eagerly exploiting their various opportunities by laying down railroads and opening up mining development projects.

In response, the Qing government of the Regent Empress Dowager Cixi and the Guangxu Emperor had no means of coping with the foreigners and were continually forced to make concessions. Defeated in one war after another - the Opium War, the 'Arrow War' (Second Opium War), the Sino-French War, and the Sino-Japanese War - the Qing had not the strength to resist the encroachment of the foreign Powers.

In November, 1897, taking advantage of the murder of one its missionaries, Germany occupied Kiaochow (Jiaozhou Bay) and took control of the fort at Qingdao which commanded the bay area. The following March, Germany succeeded in securing a leasing arrangement for Kiaochow. In a competitive response to this German move, Russia sent a naval squadron to Port Arthur (Lüshunkou) and acquired leasing rights in Dalian and Port Arthur and the right to construct the Chinese Eastern Railroad (later the South Manchuria Railway). Great Britain too intervened by occupying Weihaiwei at the north east end of the Shandong Peninsula, obtained a lease for it and also for Kowloon (the New Territories) opposite Hong Kong, which it had possessed for half a century already. France occupied Guangzhou (Canton) and obtained a lease there, and Italy demanded the lease of Sanmen Bay. Competition between the imperialist Powers for slices of Chinese territory was hotting up.

The Chinese people's frustration at these foreign moves exploded, and an exclusionist, anti-foreigner and anti-Christian movement suddenly burst out, led by the Righteous Harmony Society ('the Boxers'). The Society had emerged in Shandong province in 1898; its aims were the exclusion of 'evil religion' i.e. Christianity, and the extermination of westerners. Its members belonged to a cult-like martial group that practised a martial art known as the Righteous and Harmonious Fist and went into battle chanting incantations, claimed to have supernatural powers due to swallowing magical potions and believed they would be invulnerable to sword cut or artillery shell. With these 'powers' they hunted down western missionaries and the Chinese Christians who followed them. They attacked churches and committed acts of violence against Christians, destroyed railroads and other facilities; their activities steadily increased and their strength rapidly expanded, especially in north-east China. At their peak they numbered 200,000 in Beijing alone, and their influence reached into the highest echelons of the Qing Court as they became a publicly acknowledged organization.

In June 1900 the foreign legation area in Beijing was surrounded and besieged by the Boxers and the Imperial Army and supplies of food to the 4,000 foreigners and Chinese Christians inside the area were cut off. At this point an allied army consisting of troops from eight nations - Britain, America, Germany, France, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Russia and Japan (the largest contingents were from the latter two countries) - advanced on the capital from Tianjin to relieve the Legation Quarter. The Qing Court responded by declaring war upon the eight allies. The allied expeditionary force soon began to win victories and in mid-August Beijing was taken. Fusatarô arrived in China just after the end of this 'Northern China War', as it was known in Japan. The place where he landed, Tianjin, the location of the first battles of the war, and the scars of the fighting were still all too evident.

Only fragments are known of Fusatarô's activities from his arrival in China at the end of August 1900 until his death there, 'in a foreign land', three and a half years later. Occasional brief in reports The Labor World only mentioned his movements. Issue No. 67 (Nov. 1, 1900) carried the following report:

Mr. Takano Fusatarô returned from Tianjin on the 5th last, established the Northern China Trading Company and returned again to China.

So only a month after arriving in China, Fusatarô returned to Japan on October 5, set up the 'Northern China Trading Company' (Hokushin Bôekigaisha) and went straight back again. The name of the company suggests that he had in mind a trading business between China and Japan.

From earlier reports it seemed that Jô Tsunetarô had accompanied him to China but in fact, Jô arrived in Tianjin in Febrary 1901, and before his arrival Fusatarô had already moved to Beijing. The English language column of The Labor World No.69 (January 1, 1901) included the following news:

Mr F. Takano has moved from Tentsing to Peking where he will start a store.

The report cites the purpose of the trip as being "to start a store", but actually it was to work for the German army, as we learn from the English column of The Labor World for January 15:

Mr. Takano has returned to Bakan [the old name of Shimonoseki] on business and sent to us a happy new year. He will be in Pecking [sic] after few days stay at Bakan. He is in a German army.

Beijing was then under occupation by the armies of the western Powers, following their suppression of the Boxer Rebellion. The largest foreign contingent in the occupation was that sent by Germany - 24,000 troops. The Commander-in-Chief of the allied armies was also a German. It was to this German army of occupation in Beijing that Fusatarô now turned.

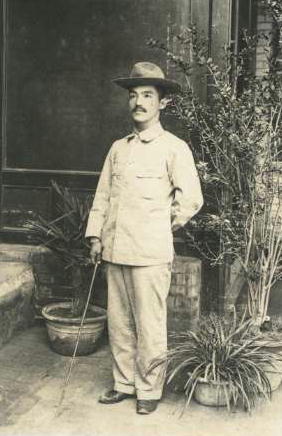

Having deployed such a large force, the German army certainly had no need of foreign auxiliaries. Already over 30 years old and small in stature, Fusatarô would not have been taken on by any of the occupation forces. One can only imagine that the German army would have needed his language abilities, his ability to read and write Chinese characters, his Japanese language fluency, and his ability to gather and translate information based on his excellent English. Information gathering in this case would not have meant espionage but rather, translating into English information gathered from newspaper and magazine reports. His brief return to Japan would no doubt have been to collect the Japanese language resources (newspapers etc.) he needed.  That he worked for the German army after his return to China is verified by one or two pieces of circumstantial evidence. One is the fact that on the back of the photo above is written: Taken June 27, 1901, 4 days before leaving Beijing.

That he worked for the German army after his return to China is verified by one or two pieces of circumstantial evidence. One is the fact that on the back of the photo above is written: Taken June 27, 1901, 4 days before leaving Beijing.

At that time, the allied armies were still in Beijing in order to ensure the suppression of the Boxers. The Powers were engaged in negotiations with the Chinese government with regard to punishments of those responsible and the payment of financial compensation. With the negotiations almost concluded, the allied forces began to withdraw from Beijing in July 1901. Fusatarô left Beijing on July 1. Another piece of circumstantial evidence is the fact that after leaving Beijing, Fusatarô headed for Qingdao (then romanized as Tsingtao, or Tsingtau by the Germans). Qingdao was the city that served as the administrative center of the German concession territory of Kiaochau (the German romanized form of Jiaozhou Bay) and as the main base for the German army and navy in China. It is not known what exactly Fusatarô was doing in Qingdao. One suggestion is that he was engaged in a trading business with his friend Takekawa Fujitarô. The two met in San Francisco and he had been the editor of San Francisco's Japanese language newspaper Ensei, for which Fusatarô had written articles. However, even supposing that Fusatarô was working in a trading business it is likely that he was still working for the German army. This is evidenced by the fact that when he became ill he was treated at the German hospital in Qingdao.

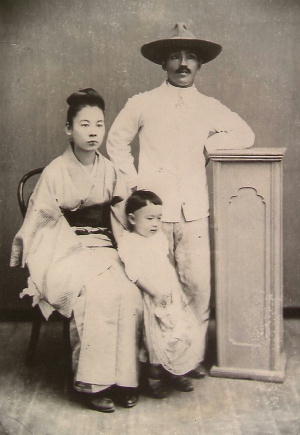

It is hard to imagine that at the outset he would have taken his family with him to a foreign country he did not know well, so it is likely that Kiku and Miyo joined him in China after he had returned to Qingdao. Whatever were the facts of the matter, the two and a half years that Fusatarô spent in Qingdao were a comparatively quiet period in what had been until then a life of continuous change. Throughout his time in America and after returning to Japan too, Fusatarô had continually been on the move. The urge to follow some new impulse had led him to relocate time and again. He may have relocated within Qingdao but he was now free of the hectic activity of the labor movement and for a change, was probably able to enjoy a quiet lifestyle. Facing the sea, and with its many streets of western-style buildings, Qingdao must have reminded him of San Francisco. But Qingdao had only just commenced on its urban development, so it may also have reminded him more of Tacoma.

A major development for the Takano family during their years in Qingdao was the birth of their second daughter Fumi on January 18, 1903. Fusatarô's mother Masu came over from Japan to help with the birth. Miyo had been born at the family home in Japan, and so no-one was more suited to help out at this time than the experienced grandmother Masu.  The commemorative photo here was taken in Qingdao on February 25, 1903, the day before Masu departed for Japan. From the clothes everyone is wearing, and above all from the fact that such a photo was taken, we can imagine that Fusatarô's family were living rather comfortable life. Probably his trading business and the earnings from the German army, Fusatarô might obtain an adequate income to support his family.

The commemorative photo here was taken in Qingdao on February 25, 1903, the day before Masu departed for Japan. From the clothes everyone is wearing, and above all from the fact that such a photo was taken, we can imagine that Fusatarô's family were living rather comfortable life. Probably his trading business and the earnings from the German army, Fusatarô might obtain an adequate income to support his family.

However, this peaceful lifestyle did not continue for long. From the second half of 1903, Fusatarô's health began to suffer. The liver abscess that would take his life had probably begun to develop. We know this from a letter to Masu from Katayama Sen dated November 23, 1903 The main point of the letter was to ask Masu to reply to an earlier request for her to recommend a maidservant, but at the end of the letter he writes: "I have heard that your son is ill". The liver is known as 'the silent organ', and liver diseases are known to develop quietly without many external symptoms, but if they had already appeared then that would certainly have meant that the illness was at an advanced stage.

Death in China

The journey of Fusatarô's life ended on March 12, 1904. He was 37 years old according to the traditional Japanese dating system as he had been born in the first year of the Meiji era, but he actually lived for 35 years, 2 months and 6 days. A month before he died, the Japanese navy attacked the Russian fleet at Port Arthur, and the Russo-Japanese War began. Port Arthur (now Lüshun City) was the main base of the Russian navy in the Far East. It is located at the tip of the Liaodong Peninsula, across from the Shandong Peninsula, to the north-east. Takano Fusatarô, who had been born at the very beginning of the Meiji era, died in a foreign land, not far from where great battles would soon be fought between Meiji Japan and Imperial Russia.

The cause of death was a liver abscess. The protozoan that causes amebic dysentery breaks through the intestinal membrane, enters the bloodstream and then the liver, where it creates an abscess. This produces symptoms such a swelling of the liver, severe pain, fever, vomiting and loss of appetite. Amebic dysentery was widespread in China in those days, and after moving there from Japan he may well have been infected by eating seafood that had been cooked in water that was insufficiently boiled. In the German hospital in Qingdao he would probably have received the best medical treatment then available, but he died after 'all treatment proved ineffective'.

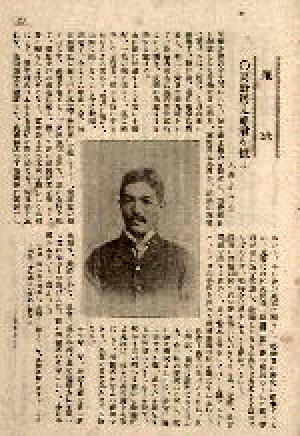

News of his death reached his friends in Japan nearly two months later. His colleague and close friend Yokoyama Gen'nosuke wrote an obituary in two parts in the Mainichi Shinbun newspaper on May 4 and 9, 1904. Titled "A Pioneer of the Labor Movement Dies", it described Fusatarô's career and his achievements in the labor and cooperative union movements and quoted the following words from Fusatarô's brother Iwasaburô:

Your younger brother, university professor Takano, in deepest grief, now says: "my brother was a failure"; he left this world without success in any of his personal or social undertakings.

A Man of Failure

The idea that Fusatarô had been 'a failure' was not only that of his brother but was shared by the whole Takano family - his mother Masu, his sister Kiwa, and his brother-in-law Iyama Kentarô. The family had held high hopes of Fuastarô, who, having lost his father at an early age, had become the head of the household. Fusatarô himself, however, who had excelled at school and had never known failure, thinking that success in business would soon be his, went over to seek his fortune in America, full of enthusiasm. But the reality turned out to be much harder, and after the failure of his Japanese goods store, he had had to take a series of jobs such as waitering in a restaurant and while enduring a hard time studying, he had sent money back to Japan. Finally, he had returned to Japan after serving on a US warship in order to pay back his debts. Apart from his brother Iwasaburô, no-one else in the family could understand why he then put all his energies into the labor movement and the cooperative movement. But those efforts too had ended in failure, and then his endeavor to start again in business, this time in China, was frustrated by his early death. It was hardly surprising that Fusatarô would have been regarded as a failure. More than anyone, before his death Fusatarô himself would have bitterly regretted that his life had been a series of failures. The collapse of Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union, which had at one time seemed so full of promise, must have been especially galling. Having left his homeland with the intention to "work patiently for ten years and then once again serve the workers' cause", that he had succumbed to illness after only three of those ten years and that his life had come to an end in a foreign country must have caused him intense regret and sorrow.

A Man of Success

But just before Fusatarô's death, the Takano family had had cause for great rejoicing. In April 1903 Takano Iwasaburô had returned home after four years' studying in Germany and in May that year was appointed full professor in the Law Faculty at Tokyo Imperial University, although in May 1900, while still at his studies in Germany, he had been made an assistant professor, so the appointment to the eventual full professorship was to be expected. As head of the household in place of his father, this was a source of great pride and joy for Fusatarô. For many years he had endured a life of poverty but had continued to support his brother's studies by the money he had sent back home, and now his brother had achieved the highest academic status of a full professorship. But along with this happiness for his brother, who had been able to devote himself to his studies and make such progress in them, Fusatarô may well have felt a kind of jealousy. He himself had been ardently interested in economics and had built up a collection of books and texts on the subject, and the fact that Iwasaburô came to specialize in economics owed not a little to Fusatarô's influence. But the more that Iwasaburô was praised and complimented, the more aware Fusatarô must have been of his own 'failure'. For Fusatarô, who held self-respect so highly, this gap between him and his brother must have been a source of great dissatisfaction. This emotional discomfort must have added to the bitterness of the days in the last year of his life, in 1904, as he lay on his sickbed, racked with pain.

Yet I do not think that Fusatarô spent those last days filled with thoughts simply of failure and regret. He was an innate optimist and he would somehow have reflected that although his life had been 'short', it had been full; he had seen something of the world and had had many varied experiences. It had been a rare and an interesting life. This is what I like to imagine he would have felt.

Yokoyama Gen'nosuke's memories of his friend

His funeral was held at Qingdao and his body was cremated there. His ashes were returned to Japan in late June, and on June 26 the interment ceremony was held at Kichijôji, the famous temple of the Sôtô Zen sect in Hongo-Komagome.

The day before, Yokoyama Gen'nosuke once again put pen to paper to write "Remembering Takano Fusatarô" (Takano Fusatarô-kun wo omou); he published it in the first issue of Tôyô Dôtetsu Zasshi (Eastern Copper and Iron Magazine) of which he was the editor. It is an important record that gives an account of how Fusatarô and Gen'nosuke recognized and trusted each other and how, thanks to Fusatarô's efforts, Yokoyama was able to take part in the Shokkô Jijô (The Workers' Situation) survey. The full text is quoted below. To add a word about the Shokkô Jijô, its appendices, especially the Conversations with Workers (Danwa hikki), presented a detailed account with a liveliness rarely seen in official surveys.

The day before, Yokoyama Gen'nosuke once again put pen to paper to write "Remembering Takano Fusatarô" (Takano Fusatarô-kun wo omou); he published it in the first issue of Tôyô Dôtetsu Zasshi (Eastern Copper and Iron Magazine) of which he was the editor. It is an important record that gives an account of how Fusatarô and Gen'nosuke recognized and trusted each other and how, thanks to Fusatarô's efforts, Yokoyama was able to take part in the Shokkô Jijô (The Workers' Situation) survey. The full text is quoted below. To add a word about the Shokkô Jijô, its appendices, especially the Conversations with Workers (Danwa hikki), presented a detailed account with a liveliness rarely seen in official surveys.

I am convinced that Yokoyama Gen'nosuke was its only author, but in the background, the prime mover for it and the man who made it happen was Takano Fusatarô.

A pioneer of the labor movement and founder of the Ironworkers' Union and the Cooperative Union, you Takano Fusatarô were a bright star in the workers' movement. Three months have gone by already since your passing in Shandong Province in China. When I heard that a few days ago your ashes had arrived in Tokyo and at 9 a.m. on June 26 were interred at a ceremony at Komagome-Kichijôji I could not restrain the deep emotion that welled up within me.

I have wandered from place to place these past 10 years and I have just about managed to earn my living by writing. There have been some difficult times. I went to the countryside and hid myself several times. I recall it was some 6 years ago when I was working at the Mainichi newspaper - I finished editing Nihon no kasô shakai (The Lower Classes in Japan) and my health was poor and using the summer heat as an excuse, I suddenly left Tokyo and went to my seashore homevillage Oto via Kanazawa. I decided to go back to farming and abandon journalism. The one who advised me most strongly against doing that was you, and the following year when you were very busy preparing to leave Japan, even at that time you did not forget me and arranged with Professor Kuwata [Kumazô] for me to be involved in the factory survey organized by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. Now I am back in Tokyo and I am working on research into workers' issues. Of course I have my seniors Mr. Sakuma Teiichi and Mr. Shimada Saburô, both of whom have supported me a great deal, and their support has been really valuable, but I must say that you always encouraged me and pushed me on and I must acknowledge that. Ah.... I can't forget you. It's not just my personal sentiment that makes me regret your death. These days there are many peple who discuss social problems, and there are the socialists who follow Karl Marx's school, which advocates that capital should be publicly owned. So there are those who talk about social issues and eventually that produced those socialists, so it's good that socialists are emerging and though their theories are very extreme, still it is just social theory. So I don't really agree with socialist theory but one can't really exclude it. It would be narrow-minded if one tried to do that. But when one looks at the actions of those who advocate socialism, they deliberately make their theories really extreme and they don't really think about the workers, and that is why I cannot really agree with them. Year by year, the number of people who approve of socialism is increasing. At such a time, the loss of someone like you who rejects socialist theory and their type of movement is a real pity for the workers and a pity for Japan as well.

A month after the obituary in the Mainichi Shinbun, Shakaishugi (Socialism), the successor to The Labor World, also reported on the death of Fusatarô. Katayama Sen was abroad at this time, so the piece was probably written by Nishikawa Mitsujirô. Compared to the deep feelings in the obituary written by Yokoyama Gen'nosuke, this was short, curt, and replete with errors. It is inevitable that a writer who did not know the subject would produce something that sounded dry and official, but sentences such as "he [Takano Fusatarô] started Kiseikai together with Katayama Sen and Suzuki Junichirô" and estimations of Takano's role in the Ironworkers' Union that described it as 'providing assistance' made this the first of what would later become "biased estimations of Takano Fusatarô".

How to estimate Takano Fusatarô?

At the end of his obituary for Fusatarô titled "A Pioneer of the Labor Movement Dies", Yokoyama Gen'nosuke continued on from Takano Iwasaburô's words "my brother was a failure" as follows: "but his work in those two or three years wrote the first page in the history of the labor movement, so he was not without a success." I can agree with Yokoyama's assessment. Fusatarô was a failure in the world of business, but it is clear that he was a leading light at the very beginning of the history of Japan's labor movement. I would like to reappraise Takano Fusatarô's role in the early labor movement and underline my estimation of the man.

The first of his achievements that ought to be stated is that at a time when Japanese were not even familiar with the words 'trade union' and 'labor union', Takano Fusatarô was the first to understand the significance of unions and to inform his countrymen of that significance. This was a real personal achievement on his part. I have already discussed this in "Message from America - The first call for labor unions in Japan" and elsewhere so I shall not repeat it here.

Takano's second achievement was that he was at the center of the Friends of Labor (Shokko Giyûkai), first founded in San Francisco and re-established in Tokyo; the group was the origin of the Japanese labor union movement. There are still arguments to the effect that Takano was not present at the founding of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco or at its re-establishment in Tokyo and that he was not a central figure, but I have already shown that there is no evidence to support those claims. He was indeed the central figure at both the founding and the re-establishment of the Friends of Labor.

The third and most important point is Fusatarô's historic contribution as the man who built up the organization of Japan's first labor union from scratch. Takano Fusatarô was not just an advocate of labor unions who spoke about the significance of unions; he thought through what kind of organization would be needed if unions were to be successful in Japan. Instead of moving to organize unions straightaway, he conceived of a preparatory step - a body to promote and propagandize for the labor union movement and he organized that body himself. From the beginning of the movement, he devoted all his energies and resources to it for nearly two years as the only unpaid official of the Friends of Labor and Kiseikai.

Many texts of modern Japanese history, including history textbooks, cite Takano Fusatarô and Katayama Sen as the joint 'founders' of Kiseikai, but when one looks into the details of how Kiseikai came about, it is clearly an error to equate the roles of the two men. One can only conclude that as the actual founder of Kiseikai, the man who should first be named is the one who conceived of the organization and then carried it through to realization - Takano Fusatarô. If others are to be mentioned, then they should not be Katayama Sen, but Takano's friends from his time with the Friends of Labor in San Francisco and Tokyo - Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Hannosuke. Next would be the names of those who played an important role as helpers at the time of the founding of Kiseikai - Sakuma Teiichi and Suzuki Junichirô. Katayama Sen, whose name is commonly cited alongside that of Takano Fusatarô, gradually increased his profile as a leader within the movement after the founding of Kiseikai and especially after the appearance of the first issue of The Labor World, when his influence grew, but until Kiseikai was actually founded, he was no more than someone who rendered assistance.

Fourthly, Takano Fusatarô was also the man who contributed the most to the theoretical and practical development of the cooperative movement in Japan. He first realized the importance of the movement in 1891. He understood the important need for union members to benefit practically from belonging to a union besides their mere membership and that this was necessary to support the stability of the union; he drew up model principles for a cooperative store, which he then propagated throughout the labor movement and at the same time founded two such cooperative stores in Yokohama and Hatchôbori in Tokyo, both he himself managed.

Unfortunately, in none of these ventures - Kiseikai, the Ironworkers' Union, and the cooperative stores - did Fusatarô prove to be 'a success'. All of them survived for only a very short time and in the world of the social movement too, Fusatarô was seen as 'a failure'. But the responsibility for these failures cannot be attributed to him personally; rather, they were the result of historical and social pressures. Whatever policy he had tried to adopt, it would not have been possible to keep these organizations going.

Takano Fusatarô's firing of the impulse of the labor movement had all kinds of influences, great and small, on those who took part with him in the movement and on those who came after, as well as on the whole social movement in Japan. For example, if Katayama Sen had not met Takano Fusatarô, he may well have spent his life as a Christian social reformer.

One of the direct influences on the social movement of Takano Fusatarô's activity that can be cited is the birth of Japan's first socialist political party, the Social Democratic Party (Shakai minshutô). Katayama Sen was of course the central figure in this, but what clearly shows that the party was founded on the basis of Kiseikai and the ironworkers' Union is the fact that the four meetings that were held to prepare for the founding of the party all took place at the Ironworkers' head office at Hongokuchô, in Nihombashi, Tokyo. Moreover, the 'Declaration of the Social Democratic Party' that was decided on at those meetings was published as a special issue of The Labor World.

Besides his influence on Katayama Sen, Takano Fusatarô's influence extended widely, in all kinds of ways great and small, among many people, both well-known and unknown, who participated in Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union and also afterwards. In fact, hardly any of the names are known of those workers who were members of the Ironworkers' Union after 1900, but from the examples of fragmentary evidence we do have about the circumstances of those later workers, it is clear that the influence of the movement that Takano Fusatarô began did not fade with the demise of the Ironworkers' Union. One example here is that of Umakai Chônosuke. A member of the branch committee of No. 4 Branch of the Union, and also branch accountant, he served on the Kiseikai standing committee. During his membership of the Union, Umakai worked at the Ministry of Telegraphs and Communications' telegraph pole equipment-making factory and later became a foreman at Nippon Denki (NEC). It is known that at the time of the revival of the labor union movement during the First World War, through his connections with Sôdômei (Japan Federation of Labor) activists, Umakai stealthily employed a number of them, thereby rendering support to the movement.

Most of the workers who joined the Ironworkers' Union were skilled men who, even after being laid off, had no difficulty finding work at other large workplaces up and down the country. Many workers, such as Muramatsu Tamitarô, who were either sacked or quit their jobs at the army arsenal simply slipped over to the new navy arsenal at Kure. In many of the labor disputes that flared up after the Russo-Japanese war, it is recorded that a leading role in those disputes was played by 'veterans' of the Ironworkers' Union. Rôdô wa shinsei nari (labor is sacred) - the words Fusatarô used in "A Call to All Workers" and which he had printed on the back of his namecards continued to be a key motto within the Japanese labor movement, as is only too clear from the fact that the founder of Yûaikai, Suzuki Bunji, used those words Rôdô wa shinsei (labor is sacred) as the title of his book.

To sum up, it can thus be confirmed that Takano Fusatarô influenced the birth of the Japanese labor union and cooperative movements and the subsequent development of the Japanese social movement in various ways. Of course, these were mass movements, which Fusatarô did not bring about all by himself. Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union were both the crystallization of the efforts of many people, known and unknown. But it is also clear that at the very center of those efforts was Takano Fusatarô.

The Japanese cultural climate and the labor union movement

In listing the names of those who worked hard for the founding of the Ironworkers' Union, we should not forget those progressive-minded workers who served as the Union's officials, such as Muramatsu Tamitarô. Their role has not been properly evaluated until now, but it was their energy that made possible the rapid growth of the union. Japanese workers were not as 'ignorant' as Fusatarô thought. Although the number may not have been great, there were indeed workers who could understand a difficult text such as "A Call To All Workers" (Shokkô shokun ni yosu) and who eagerly read The Labor World. Naturally, the capacities of Japanese workers as a whole were not yet that great. That is only too evident from the fact that the Union was pushed to the point of financial breakdown by its inadequate income from union dues and by pressure from owners. Yet in terms of mental capacity and zeal for the movement, there were a certain number of workers in Japan who compared favorably with 'intellectuals'. That accounts for why "A Call To All Workers" was able to make the impact it did in such a short time. These men were more eligible to be union leaders than Takano or Katayama. The problem was that they would not likely have been recognized as leaders by men outside their own workplaces.

What became clear from Fusatarô's social 'experiments' was the difficulty of establishing a labor union in Japan. Of course, the path of the labor movement has not been an easy one in any country. In America for example, guns were used in the suppression of many labor disputes, resulting in numerous deaths. Nevertheless, the union movement did manage to put down firm roots in American society. This was because there was a pre-existing cultural 'soil' in which organization could spontaneously grow. Both the AFL President Samuel Gompers and George Gunton, the author of Wealth and Progress were immigrants from England, and the fact that they were union activists shows that immigrants from Europe brought their mother country's social customs with them to the New World. Everywhere in America therefore there was suitable soil in which self-reliant, autonomous workers' organizations could take root and grow.

By contrast, Japan more or less resembled a barren desert, lacking the conditions that would facilitate the spontaneous growth of such unions. The very lack of any tradition of self-reliant, autonomous occupational groups created that organizational climate. There was not what could be called a firm comradeship among fellow artisans of the same craft and effectively no feeling of working class solidarity. Japan was not a country in which workers abided by the rules of their own autonomous organizations as in the West but rather, one in which there was the strong tendency to protect their occupational interests by depending on their social superiors. It goes without saying that those in authority, and the rest of society as well, did not acknowledge the self-regulating rules of autonomous groups. In such a social climate, that over 5,000 men responded to Fusatarô's call to combine in a labor union ought in itself to be regarded as a great success.

Subsequent history shows that in Japan, there was no other way for labor unions to root themselves, however scantily, than by cultivating a feeling of workers' solidarity through shared experience in labor disputes. In passing, it should be noted that these disputes often featured demands for "recognition of workers as proper members of staff within the company" and demands to "treat workers as human beings". Fusatarô's declaration that "labor is sacred" continued to appeal to the feelings of Japanese workers and was echoed in such demands.

Another reason why labor unions could not easily root themselves in the soil of Japanese society was due to the political climate. Labor unions in every country require large numbers of workers to assemble in public. Labor unions cannot be illegal secret societies. It follows that for unions to be able to develop, it is crucially important that the right to form combinations is legally affirmed. Fusatarô learned that in the very first letter he received from Gompers. At first, he had thought of starting the movement only after petitioning the Diet for a new labor union law. But in Japan in the decades before World War II, passing labor union legislation was no easy matter. Subsequent history made it clear how difficult this was. The right to form unions was only recognized in Japan almost half a century after the formation of the Ironworkers' Union and was only first realized in law through the radical reforms that followed defeat in war.

The people Takano left behind

When Fusatarô died, his wife Kiku was only 22 years old and faced the prospect of many years of widowhood. Her name was soon removed from the Takano family register and the following words were added in the appropriate column:

November 22, 1904, Reported that Kiku would be transferd into the family of commoner Yokomizo Ryûtarô, 1 Gofukuchô, Nihonbashi ward. Received by registrar Ôba Tomoe on the same day.

December 2 the same year, Notification of registry entry sent by post. December 4 the same year Forms received. Same month 4th, Entry of Kiku removed from registeration of the Takano family.

Eighteen months after Fusatarô's death, Kiku was re-entered into her own, Yokomizo family register and left the Takano family. In the meantime, she apparently made use of her Qingdao experience and worked at the Chinese embassy in Tokyo, where the Chinese minister resident, Li Shengduo (李盛鐸, his style, or courtesy-name was Li Shuwei, 李淑微) fell in love with her, and she remarried. Li was soon appointed to the Chinese Ambassador to Belgium, and she accompanied him Brussels. In Brussels she gave birth to their son Li Pang (李滂, his style was Li Shaowei, 李少微). The following year Li Shengduo's work sent him back to China, where the family is said to have lived for a while in Tianjin. Kiku then returned to Japan to look after her father and she died on January 22, 1914 in Japan, ten years after Fusatarô. She was 32 years old and 2 months when she died - even younger than him.

She had wanted to be buried in the Takano family grave, but Masu apparently prevented it. Later however, in response to Miyo's earnest request, Iwasaburô had her remains placed next to those of Fusatarô in the family grave. Fumi, the younger daughter of Fusatarô and Kiku, preceded her mother, dying on January 5, 1908. Having been born on January 18, 1903, it was a sad death, just before her fifth birthday. Miyo had lost her father, mother and sister and was an orphan, but she was taken in by Masu and Iwasaburô and raised as a member of the Takano family. In fact, in formal terms, as Fusatarô's daughter, now she was the head of the Takano household, and Iwasaburô's name was entered at the end of the register where 'Takano Miyo' was written, signifying that she had 'consented' to Iwasaburô's marriage.

In passing, it may be mentioned that Miyo's school education was at the Futsu-Eiwa High School for Girls (founded by Sisters of St.Paul of Chatres) in Kanda. There, strangely enough, she studied along with Katayama Sen's daughter Yasu. Several of the young researchers around Iwasaburô, especially Kushida Tamizô, were attracted to Miyo, but Iwasaburô saw to it that she was married to Harada Shôhei, an employee at the Kurashiki Spinning Company. She became a mother to one boy and two girls and led a happy life. If she were alive now, I do not think anyone would have welcomed the publication of this book more than her, but she died on May 5, 1967. The matriarch Masu was the healthiest member of the Takano family. Since losing her husband when she was 32, she had run an inn and then a students' lodging house, had brought up two boys, the younger of whom she had kept at his studies through to the postgraduate school of the Imperial University. Although Fusatarô had regularly sent home money from America, $10 a month was certainly not enough to support the Takano family household in Tokyo and to enable her younger son to aim for the highest level of Japanese education. To support the household, she therefore went on working as "a lodginghouse lady who takes good care of you". She continued to do this even after Iwasaburô became a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, so she must really have enjoyed taking care of people. She seems to have been liked and relied on by her lodginghouse students and by her son's friends and her relatives. She died on March 26, 1938 at the age of 89, a long life for those days.

What Fusatarô passed on to his brother Iwasaburô

Of those he left behind, Fusatarô's influence made its deepest mark on his brother Iwasaburô. Throughout his life Iwasaburô felt deep gratitude towards his brother and also a great debt. He always felt that his present circumstances were due to the past sacrifices his brother had made.

Iwasaburô understood his brother well and closely supported his endeavors, but pressed by his own cirumstances and his research, he could not render as much support as he would have liked. In June 1899 he embarked on a period of study abroad in Germany, with sponsorship from the Ministry of Education. His experience abroad, fortunate in many ways, could not have been more different from Fusatarô's years in America. He was able to immerse himself in his studies at the government's expense for nearly four years. It was in Munich that he met the love of his life and where he had his 'love nest'. During this period, his brother was defeated in the labor movement and left for China, from where he would never return. Iwasaburô's words "my brother was a failure" were filled with his own deep sense of remorse.

Throughout his life Iwasaburô continued to represent Fusatarô's principle that workers' own self-reliance was the only real path to the solution of their problems. For example, in 1907 in a paper titled 'The Factory Law and the Problem of Labor' (Kôjôhô to rôdô mondai), presented at the first conference of the Social Policy Association, Takano Iwasaburô argued that for a Factory Law to be effective, there should not be a government-appointed inspectorate but that workers themselves would have to superintend their own workplaces and for that, the formation of workers' combinations, in other words, labor unions, was indispensible. In the discussion that followed the main presentations at the conference, Kuwata Kumazô recalled the founding of the Social Policy Association, mentioned Fusatarô's name and made the following remarks, which the audience heard with evident emotion:

Professor Kuwata stood up and said "This Association has more than 100 members and is able to put on such a large conference as this at which so many are in attendance; when I recall the beginnings of the group I am overwhelmed with profound feelings. When the group was founded in 1896 at the Gyokusen in Kanda, we began by discussing the German Factory Laws. After the many vicissitudes of the intervening years we have arrived at our present situation. Thinking about all that, what come very strongly to my mind are the strenuous efforts exerted on the group's behalf by Professor Takano's late brother, Mr. Takano Fusatarô. If he were here today what could serve as suitable words of appreciation for him? Professor Takano has spoken of his gratitude to his brother and of his many recollections of him. All of us here have felt instinctively awed by what we have heard and will remember this for a long time.

Iawasaburô made his support for labor unions clear not only in academic meetings but in the labor movement itself. He was appointed a council member of Yûaikai (Friendly Society), the central organization of the pre-war Japanese labor movement which had followed on from Kiseikai. In 1914, with assistance from Yûaikai, he carried out 'a survey of 20 Tokyo workers' household finances'. He also submitted a proposal to the government for the legalization of labor unions. In 1918 he was appointed a member of the Home Affairs Ministry's survey team that was to investigate welfare enterprises, a body that had been set up as part of the government's prepartions to tackle social problems. The survey team strongly insisted that the government should take up the issue of labor unions and proposed the deletion of Article 17 Section 2 of the Public Order and Police Law. This was acknowledged by the survey team, as noted by Iwasaburô in his diary on March 2, 1919: "I feel that this is none other than revenge for my brother after 17 years." Article 17 of the Public Order and Police Law was not repealed for another seven years after this proposal, in 1926, but Iwasaburô's team's proposal was the stimulus that led to that final result.

Iwasaburô became the first Director of the Ohara Institute for Social Research, founded in 1919 and achieved many things in his lifetime. Among them was his editorship of the newly-created The Labor Yearbook of Japan (Nihon rôdô nenkan), first issued in 1920, which traced the origins of the Japanese labor movement. Publication was unavoidably interrupted around the time of World War II for some ten years, but in 2010 the Yearbook appeared in its 80th issue. The Ohara Institute for Social Research, which edits the Labor Yearbook of Japan, has for nine decades now been continually and systematically collecting materials that have constituted an archive without equal in Japanese labor studies.

Takano Iwasaburô the democrat

I would like to add one more observation about Takano Iwasaburô at this point. I wrote of Takano Fusatarô that this young man "born in the early Meiji period and educated in the years of 'civilization and enlightenment' (bunmei kaika) was a nationalist". Iwasaburô too was born at a time when Japan was still using the old calendar; he was of the same generation. But Iwasaburô, who witnessed his brother's hard struggle in close-up, as it were, broke out of nationalism and became a central figure in the liberal faction at the Law Faculty of Tokyo Imperial University. In the period of Taishô Democracy (1918-1926) he became a central figure in the ILO labor delegates issue and the whirlpool of the Morito Incident and in pre-war Japan he was one of the rare true democrats of the period.

After the war, Iwasaburô quickly grasped the importance of the constitution question and persuaded Suzuki Yasuzô and others to join him in forming a study group on the constitution question, which drew up a 'draft proposal for a new constitution'. In the process which led to the new constitution, the extensive influence which this group's proposals had on the thinking behind the composition of the GHQ proposal became widely known recently through the movie "Nihon no aozora" (The Blue Sky of Japan) (2007).

Besides his collaborative work on this draft proposal from the constitution study group, Iwasaburô penned his own personal proposal: "Personal Draft Proposal for the Constitution of the Republic of Japan". The fundamental principle set out at the beginning of the document reads as follows:

The imperial system is to be abolished and in its place a republican system instituted with a President as Head of State.

This proposal of Iwasaburo's did not garner much support even at the constitution study group. Even his pupils Morito Tatsuo and Ouchi Hyôe opposed it, and with the words "Even you say so Ouchi?" and a wry smile, Iwasaburô accepted the study group's decision.

Something else I would like to mention is Iwasaburô's affirmative stance on male-female equality, which was rare in the pre-war era. In 1925 he gave a lecture entitled "The Issue of Women's Employment in Japan" (Nihon ni okeru fujin no shokugyô mondai). In it he indicated that "the two great issues of our time are those relating to labor and women" and argued that equal pay for equal work, the right to participate in political life and equality of opportunity in education were all essential if the problem of women's rights was to be solved and that there was no other course but to undermine the deep-rooted and solid bastion of existing prejudice against such rights for women. This was not a lecture after the defeat in World War II; this was given over 80 years ago.

Fusatarô's resolve to become an economist

Besides support for the labor union movement, the other area in which Fusatarô infleunced his brother was in his will to become a researcher in economics. Takano Fusatarô showed a keen interest in economics from early on and even in the midst of his poverty-stricken life in America, whenever he had the opportunity, he would go and buy books on economics and study them assiduously. With such a zeal for economics, when Iwasaburô went up from the preparatory classes to the main classes of the First Higher Middle School [later renamed the First High School] and chose to focus on the study of politics, Fusatarô could hardly conceal his dissatisfaction and wrote to his younger brother:

I am not a little dissatisfied with your seeking to study politics at school.

Fusatarô wanted his brother to go on to study economics, not politics, but Iwasaburô opted to study politics at both the First High School and at The Imperial University. In fact, there was not yet an economics department at either of them. But when it came to choosing his specialist field, Iwasaburô deferred to his elder brother's wishes. His research theme at postgraduate school was "The Economics of the Industry with Special Reference to the Labor Problem". Ultimately, in order to keep Iwasaburô at the university, courses on statistics were instituted for the first time, and statistics became his speciality. But what is conspicuous about the statistical themes that Iwasaburô actually took up is that they focused on areas related to his brother's activities, such as surveys of workers' household budgets or surveys of cooperative unions.

In 1919 it was Takano Iwasaburô who advocated and achieved the independence of the economics department from the Law Faculty at Tokyo Imperial University. When this move for independence reached an impasse, Iwasaburô submitted his resignation to the President of the University and was able to achieve his goal by adopting such a resolute attitude. Most Japanese universities these days have an economics department, but the pioneer, the model for all such departments was the one at Tokyo Imperial University. To adopt the style of the ancient Chinese classics, one would say that Takano Fusatarô's ardent interest in economics brought about the creation of economics departments in universities throughout the land.

It was in this way that Fusatarô's will, through his brother Iwasaburô, lived on in Japan's labor movement, in labor studies research and in economics research. "Takano Fusatarô, may he rest in peace."

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), The last chapter 'Shippai no hito' ka ?

|