70 Years of the Ohara Institute for Social Research1 The Ôsaka PeriodFoundationThe Ôhara Institute for Social Research (OISR) was founded on February 9th, 1919. At the time, there were a number of academic research institutes in Japan in natural science fields such as the Infectious Diseases Research Institute (1892), the Ôhara Agricultural Research Institute (1914), the Kitasato Research Institute (1915), and the Physics Research Institute (1916), but the OISR was the first in the field of the social sciences.

Magosaburô, born in 1880 the second son of the Kurashiki entrepreneur Ôhara Kôshirô, was a public- spirited man. Under the influence of Ishii Jûji, the founder of the Okayama Orphanage, he had become a Christian and in accordance with Ishii's last wishes, he succeeded him as head of the Orphanage. From his experience as head of the Okayama Orphanage, Magosaburô gradually began to feel that there were limits to what was achievable in social enterprise work. He concluded that for the eradication of poverty there was a need for scientific study of social issues and for the clarification of policies to that end. It is believed that the reasons for these conclusions were due to the indirect influence of a friend from his elementary school days, Yamakawa Hitoshi and from his reading of Binbô Mnogatari (Tales of Poverty) by Kawakami Hajime.

In the founding of the OISR, the Ôsaka municipal authorities commissioned the participation of Ogawa Shigejirô,a well-known social entrepreneur, Kawata Jirô,a professor at Kyôto Imperial University, and Yoneda Shôtarôo, a lecturer at the same university, while advice was given by Tokutomi Sohô and Kawakami Hajime. However, an important role in determining the character of the Institute was played by Tôkyô Imperial University professor Takano Iwasaburô. Under Takano's leadership, Kushida Tamizô, Morito Tatsuo, Takada Shingo, Gonda Yasunosuke, Ôbayashi Sôji, Hosokawa Karoku, Kuruma Samezô, Toda Teizô became research Fellows, and studies were also commissioned from Ôuchi Hyôe, Kitazawa Shinjirô, and Hasegawa Nyozekan. That a newly-founded institute, and moreover one located in Ôsaka, a city not known for its scholastic achievements, should draw such talent was due mainly both to the attraction of working under the academic leadership of Takano and to Ôhara Magosaburô's financial support, but the effects of the 'Morito Incident' of 1920 ought not to be overlooked. 'The Morito Incident' occurred when professor Morito Tatsuo of the newly established Faculty of Economics at Tôkyô Imperial University published in the first issue (Jan.1920) of the economics department's journal Keizaigaku kenkyû (Economic Science Research) an essay titled 'Study on the Social Thought of Kropotkin'. The article was held by the authorities to be a violation of Article 42 of the Press Law of 1909 (treasonous defiance of the constitution), and both the author and the well-known editor, Professor Ôuchi Hyôe, were put on trial and found guilty. As a result, both professors were made to resign from Tôkyô Imperial University. Kushida, a lecturer at the same university, and Gonda and Hosokawa, both readers, strongly criticized the attitude of the professorial council during the affair and resigned from the university, successively joining the staff of the OISR. This array of talent attracted a number of young researchers: Uno Kôzô, Hayashi Kaname, Kawanishi Taichirô, Maruoka Gyô , Ueda Tamayo (Miyajirô Tamayo), Yamamura Takashi, Yagizawa Zenji were taken on as assistants. Changes in the System of Research

In the first years after its establishment the Institute underwent a series of major changes in its organizational structure. It is almost forgotten today but initially, there was a dual structure in place. In other words, the research institute associated with the name of Ôhara was not only a center for the study of social issues; it was also a research center for relief work. The Relief Work Research Center was founded three days after the Institute for Social Research, on February 12, the reasons for which remain unclear. Most likely, the Ôhara Relief Work Research Center was seen as a direct follow-on and development of the Aizen'en Relief Work Research Center, incorporating the ideas of Ogawa Shigejirô and others. However, plans to combine the two soon emerged, and in July 1919 the Institute for Social Research took over the Relief Work Research Center and became the Ôhara Institute for Social Research, with a dual structure, the one section focusing mainly on labor research and the other on the study of social work. This dual system came to an end in March 1920, after which, at first, it was decided that one part of the social work research section, the social welfare department headed by Terutoshi Yoshito, should be relocated as a research office to the Kurashiki Cotton Spinning Company's Manju Factory, where it would function as the 'factory insurance and welfare information office'. Not long afterwards, this factory insurance and welfare information office became completely independent of the OISR, and in July 1921 this led to the formal establishment of the Kurashiki Labor Science Research Institute, which, as is well-known, was the forerunner of today's Institute of Labor Science Research. FacilitiesAt first, the OISR offices were based temporarily in the relief work center of the Aizen kindergarten at Aizenbashi-nishizume, in Shimoderachô 4-chôme, Minami Ward, Oosaka. Library facilities made use of a room at the head office of the Kurashiki Cotton Spinning Company.

In May 1920, a year and a half after foundation, new offices were built at 24, Reijinchô in Osaka's Tennôji Ward, and the move there was completed by July. The new premises were a two-storey building of 673 sq. meters with a three-storey annexe (327 sq. m.) for storage of books and documents. The cost of construction was 150,000 yen. The main building consisted of a reading room, study rooms, an office, a filing room, an editing room, a source materials room, and a meeting room. Later, an additional three-floored storehouse annexe (535 sq. m.) and a two-floored lecture room (92 sq. m.) were added, making the whole an area of 1,627 sq. meters. The land measured 3,188 sq. meters and had been bought for 100,000 yen. An office was also opened in Tôkyô, where at first, Gonda Yasunosuke and Uno Kôzô worked, and then from the end of 1925, Kushida Tamizô. The Tôkyô office was first located in a room at the Statistics Association at 6, Yamashirochô in Kyôbashi ward. Several moves followed - from premises at the Dôjinsha Co. at 7, Surugadai Nishikôbaichô in Kanda ward to 122, Dôzaka in Hongô ward in July 1920 then back to Dôjinsha. On 26th January 1922 came another move, to 311, Ôkubô Hyakuninchô and finally, with Kushida Tamizô's job relocation, a second move back to Dôjinsha. People in charge at OISR

Those who advised Magosaburô at the time of the founding of the OISR were especially Professor Kawada Jirô of Kyôtô University, who was recommended by Tokutomi Sohô and Kawada's colleague, Yoneda Shôtarôo. The fact that the founding prospectus was written by Kawada (and one section by Yoneda) shows that staff from the Economics Department at Kyôtô University were at the center of the process that launched the Institute.

The OISR became the focal point of the progressive wing of the Economics Department of Tôkyô Imperial University. The effect of the Morito Affair contributed to the hardening tendency on the part of senior academics and education officials to regard research into socialist and labor issues as taboo. The OISR responded to this by becoming a real collection of researchers keen to engage positively with such issues and who pioneered an impressive body of work in various fields. In addition to research into Marxism, significant translations into Japanese under Director Takano's supervision of books by Sidney and Beatrice Webb - The Cooperative Movement in Great Britain (or The Decay of Capitalist Civilization?), The Consumer's Cooperative Movement - were important aids to Japanese scholars and activists for their understanding of the British labor movement with its long history. Besides these works, a series of vanguard studies in various fields was published such as Gonda Yasunosuke's studies of leisure activities based on social surveys, Takada Shingo's research into childhood issues, Hosokawa Karoku's study of the rice riots, Morito Tatsuo's studies of the early years of the Japanese socialist movement and of the women's movement. A little later, Kasa Shintarôo's work on inflation drew much attention. All these research results were published in Ôhara shakai mondai kenkyûjo sôsho (The OISR Research Bulletin), Ôhara shakai mondai kenkyûjo pamfuretto (The OISR Bulletin), and in Ôhara shakai mondai kenkyûjo zasshi (The Journal of the OISR), the first issue of which came out in 1923. The volumes of the Nihon rôdô nenkan (the Labor Yearbook of Japan), first published in 1920, provided valuable documentation of the activities of the labor union movement and of the labor movement in general, which was only just getting underway, and also of labor issues. 70 years later, the production of the Yearbook had become one the Institute's central tasks. Despite the interruption of the wartime and immediate post-war periods, the Institute has continued to edit and publish the Yearbook, providing a consistent and objective record of the path taken by Japan's labor movement.

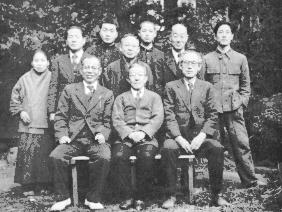

What made such activity possible has been the staff of the Institute's library and archive. Head librarians Morikawa Takao and Naitô Takeo as specialist library staff not only organized a huge archive of materials from Germany and England, which had been gathered by Kushida, Kuruma, and Morito, but Naitô also built up collections of materials relating to Japanese socialism and Marx/Engels in Japanese translation. Also worthy of note is the establishment of an archive room in 1923. Today, numerous research institutions have archive departments in additon to libraries. However, in the Japan of the early 1920s, the OISR was very likely in the van in this regard. 2 The Move to TôkyôOISR: to be or not to be....The first 10 years after its establishment were, so to say, the developmental period of the OISR, when it ploughed its own furrow as a research institution, opening up a series of new, previously unexplored fields of research. Under Takano's leadership, there were many ways in which the nature of the Institute - which, if anything, emphasized academic research - did not conform to what Ôhara Magosaburô hd been hoping for when he established the Institute: a combination of theory and proposals for practical policy. However, he stuck by his intention to "put up the money and keep my mouth shut" and left Takano in sole charge of the management. Nevertheless, with the Great Crash, the Depression and the consequent worsening of the economic conditions for the enterprises with which Magosaburô was connected, the number of those around him increased who urged him to drop the OISR, and he himself gradually inclined towards closing it. This intention surfaced in March 1928 at the time of the so-called '3.15 Incident', when the Institute was the subject of an investigation by the authorities. Takano and others strongly opposed the policy of closing the Institute, and for the next eight years negotiations went on between the two men over the issue of continuation or closure. Eventually, in July 1936, they agreed a) that the Institute should move to independent management in the future and relocate to Tôkyô, and b) that the costs of relocation should be borne by selling off the Institute's grounds and buildings. In February 1937, the OISR left Osaka and relocated to 896, Kashiwagi 4-chome, Yodobashi Ward (today, North Shinjuku in Shinjuku Ward). The property and buildings in Tennôji, together with part of the collection, were handed over to the Osaka City authorities. The Institute in Kashiwagi was housed in the former residence of Yamauchi Tamon, a famous painter in the Japanese style. It was a property of 1850 sq. m., of which the house itself occupied 500 sq.m., and was enlarged by the construction of a 250 sq. m. storage annexe. All this was about half the scale of the area occupied in Osaka. At the time of the relocation, many of the staff resigned, and just seven remained: Takano, Morito, Kuruma, Gotô, Naitô, Suzuki Kôichirô, Kimura Sadamu - a fifth of the personnel complement of the glory days of the 1920s. (The following illustration shows the staff during the Kashiwagi period: front row, from the left - Morito Tatsuo, Takano Iwasaburô, Kuruma Samezô, back row - Naitô Takeo, Sasai, Ôuchi Hyôe、Nagata Toshio, Gonda Yasunosuke, Kurada Shumpei.