2. The Tokyo Years

- The Young Head of the Family -

Tokyo in the early Meiji Period, 1877-1890

Tokyo, renamed from Edo, once a most flourishing city in the world with a population of 1.3 million at its peak, was a city in serious decline in the years after the Meiji Restoration. The inhabitants of Tokyo reduced to less than 600 thousands in 1873, owing to the decrease of the samurai population who had made up nearly a half of it, moved to their domain. Even 14,000 retainers of the former Tokugawa shogunate went to Shizuoka followed their lord. The samurai houses in Tokyo were virtually empty shells, only a few officials remaining to look after the properties. Many employees of the samurai families were now unemployed, and those merchants and artisans who had made their living from the samurai clientele were now out of business.

However, it did not take time to change the tide. New government rapidly increased its officials and employees', including job advertisements for 3,000 policemen, and people began to return to the capital to look for work. It was in 1876, later novelist Tayama Katai's father left Jôshû Tatebayashi to go up to Tokyo and apply for a job as a policeman and called on his son Rokuya (later Katai) to join him. Also many young people burning with a desire for knowledge and an ambition to get on in life were drawn to the capital. In 1872, Mori Shizuo, a doctor with the former Kamei clan domain in Tsuwano, Iwami Province, left for Tokyo with his eldest son Rintarô (later, Army Surgeon-general/author Mori Ôgai) . Five years later, Iyama Kentarô, who would become Takano Fusatarô's brother-in-law went up to Tokyo from Kyushû to study medicine. The Takano family's decision to move to Tokyo in that same year, 1877, might have been a consideration of their sons' education.

In Tokyo at that time many plans and projects were underway to present the capital as the symbol of 'civilization and enlightenment', and these too drew many people to the city. The population, which in 1873 had fallen to 570,000, saw a swift revival to 730,000 in 1878 in the inner city districts alone, and 1,050,000 if the outer districts are included. Two major projects proudly symbolic of 'civilization and enlightenment' were railway construction and the new 'brick-town' buildings along the Ginza promenade.

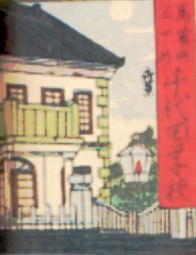

The railway had begun operating between Shinbashi and Yokohama in September 1872. A journey that previously had taken a whole day on foot or at its fastest, four hours by horse-drawn carriage, was now slashed to just 54 minutes. The construction of the Ginza 'brick-town' began in 1874 and was completed in June 1877. It was designed by a British architect Thomas Waters and consisted of a 14.5 m. wide roadway with 6.4 m. wide pavements on both sides laid along the 2.3 km stretch from Shinbashi to Kyôbashi. The entire length was paved, and two- or three-storied brick-built buildings with balconies were constructed on both sides of the avenue. People were amazed at the width of the street, which was double the size of the widest streets of those days, and were captivated by the sight of the gaslights which illuminated the area at night and the horse-drawn carriages and omnibuses which went up and down the road.

Both of these projects were designed to impress upon foreigners that Japan was a land of 'civilization and enlightenment'. Foreign travelers would arrive at Yokohama, take a train to Shinbashi and then make their way to the city center by carriage along the new 'brick-town' promenade. In 1882 horse-drawn trams went into service along the Ginza. Naturally enough, for Japanese too, Ginza, as a kind of foreign world in Japan, became the place to go when sightseeing in the capital.

Tayama Katai (Rokuya) recorded the following observations of the Tokyo of those days:

Rokuya was 11 years old and spent his days as an errand boy for the bookshop Yûrindô at Kyôbashi, running round Nihonbashi and Kyôbashi area. Tokyo in those days was a city of muddy streets, earthen buildings, government ministers' carriages and numerous street stalls congregating at the approaches to the main bridges. It seems like a dream world now. Outside Ginza area, the only western-style building was that the Keller Trading Company's at Sudachô, now the site of the Niroku Newspaper Company. It was a large building with three floors and on the roof there was a wind gauge with vanes that span round and round in the wind. Many sorts of foreign foods and other things were on sale there....

In the evenings, all kinds of food was available at street stalls. Sushi stalls, sweet bean soup stalls, hotchpotch and warm sake stalls, buckwheat noodle stalls, rice cake stalls - all those places stimulated my appetite as a boy. I relished such sights, though they are mostly no longer to be seen. I particularly thought so on cold winter nights and especially the buckwheat or wheat-wrapped pork dumplings that crowds of people used to stand in front of the stalls eating. The steam would rise from the pork in the bowls of rice, warming and satisfying. The men on those stalls sold those bowls of rice and pork so fast there seemed hardly time to wash the bowls. Around the west bridge-posts of Kyôbashi Bridge was something you cannot see anymore, not even in the suburbs: large basins of chopped meat from which the white steam drifted up, and the attractive smell of it caught the noses of the passers-by. Some very elegantly dressed people would stand and eat there and think nothing of it. There were many such food stalls around the bridge-posts of almost all the bridges. (Thirty Years in Tokyo [Tôkyô no sanjûnen] ).

Years of prosperity of Takano family

This mix of the old Edo and the new Tokyo was the city to which the Takano family had moved. Amidst the traditional pattern of building in the city, new-style buildings were now appearing one after another. Nevertheless, apart from the Ginza 'brick-town', the foreigners' residential quarter at Tsukiji, and some mixtures of western and Japanese style buildings such as government offices and schools here and there, Tokyo was still 'the city of water and bridges', 'the city of muddy roads' that it had been in the Edo Period.

The Takano family's first new address in Tokyo was No.8 Hashimotochô Block 3, Sub-ward 12 in No.1 Ward. This numerical form of address was soon abolished and renamed No.1, Kyûemonchô, Kanda Ward in 1878. Hashimotochô was notorious as the area of cheap inns for itinerant monks who went from house to house in their monks' robes, offering up prayers on people's behalf for money, so the change of the town's name was a plus for the Nagasakiya Inn, Takanos' new family business. The site, which covered 645㎡, was rented land. The family began its joint shipping agency and inn business there, trading under the name Nagasakiya. Its property consisted of two buildings, a two-storied wooden main building, of which the first floor covered 343㎡ and the second floor 193㎡, totalling 536㎡. There was also a two-story storehouse with thick mortar walls, each floor covered 33㎡. At 602㎡, this was quite a sizeable inn in the inner city area. It had a large garden, and Iwasaburô is said to have fallen into the pond and been rescued by a guest at the inn. It must have been a big pond for an elementary schoolboy to need rescuing from.

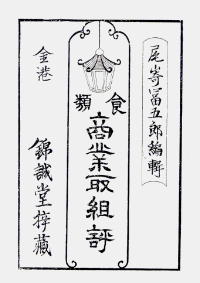

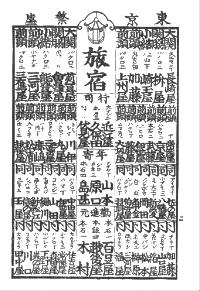

Although the family were newcomers to the inn business, Nagasakiya did surprisingly well. 'Evidence' of their success is found in the Restaurateurs' Business Ranking List edited by Ozaki Tomigorô. This booklet graded every kind of food and accommodation business in Tokyo. It ranked them all according to their reputations and listed them up so as to resemble a sumo ranking list. This booklet served as a kind of 'Michelin guide' of the Meiji Era and graded a total of 2,242 establishments in 38 kinds of business. 'Food-serving businesses' section that served some 23 different kinds of food, including set meals, haute cuisine, eel, sushi, and soup dishes and so on, and 15 types of 'Accommodation business section', which included inns, geisha houses, hot spring bathhouses and public baths.

Surprisingly, the inn page of the booklet places Nagasakiya as a sumo Champion (Ôzeki) of the East. There is no Grand Champion; the Eastern Champion is the top rank. I wondered "how on earth could an establishment that had only opened for business some two years before have become no.1 in Tokyo and I thought that perhaps it had been confused with the famous Nagasakiya that enjoyed the custom of the Chief Traders (kapitein) of the Dutch East India Company, but the address is clearly stated as Kyûemonchô. The inn used by the Chief Traders was in Nihonbashi Hongokuchô, and was well-known from the humorous saying that "the bell at Hongokuchô could be heard as far away as Holland". Ozaki, well-known for publishing guide books, was unlikely to have made a this kind of simple mistake here.

The most likely reason for Nagasakiya appearing as 'Champion' is good connections. The publisher Ozaki Tomigorô had lived in Yokohama since the opening of the town. He was the owner of Yokoama's leading publisher Kinkôdô, and also was a talented illustrator who had depicted "Illustrated Guide to Yokohama" (Yokohama Annai Ezu). It is thought that about the same time, the brothers of Fusatarô's father, Takano Kame'emon and Yasaburô, who were running inns in Yokohama and operating shipping agencies, sold the Nagasakiya. Nevertheless, however much good connections may have secured the high placing on the match list, if the inn had not actually been doing good business, it would not have received such a good placing. In the high class restaurants group the the East and West Champions are the famous establishments Isegen and Yaozen, so Nagasakiya's high ranking seems to have been no mistake.

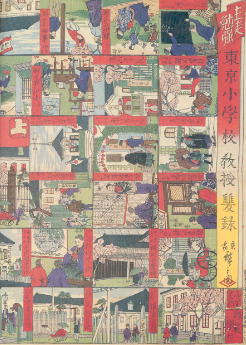

Elementary schoolboy in Tokyo

The first school the Takano brothers attended in Tokyo was the Chiyoda School. An illustration of the Chiyoda School of that time by Hiroshige Ⅲ was included in the pachisi 'Elementary Schools in Tokyo'. With its circular columns at the entrance, a balcony above, the gate lit by a gaslight, it looks to be clearly a copy of the western-style brick buildings on the Ginza. The school is doubtless shown at night so as to include the gaslight and the moon, an unusual feature for a school in those days.

It was a school on a grand scale 430㎡ of buildings on 2,435㎡ of land, but had only a short life, as it was destroyed by fire only four years after construction. Nevertheless, a picture of what it looked like has survived from a board game.

The Chiyoda School was located at Block 3 Bakuro-chô right in front of Nagasakiya and was built on the site of the Hatsune riding ground in the Edo period. The area was known as the place where the Tokugawas assembled their cavalry before the Battle of Sekigahara, and the school was built with donations raised on 29 towns in Nihonbashi-Kanda area. The school was formally opened on March 20th, 1877, and lessons began on April 1st. It was as if everything had been timed just right for the Takano brothers.

There had been a pivate terakoya school Kôgakudô run by Chiyoda Nobuyasu. Kôgakudô had founded in 1870, at Kodenma Uemachi, where Chiyoda had mainly taught calligraphy. Following the enactment of the First National Plan for Education (Gakusei) he trained to be an qualified elementary school teacher, and went on to teach arithmetic, geography and physics. He also opened a night school, this was no doubt because most of his pupils were shop boys and apprentices working for shops in the district. Night classes went on after the establishment of Chiyoda School; hence the gaslight was drawn in the pachisi.

At that time, the elementary schools run by the local authorities in Tokyo usually had about 200 pupils and four or five teachers. Almost all teachers were male; there were no more than 20 female teachers in all the public schools in Tokyo. Most schools, including Chiyoda School, were co-educational. The gender balance varied from school to school, but on the whole, there tended to be one girl for every two or three boys.

What did the Takano brothers study at Chiyoda School? Uchida Roan has left us an account of his studies which helps to answer this question. Uchida was born in the same year as Fusatarô and described the school life of that time in a text titled "Elementary school in the late 1870s". In passing, it may be mentioned that young Roan attended Matsumae School in Mukôyanagihara, which was no more than 20 minutes' walk from Fusatarô's home. The regime at Matsumae School would not have been very different from that at Chiyoda School.

I believe that I entered Matsumae school in 1874. The first thing we studied was Sekai Kunizukushi (All the countries of the world, for children written in verse) by Fukuzawa Yukichi. I had been taught Chinese classics and Tang Period poetry at home, so 'All the countries of the world..'. made little sense to me, but I liked the way Fukuzawa wrote so I used to recite it along with songs of the candy seller. It was about a year later that All the countries of the world... was replaced by a translation of a reader by Wilson. At that time most elementary school textbooks were translations of western textbooks, so unlike those of today, they were international, and we were taught about history and science through the use of such readers. The Bible was often cited in western textbooks at that time, so we, who were taught using those translated readers, soon got familiar with the names and stories of Moses, Abraham, Solomon, and Samson. As a result, people educated in those days had a great interest in the world compared with today's elementary school pupils.

Fukuzawa Yukichi's Sekai Kunizukushi (All the countries of the world) was a set of six volumes, written as a children's textbook in Japanese orthography. It was the 'international' version of the terakoya textbook Kunizukushi (All the countries in Japan) that had been used in Edo period. It was no mere geography textbook but was written in large script so as to double as a model of good calligraphy. Fukuzawa's method was to arrange basic knowledge about the geography of the world and about each country under 75 headings, which came with 6 separately bound appendices for teachers with detailed notes and information.

As Roan writes, that was the period in which elementary school texts were almost all translations of western books, and the translation of the reader by Wilson to which he refers was a direct translation of an American textbook. It was called a Elementary School Reader (Shôgaku-tokuhon) and was the most commonly used of all elementary school textbooks, but it is hard to comprehend why such a poor piece of work, a crude word to word translation, was so widely employed. For example, chapter 1 of Vol. 2 reads:

This little girl has a doll.

Do you see the doll?

This doll is a cute doll.

Do you like dolls?

Yes, I like dolls very much.

Such was the strange mixture of the old terakoya school and the new era of 'civilization and enlightenment' soon after the beginning of the elementary school education system. Nevertheless, the education of that time was internationally aware and certainly did orient the eyes of schoolchildren towards countries overseas.

The death of his father

The 'Michelin Guide in Meiji Tokyo', Nagasakiya may have been feted as the 'Champion' of the inn section, but just at that time, the Takano family was plunged into sadness by the death of the father, Senkichi, on Aug. 26th, 1879 at the age of only 34. He left behind a family of five: his mother Kane (70 years old), his wife Masu (32), his eldest daughter Kiwa (13), his elder son Fusatarô (10) and his younger son Iwasaburô (7).

With Takano Senkichi's death, Fusatarô became the head of the Takano family and at the same time, owner of Nagasakiya. Licenses had to be procured for the inn and shipping agency businesses, and after his father's death, all such licenses bore Fusatarô's name. In the record book of important Takano family matters (Yôyôbo), there are copies of applications made to the local Ward Office and the police station as well as to the Mitsubishi Company. He also became a guarantor of a student who was staying at Nagasakiya. There is a copy of a guarantee addressed to the Office of the Medical Faculty of the Tokyo University signed by Takano Fusatarô, who was then still a minor, and who, on behalf of the student who had no sponsor, stated that I shall ensure his compliance with university regulations and I hereby undertake to be responsible for him.

Fusatarô was only 10 years and 7 months old when his father died, so although he was now the head of the family, he was no more than the nominal boss of Nagasakiya. Both roles were almost certainly taken on by his mother, Masu. With an elderly mother-in-law and three young children to support, managing the Nagasakiya must have been hard work.

For Fusatarô, however, becoming the head of the household completely changed his life. Wherever he was for the rest of his life, Fusatarô was made to feel the responsibility of being the head of the Takano family. When he himself wanted to forget this, those around him would not allow it. His uncle Yasaburô, his mother Masu, his sister Kiwa all had strong expectations of Fusatarô, and his brother Iwasaburô also depended on him. I shall touch on this question of the burden of family responsibility again from time to time, but if he had not been placed in this situation, his life would certainly have been different. And yet, it seems that Fusatarô did not actually feel the responsibility as such a heavy burden, and had no qualms in seeking to fulfil the expectations of those around him. He had suffered little in life up to that point, had grown up happily as the eldest son of a wealthy family and had been successful in his school studies. With such a background, Fusatarô would have felt that success was not hard to come by.

The Nagasakiya Fire

Just a year and a half after the death of his father, young Fusatarô's family was rocked by another bitter blow. In the great Kanda Matsuedachô Fire of Jan. 26th, 1881, Nagasakiya was burned down. The fire broke out just after 2.30 a.m. that night at a susa shop in Kanda Matsuedachô some 500-600 meter to the west of Kyûemonchô. Someone had set fire to a large pile of straw between the susa shop and the neighboring rice shop. Susa, was a traditional material mixed with earth and used for rendering and preventing cracks in wall plaster. Cut rice straw was used for rendering rough-coated walls, and hemp and paper were used for the top coat. In recent years earthen walls are almost never plastered, so susa shops have surrendered to the changing times. Such shops can no longer be found in Yellow Pages. But in Tokyo in the 1870s and 80s, earthen buildings and earthen plastered walls were the fashion, so there were specialist trades catering for them.

A policeman who happened to be passing by the house of Shiozaki Kunijirô at No. 22 Matsuedachô discovered the fire and alerted the neighborhood, which did its best to fight the blaze but to no avail. The dry winter weather had made the straw extremely flammable, and blown by the prevailing northwest wind, the fire grew, and there was little that could be done to stop it. Leaping here and there, it even crossed the Sumida River and spread further. The conflagration raged for 16 hours and by its end had burned out 11,000 houses across 108 blocks in 4 wards: 21 blocks in Kanda Ward, 27 blocks in Nihonbashi Ward, 50 blocks in Honjo Ward, and 10 blocks in Fukagawa Ward. Kyûemonchô was in the wind's path, so the only thing to be done was run for one's life.

A policeman who happened to be passing by the house of Shiozaki Kunijirô at No. 22 Matsuedachô discovered the fire and alerted the neighborhood, which did its best to fight the blaze but to no avail. The dry winter weather had made the straw extremely flammable, and blown by the prevailing northwest wind, the fire grew, and there was little that could be done to stop it. Leaping here and there, it even crossed the Sumida River and spread further. The conflagration raged for 16 hours and by its end had burned out 11,000 houses across 108 blocks in 4 wards: 21 blocks in Kanda Ward, 27 blocks in Nihonbashi Ward, 50 blocks in Honjo Ward, and 10 blocks in Fukagawa Ward. Kyûemonchô was in the wind's path, so the only thing to be done was run for one's life.

There was quite a distance from the location of the fire to Nagasakiya, so there was plenty of time to carry valuable goods to the earthen storehouse and seal up windows and doors. However, perhaps due to the power of the blaze or because the storehouse was not solidly built enough, it too burned and collapsed. The neighboring Chiyoda School was also destroyed, and Nagasakiya, which at 602 ㎡ was 165 ㎡ larger than the school, was burned to the ground.

Takano Iwasaburô later wrote about the fire: "The house burned, the storehouse collapsed, and the four of us ran out into the street without a stitch on us". After the fire, the family moved to 2-4, Koamichô, in Nihonbashi Ward, and in November that year they acquired a two-story house, almost 200 ㎡, in Naniwachô, Nihonbashi Ward and moved in. They also received from the Mitsubishi Company as an insurance repayment of 100 yen and interest of 17 yen 50 sen, with which they started up the inn business again. They also still owned the land of their house in Nagasaki and land in the surrounding countryside. Iwasaburô's words in his memoir "We ran out into the street without a stitch on us" might be a literary expression but it does not correspond to the facts.

Behind the very dry account in the record book of important Takano family matters (Yôyôbo) after the fire is the stout-hearted figure of Masu. After marrying her husband and leaving the place where her ancestors had lived for generations, the family business had just begun to go well when she was widowed and immediately after that, her inn, which had been judged among the best in the Tokyo, was burned down. With three children to support, most people in her circumstances would have been at their wits' end, but Masu was not defeated by these hardships. She acquired a new house and property and within ten months she had reopened Nagasakiya. In this achievement she was aided by Nagasakiya's reputation as one of Tokyo's best inns at its former site in Kyûemonchô and also by her own strength of character and leadership qualities. Masu's capacities were evident in the reopened inn, where in 1882, 2,623 guests were accommodated during the year, and an average of seven guests a night stayed in the inn's six rooms. One can well imagine it must have been hard work.

The district that included Naniwachô had been the place of Yoshiwara, the famous red light quarter of Edo until the Great Fire of Meireki (Furisode Fire) and was known as Moto Yoshiwara (Ex-Yoshiwara). The neighborhood had for several centuries been known for its theaters; right in front of Nagasakiya was Hisamatsuza, the later Meijiza. The Takano family had moved to what during the Edo Period was Japan's largest street of entertainment. There were no more brothels of course, and Hisamatsuza had burned down, but many theater people still lived in the surrounding area; it was a lively, bustling place. The fact that Takano Iwasaburô, who often looked the very image of seriousness and austerity, was later remembered that he frequently went to the theater with his mother, and liked women's gidayû songs and when he had free time he loved to listen to the delicate songs of Roshô and Sanchô was no doubt due to his childhood experiences living in that area.

Education mama Takano Masu

Fusatarô, who had graduated from Chiyoda School, went on to study at the at Kôtô Higher Elementary School in Ekôin, Honjo Ward where he also graduated. Well known novelist Akutagawa Ryûnosuke too graduated from this school. The month Fusatarô changed school is unknown but it was in 1878. Here, however, there is another conundrum. Why did he not go to school in Kanda Ward, where his home was, and why did he not go on to a higher school in Nihonbashi Ward, which was part of the same ward as Kanda at certain time? Certainly, the Kôtô School was not far from his home in Kyûemonchô. Once over the Ryôgoku-bashi Bridge, one is soon in Ekôin, so even a child could get there in 15 to 20 minutes. The problem is that not only Fusatarô but his brother Iwasaburô also went on to, and graduated from, Kôtô School. It was a 40 or 50 minute walk from there to Naniwachô, a distance that was quite normal for people to walk in those days. Nevertheless, with the Hisamatsu and Arima Schools, which both had their own Higher Elementary Schools, so close to home, why go all the way to the Kôtô School? The main reason was probably the high estimation of the standard of teaching at the Kôtô School. The History of Honjo Ward contains the following statement in the section 'History of the Kôtô Elementary School':

November 1886, His Imperial Highness Crown Prince Yoshihito graced the high-achieving school with an official visit.

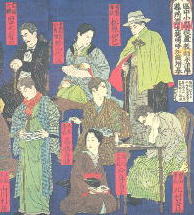

A particular woodblock color print provides further strong evidence of the school's high level of education. It shows people active in the field of education in Tokyo at the time and was made in 1877. Alongside Education Minister Tanaka Fujimaro, women's education pioneer Atomi Kakei, and Fukuzawa Yukichi, promoter of western studies, is the figure of "Yamakawa Toshinari, Kôtô School". Yamakawa was the Principal of Kôtô School and was regarded as an outstanding talent in the field of elementary education.

Another reason why the Kôtô School was so renowned for its excellent results was likely to have been due to the fact that it was an all-boys' school. In those days, most elementary schools in Tokyo were coeducational, but just before Fusatarô entered the school, it created a separate establishment for girls and became a school with separate teaching provision for boys and girls. The school's academic results rose accordingly. Most people felt at the time that 'girls don't need to study'. This is clear from any examination of school attendance statistics. In 1879 the national average was boys: 58.21% and girls 22.59%. In general, girls' desire to study was less than boys'; Uchida Roan describes the atmosphere at his own coeducational higher elementary school:

I was the only boy in my class; I really felt at a loss because the rest were all girls. Although it was called a elementary school - higher elementary school today - in those days when girls graduated from elementary school or did not graduate because they were due to marry, they were at an age when they were preparing for marriage and acted like adults; they treated pupils like me, who were younger, like children and completely ignored us. Even if the girls couldn't get good results the young teachers would greatly indulge them whereas I, who got the best grades, was ignored and hardly visible. When I left that unpleasant school and went back to my old one, my old teachers and classmates, I felt most relieved. (Meiji jûnen zengo no shôgakkô [Elementary Schools in the Late 1870s])

The fact that the Takano brothers did not go to a school nearby but went all the way to Kôtô School was no doubt due to their mother Masu and her 'education mama' attitude. Many young men who burned with ambition to get on in life stayed at Nagasakiya. She observed these youngsters closely and would have keenly perceived that education had the power to change one's prospects in life. In 1881, the year when the family was burned out in the great fire, Fusatarô completed his Higher Elementary School studies. Iwasaburô wrote in My Brother Takano Fusatarô:

My brother moved from Chiyoda Elementary School in Asakusabashi to the Kôtô Elementary School where he graduated in 1881. There were five or six others in his class.

Iwasaburô graduated a few years later from the same school, so his memory of his brother's graduation year is likely to be accurate. Also, in the record book of important Takano family matters (Yôyôbo) records that the name of the owner of the family's property and the person in whose name the family business was conducted changed from Senkichi to Fusatarô in Nov.-Dec. 1881. This amounts to further evidence of Fusatarô's graduation in 1881.

What Iwasaburô meant by 'five or six others in his class' was most likely the number of Fusatarô's fellow graduates. The fact that six pupils graduated at the same time was itself proof of the high level of education at the Kôtô School. Graduating from higher elementary school in those days was a far more significant step in a pupil's life than we imagine it to be today.

As I mentioned earlier, the system in those days was that pupils moved up a grade only after success in the half-yearly examinations. Those examinations were extremely tough. The Ministry of Education enforced the following rules in every city and prefecture : Pupils' advancement is to be rigorously controlled...No easy or temporizing advancement is to be tolerated. The strictness of this advancement system is evidenced by the record of the number of registered pupils at each grade level. In 1878, when Fusatarô entered junior high school, in the urban district of Kyôto there was a total of 59,193 registered pupils in elementary and higher elementary schools (shôgakko ); of these only 394 were registered in higher schools, a mere 0.67%.

To graduate from both elementary and higher elementary school, one had to pass the 'big examination' (daishiken). Graduating from higher elementary school meant one would have taken 16 examinations since entering elementary school. Teachers from teacher training schools were specially appointed to serve as 'examination committee members', charged with supervising the 'big examination', and several schools carried out the examinations together at the same location. The examinations in 22 subjects were held at a nearby teacher training school for four days from morning to evening. On examination days, there were present not only the invigilators but also city or prefectural officials, a principal of the teacher training school, heads of families and school district officials; fathers and brothers were also allowed to be present. Oral examinations were carried out with a pupil almost surrounded by adults.

Earlier, I mentioned that Fusatarô was 'an excellent pupil at school'; the basis for supposing this was the discipline of the school system he had experienced.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai, (Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), Chapter 2 Wakaki koshu - Tokyo jidai

|