7 A Sailor with the US Navy

- posing as a war correspondent -

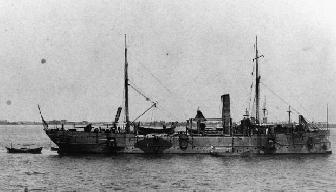

A mess attendant on the gunboat Machias

Fusatarô was ordered to report to the USS Machias on Oct. 1, 1894. The gunboat had been laid down at the Bath Iron Works, Maine in 1891 and commissioned in 1893. Gunboats of the period were small, shallow draft vessels, armed with cannon, that were capable of navigating canals and rivers. The ship's name hailed from the first naval battle in the history of the United States, which took place off Machias, Maine.

The ship was 62.48m (204 ft) long, 9.78m (32 ft 1 in) at its widest, draft 4.3 m (14 ft) and had a displacement of 1177 tons. It was a schooner-rigged gunboat, powered by a 2200 hp steam engine driving twin propeller shafts and was also fitted with sails. Armed with eight guns, though only a small vessel, it was a size larger than the Kanrin Maru [Japan's first modern warship, powered by sail, steam and screw - transl.] which crossed the Pacific in 1860 and which was just 49.7m in length and 7.3m wide.

For almost a year after its commissioning the Machias patrolled north Atlantic waters, but in September 1894 it was ordered to refit for service on the US Asiatic Squadron. Its duties were to safeguard US interests in the northeast Asian region that was the scene of the most action in the Sino-Japanese war. However, the US Navy did not appear to regard the situation in Asia as 'critical' for US interests, which can only be surmised from the fact that it was not until one and half months after the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War that the US Navy ordered ships to East Asia, and not from the west coast, from where they could have sailed directly, but from stations on the east coast. Furthermore, it was more than two months after the issuance of the ships' orders before they left port. Few of the ships' crew members can have felt any of the tension normally associated with sailing to a war zone.

With its complement of 147 - 11 officers and 136 other ranks - the Machias was commanded by E.S. Houston, Commander US Navy. The officers included the captain, four other officers on the bridge, three in the engine-room, the ship's engineer, the paymaster, and the ship's doctor. There were supposed to be 78 sailors, but the actual complement was 85; in the engine room there were 29 men instead of the stipulated 28. In the technical department there were five, in the special department six and in the mess, eleven. All the mess staff were Japanese. The chief cook was William Yamaguchi and the cook Esso Hyûga. The head waiter was Kisaburô Iwamoto and the rest, including Fusatarô, were all 'mess attendants' i.e. waiters. They most likely also worked in the kitchen.

On Nov. 20 the gunboat USS Machias left the Brooklyn Navy Yard in New York, bound for East Asian waters. The Panama Canal would not be open for another twenty years, so the route taken to the Pacific was the long one across the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea, across the Indian Ocean, through the Moluccan Straits and past Singapore. It was three and half months before the Machias put in at its first destination, Hong Kong, on March 6, 1895. The long trip from west to east - two thirds of the way round the globe - had taken 108 days sailing, and from north to south, the ship had traveled from New York at latitude 40°N down to Singapore which was almost at the equator and then back up to northeast Asian waters between latitudes 30-40°N. With its eight guns and light draft that enabled it to navigate canals and rivers, the gunboat made only slow progress across the oceans. The ship's log contained the following entries regarding the ports of call and periods of stay during the voyage.

Dec. 2-4 San Miguel island, Azores [volcanic island in the Atlantic]

Dec 9-18 Gibraltar

Dec 22-27 Malta

Dec 31 - Jan.16 Port Said [entry to the Suez Canal]

Jan. 16-21 Aden

Jan. 30 - Feb. 8 Colombo, Ceylon [the capital of today's Republic of Sri Lanka]

Feb. 16 - 26 Singapore

Although the sun was setting on Great Britain in these years, her maritime empire was still strong, and all the ports at which the Machias put in, with the exception of the Azores, which belonged to Portugal, were British colonial possessions. Each stay lasted about a week, long enough to take on water and coal; this had to be loaded manually, which took time. Even during the longer stays the crew were not allowed on land at their leisure. Fusatarô would not have been able to see as much as he no doubt would have wanted. Card games were popular with the Japanese crew members, and Fusatarô frequently lost out in these games. He later recorded in his diary that he would never gamble at cards again.

After her arrival at Hong Kong, the Machias did not promptly proceed to its duties. Following its long trip, the ship had to put in for repairs for two weeks from March 15 at the Kowloon docks. Leaving Hong Kong on March 28, she proceeded to Amoy [today, Xiamen on the east coast of China] and from there, was finally able to take up her duties patrolling in northeast Asian waters.

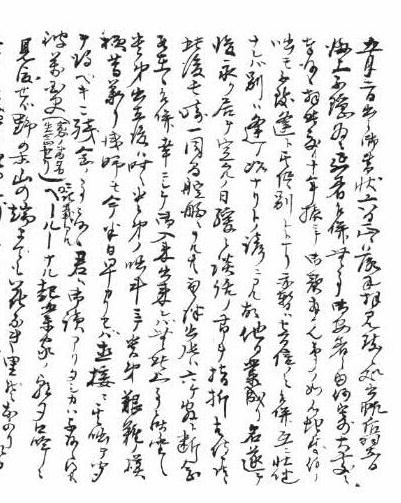

Reproaches and encouragement from his sister and her husband

After reaching Amoy on March 30, 1895, the USS Machias headed for its next port of call, Nagasaki, three weeks later on April 21. On seeing his hometown again after 18 years, a complex of emotions must have welled up inside Fusatarô. The Machias put in at Nagasaki from April 25-27, just two days. During this time, he was able to meet his sister Kiwa and her husband Iyama Kentarô again, whom he had not seen for ten years; they came from Karatsu for the meeting. We know of this meeting from a letter Kiwa sent shortly afterwards to care of the American consulate at Zhifu [now Yantai], China. It is an important letter because it not only lets us know about the meeting itself but also enables us to see how Kiwa and her husband regarded Fusatarô at that time. I shall therefore reproduce a section of it:

Your letter of May 2 was delivered on the 6th. The sea was very rough the day after your ship left, so I was very glad to read that, although delayed, you arrived safely. Seeing your face again after ten years was like a dream, and it is a pity that we could not talk for very long and had to part so soon after meeting and now have to return to writing letters for a while.

But, as the saying goes, 'in every parting is the seed of reunion', so if we both remain in good health, we shall surely meet again. I am waiting and counting the days to the time when your enterprises are successful, your name renowned, you are living again permanently in Japan and we shall be able to meet again. I realize that even if your ship comes to Nagasaki for a week it will be difficult for you to come here to Karatsu, but if you were able to come, I would be very happy.

After you left, we talked of nothing but you for some time. When I heard about what hard and bitter experiences you have had, I was sorry I had not arrived half a day earlier in Nagasaki to hear from you directly. I don't know if you have read it, but in that book, the History of the World (I don't recall the actual title) there is a poem by the entrepreneur Pêrû that he used to recite morning and evening:

When one looks around, there are flowers everywhere

nowhere is without them;

all are in full bloom, fragrant and beauteous

but when one thinks of how they came to be,

it was not without pain and suffering

[The book might be a translation of Peter Parley's universal history, on the basis of geography(1837). This American textbook translated into Japanese in many editions as "Bankokushi" or " Pârê Bankokushi" or "Bankokushi tyokuyaku". At least 15 different publishing firms published the book in Japanese or interlinear translation in the 1870s-80s. One of the most well-read book in Meiji Japan. However I have not been able to identify the citation so far.]

As in that poem, the hard life you have led will be followed by a happy spring to which you can look forward. You owe your health to our parents. To work so hard in place of your father for the sake of your dear brother, to go on like that for seven or eight years for the sake of filial piety and for the feelings you have towards your brother is something I could not possibly match. You have behaved so uprightly and with such filial piety that I pray for the day when your endeavors will prosper and you will succeed in restoring the family name. Please go on striving hard for that day!

This success is not only in the future; you have already achieved part of it, by which of course I mean that Iwasaburô has turned 23 years old and has not failed once in his studies; soon will come the glorious day of his graduation. Our mother has done her duty as a woman and has raised Iwasaburô with great love and care. Everyone who visits them comes away impressed by the depth of her love for him....

Today, we finally embarked on the S.S. Matsuura and returned home. As for your request with regard to gifts, it has been dealt with in the following manner. You do not need to return the money outstanding.

* I yen 13 sen Samonchô (kimono material)

* 1 yen 13 sen Yasakachô (kimono material)

* 55 sen mother at Araoya

* 3 yen 60 sen Ôtsu Reizô (kimono material)

* 7 yen 90 sen Fujioka (kimono material)

* 2 yen 20 sen Iyama (bag)

* 15 sen Tokyo Telegraph Company

* 40 sen Tokyo exchange rate commission

* 30 yen Tokyo remittances

* 28 sen silver exchange brokers' refund

The matter has already been more or less settled, so an amount of about 1 yen 50 sen would be sufficient next visit. I have heard that a lot of fruit is available at Zhifu [today, Yantai], at 3 or 4 sen a basket, so please buy apples or grapes. It's your homeland so a lot of people might be talking about you there. It would be worthwhile buying some pieces of coral should you find any. Please bring a gift for aunt Otomi too.

Thank you for the gold ring. I've become quite an expert on them thanks to you.

It's getting quite hot now so please take you care you don't doze on deck.

May 11

Iyama Kiwa

Takano Fusatarô Esq.

It would seem that whereas Iyama Kentarô arrived earlier in Nagasaki than Kiwa and exchanged ten years of news with Fusatarô, his wife Kiwa, although she did meet her brother, was not able to share much time with him. When she learned that although he had been away from home for so long, he had not prepared any presents for his relatives in Nagasaki, she received $50 from him, bought the presents and distributed them to the relatives on his behalf.

When I first read the letter which gracefully brushed calligraphy in sumie ink on rolled paper, I was struck by her fine writing ability, unusual for a woman of that period and her citing a quote from a foreign book translated into Japanese. I was interested to see that, as might be expected in a sister of the well-educated Takano brothers, she too had clearly received a good education. But as I read it several times over, I began to realize that the letter in fact had been written by her husband Kentarô. The style and sentence structure are not those of a woman of the period. Apart from the section about the presents, the rest is strongly colored by Kentarô's ideas. The letter urges Fusatarô in a reproachful manner to quit his lowly labors and improve his standing in the world, expecting that he will apply himself to restoring the family name and fortunes: Please go on striving hard for that day! While it praises Fusatarô for his contribution to his brother's approaching university graduation, it considers it only natural that, as head of the family, he should have played this role.

While the Iyamas highly esteem Iwasaburô's efforts in studying at the Imperial University, they do not conceal their dissatisfaction with Fusatarô's situation. The letter gives no indication at all of whether they knew or did not know of his having learned English in America, his studies of labor issues and his writing English articles for the American Federationist. They must surely have known at least of his page-long reports for the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, but the letter does not refer to that part of Fusatarô's life either. Instead, it focuses on the need for him to move on from his 'wretched' work as a US sailor and strongly expects that he will return to the business world and restore the family's good name as soon as possible. That his sister and her husband were dissatisfied with him and constantly compared him to his brother greatly oppressed Fusatarô.

If Fusatarô had opted to use a warship simply as a means of enabling him to get home for free, he would surely have absconded during the ship's first call at Nagasaki yet he went on working as a navy sailor for over a year. This was no doubt because his pay had not yet been sufficient to enable him to repay his debts. It is likely that he also wished to use this opportunity to get a good view of other countries in Asia.

China patrol

On leaving Nagasaki the Machias headed for Zhifu [today, Yantai]. She was delayed by strong winds, but made port safely on May 1 and remained there for two weeks. Zhifu is located on the northern side of the Shandong peninsula and was one of the several traditional stopover points on the route between Japan and China for ships regularly plying between Pusan, Jinsen [today, Incheon] Yokohama and Shanghai. Another reason for Zhifu's importance was the location there of a US consulate. On May 5, a week after the USS Machias arrived, Zhifu was also the location for the exchange of ratifications of the peace treaty between Japan and China, which ended the Sino-Japanese war. It is possible that Machias put in at Zhifu in order to gather information related to this event. For the following four months, based at Zhifu, the Machias continued her coastal patrol in the Yellow Sea and the Bohai Sea off Ryojun, Taku [near Tianjin] and Qingdao. This region was the area of operations in both the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars and was regarded as important geopolitically. The Machias was of course not constantly on patrol; she would put in at Zhifu from time to time to take on supplies and on such occasions, would be in port for between one and three weeks.

From mid-August 1895 the focus of the Machias' patrols was switched to the the Yangtze River delta area, no doubt because in the high water season navigating the river would have been much easier. She left Zhifu on August 19 and on the 23rd arrived at Shanghai at the mouth of the Yangtze River. Then as now, the largest city in China, Shanghai was the location of the joint US-UK Settlement and the French Concession, and the Powers were continually competing with each other to maintain and expand their interests in their settlements. After spending more than a month in Shanghai, the Machias left the city on Sept. 24 and headed up the Yangtze River, stopping off at the main cities en route such as Zhenjiang, Nanjing as well as Lake Poyang and arriving at Hankou on Oct. 3.

Gunboats were warships built to navigate the shallow waters of rivers, and if necessary, the Machias could have continued up the Yangtze as far as Yichang and Chongqing, but she did not proceed further up-river than Wuhan. Nanjing and Wuhan are known for their great heat and humidity in summer, and along with Chongqing are called 'the three great ovens of China'. They must have still been very humid at the end of September, which is perhaps why, four days after arriving at Wuhan, the Machias began to head back down the Yangtze and arrived back at Shanghai on Oct. 15, her three month 'Yangtze patrol' at an end. There she docked for over 40 days until late November.

English article: 'Chinese Tailors' Strike in Shanghai'

The crew on Fusatarô's ship must have had some time to themselves. Fusatarô pressed on with the writing of a Japanese-English dictionary which he intended to have published after his eventual return to Japan. We know that he submitted four articles written in English to Japanese and American magazines. The first of these was titled 'The War and Labor in Japan'. It was sent on May 10 to the Social Economist, which was edited by George Gunton, and published in the July 1895 issue of the journal. In June he sent 'The Japanese Workers' Condition' to the official journal of the AFL, the American Federationist. To the same journal, he sent an article titled 'Chinese Tailors' Strike in Shanghai', based on his experience of Shanghai. He also sent a piece titled 'Labor Problem in Japan' as an addendum to 'a contribution from a warship' to the monthly magazine Taiyô (Sun) published by Hakubunkan.

The most interesting of these are the first and third, 'The War and Labor in Japan' and 'Chinese Tailors' Strike in Shanghai'. The first discusses the effects of the Sino-Japanese War on the Japanese labor scene. In it he predicts that the fact that the wages paid to Japanese workers working in the war zone were usually four to five times higher than the norm would have a subsequent positive influence on labor issues and the labor movement. The article follows the line of Gunton's theories that higher wages would bring in train demands for an increased standard of living. He points out that this could at first benefit only one group of workers at a particular time but that the improvement in their livelihood would plant a seed of desire in the hearts of the workers which would one day blossom and that this would become a spark that would fire the workers' consciousness. That his prognosis was in large part correct was borne out by the sudden increase in strikes after the war. It must be pointed out, however, that the article showed no indication whatsoever of any critical view of the war, and this lack of criticism was a position shared by the overwhelming majority of the Japanese people at the time, it must be said.

The article 'Chinese Tailors' Strike in Shanghai' described a successful eight-day strike by 2,000 clothing workers who demanded and obtained higher wages and better food. The strike began in the second half of October 1895, at the time when the Machias had returned from its Yangtze patrol and was docked at Shanghai. The article was based on what Fusatarô had seen and heard himself, and on materials he had gathered; it was no mere account of the factual process of the strike but also a real analysis of it. He investigated the reasons why the strike was successful despite the workers' disadvantageous situation and pointed up the importance of the workers' sense of 'solidarity and brotherhood' which, it can be said, stemmed from their national character as Chinese. His analysis was not based only on what he experienced in Shnaghai and the materials he gathered there; it can also be surmised that his ideas were based on the various opportunities he had had of associating with Chinese people in America and of learning about their national character. Fusatarô certainly had some prejudice against Chinese, but he was clearly no mere xenophobe.

Working as a US Navy sailor while writing English language articles and compiling a dictionary at the same time - all of this has to be seen together to understand the man that Takano Fusatarô was at that time; it all belongs together. His sister and her husband Iyama Kentarô were of the view that Fusatarô's occupation as a sailor was 'wretched work', and Fusatarô himself certainly also felt that his status as a foreigner working for the US Navy was an embarrassment, but he did not share the Iyamas' view that it was 'a detestable hardship'.

It is noteworthy that Fusatarô himself did not regard his circumnavigation of the world on a gunboat simply as a trip to expand his own experiences, but he used his experiences in each country to think about the future of Japan and sought opportunities to share his observations with others. He had always been fond of the journalistic role of bringing new knowledge and information to others. Even when he had been so busy setting up the Japanese goods store in San Francisco, he had been sending 'reports' to the Yomiuri Shimbun. In later years, while active as a labor activist, he would bring together his experiences and observations in English language articles and essays and support himself by this means. Such work gave his life purpose and was a source of self-respect on which he could rely.

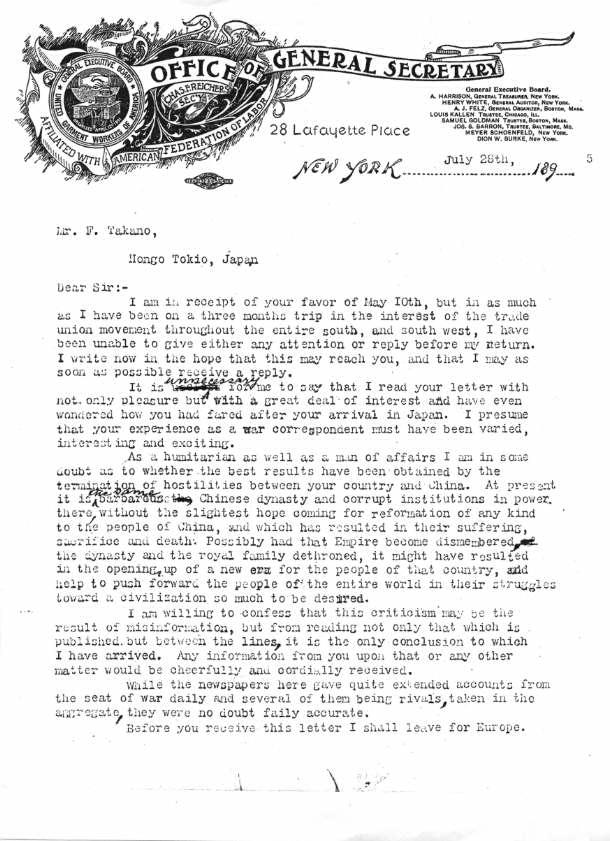

Fusatarô the would-be war correspondent

Let us take a look at a letter he received from Samuel Gompers during his period as a sailor. Gompers wrote it in reply to one he had received from Takano.

Mr.F.Takano,

Hongo,Tokio,Japan.

Dear Sir,

I am in receipt of your favor of May 10th, but in as much as I have been on a three months trip in the interest of the trade union movement throughout the entire south, and south west, I have been unable to give either any attention or reply before my return. I write now in the hope that this may reach you, and that I may as soon as possible receive a reply.

It is unnecessary for me to say that I read your letter with not only pleasure but with a great deal of interest and have even wondered how you had fared after your arrival in Japan. I presume that your experience as a war correspondent must have been varied, interesting,

and exciting.

As a humanitarian as well as a man of affairs I am in some doubt as to whether in the best results have been obtained by the termination of hostilities between your country and China. At present it is as some barbarous Chinese dynasty and corrupt institutions in power there, without the slightest hope coming for reformation of any kind to the people of China, and which has resulted in their suffering, sacrifice and death. Possibly had that Empire become dismembered, the dynasty and the royal family dethroned, it might have resulted in the opening up of a new era for the people of that country, and help to push forward the people of the entire world in their struggles toward a civilization so much to be desired.

I am willing to confess that this criticism may be the result of misinformation, but from reading not only conclusion to which is published, but between the lines, it is the only conclusion to which I have arrived. Any information from you upon that or any other matter would be cheerfully and cordially received.

While the newspapers here gave quite extended accounts from the seat of war daily and several of them being rivals, taken in the aggregate, they were no doubt fairly accurate.

Before you receive this letter I shall leave for Europe.

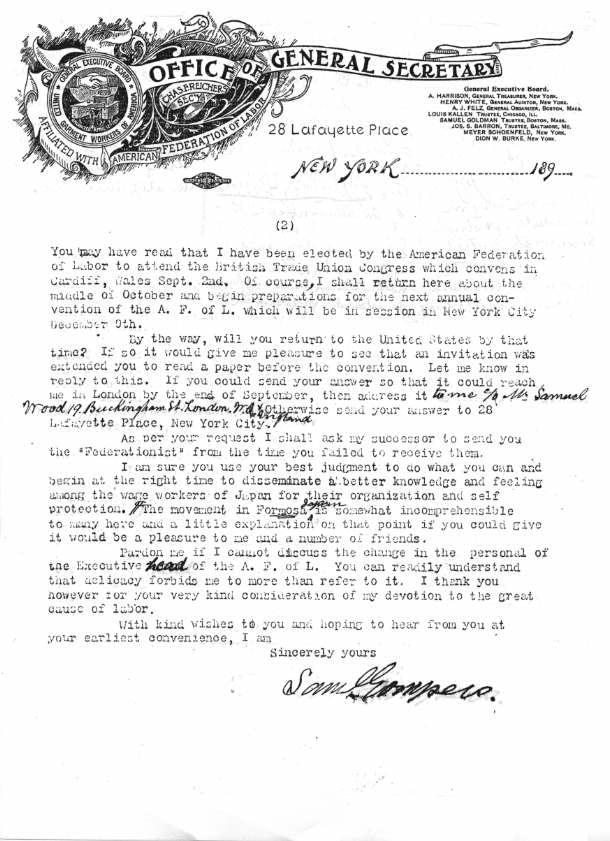

You may have read that I have been elected by the American Federation of Labor to attend the British Trade Union Congress which convene in Cardiff, Wales Sept. 2nd. Of course, I shall return here about the middle of October and begin preparation for the next annual convention of the A. F. of L. which will be in session in New York City December 9th.

By the way, will you return to the United States by that time? If so it would give me pleasure to see that an invitation was extended you to read a paper before the convention. Let me know in reply to this. If you could send your answer so that it could reach me in London by the end of September, then address it to me c/o Mr. Samuel Wood 19 Buckingham St. London. Otherwise send your answer to 28 Lafayette Place, New York City. As per your request I shall ask my successor to send you the "Federationist" from the time you failed to receive them.

I am sure you use your best judgment to do what you can and begin at the right time to disseminate a better knowledge and feeling among the wage workers of Japan for their organization and self protection. The movement in Formosa, Japan is somewhat incomprehensible to many here and a little explanation on that point if you could give it would be a pleasure to me and a number of friends.

Pardon me if I cannot discuss the change in the personal of the Executive head of the A. F. of L. You can readily understand that delicacy forbid me to more than refer to it. I thank you however for your very kind consideration of my devotion to the great cause of labor.

With kind wishes to you and hoping to hear from you at your earliest convenience, I am

Sincerely yours,

Samuel Gompers

This letter dated July 28th, 1895 was not written on AFL stationery but on that of the United Garment Workers of America. In fact, during that year Gompers was not the President of the AFL, though from the founding of the AFL in 1886 until his death in 1924 he was elected President 37 times in 38 years. 37 years is the longest period served by any president of any national center in the United States and is unparalleled in the history of the labor union movement worldwide. But 37 times in 38 years means of course that there was one year when he failed to be elected. That was at the Denver Convention in November 1894, shortly after his meeting with Fusatarô. He was defeated by John MacBride of the United Mine Workers of America, 1,170 votes to 976.

In accordance with the new executive committee's objectives, the AFL's head office was moved from New York to Indianapolis, right in the middle of the country. Gompers must have been allowed to use a room in the head office of the United Garment Workers of America. Half in jest, 1895 was said to be Gompers' 'sabbatical year', but of course, he continued to be in the frontline of labor activists. He journeyed far and wide during the year, from a speaking tour in the southern states and the Gulf of Mexico to a trip to Britain as the first US delegate to engage in discussions with the Trades Union Congress at their convention at Cardiff.

Most of Gompers' letter to Takano deals with his assessment of the Sino-Japanese War. In contrast to Fusatarô, for whom the war only had a positive side, Gompers considers what effects the war was having on the Chinese population and expresses doubt about Fusatarô's view. Gompers typed the letter himself and added corrections in pen. His respect and friendly feelings for Fusatarô are evident, and his high estimate of Takano Fusatarô is clear also from the fact that he invited him to attend the next AFL conference.

A noteworthy feature of the letter is that Gompers evidently was under the impression that Takano was a 'special war correspondent' for a newspaper. This must have been because Fusatarô had told him so. When he had left America he had told Gompers that he "had to return home suddenly on account of the war between Japan and China." As he had already arrived back in Japan, he must have written, contrary to the facts, that he had been to China as a 'war correspondent'. Once a lie has been told, it tends to be repeated. In his next letter, he wrote of "a stay of several weeks in China", giving the impression he had been there for just a short while. But in fact, when he wrote Chinese Tailors' Strike in Shanghai, he had been in China for nearly ten months.

It was his brother who saved him from getting caught up in such lies. All the letters from Gompers and Gunton were sent to his brother's Tokyo address at "180, Sendagi-Hayashi-chô, Hongo, Tokyo". In other words, Fusatarô sent all his letters to his brother Iwasaburô, who forwarded them to the US. Letters from the US arrived in Japan and were sent by Iwasaburô to the USS Machias c/o the US consulate in China. Iwasaburô graduated from his university's law department in July and in September began his postgraduate studies. Years later Iwasaburô recalled those days:

Thinking back to those distant events of over 50 years ago, in July 1892 I graduated from the No. 1 department of the then First High Middle School (today, the Humanities Department of the First High School) and straightaway began to study Politics at the Law Faculty of the Imperial University, from which I graduated in July 1895. At the time of my graduation, I was faced with a number of severe difficulties with regard to my future objectives. While I felt that on account of my personal circumstances, I had immediately to look for a position, on the other hand, I felt the great desire to do research work; I was driven by the urge to find a way to pursue a career within the academic world. Furthermore, my area of interest was labor issues and social problems. After I had given this some serious consideration, I finally made up my mind and took the risk of embarking on postgraduate studies and opted to major in industrial economics especially in labor issues under Prof. Kanai Noburu. [Tôkeigaku wo senkô suru made - My Life until my Specialist Studies in Statistics]

Fusatarô's influence is evident in his remark "...my area of interest was labor issues and social problems". Unable anymore to rely on remittances from his brother, in order to support himself, Iwasaburô had had to do part-time teaching at a middle school where he taught western and Japanese history and German and was frustrated at not being able to focus solely on research work.

Gompers' estimate of Takano

On Nov. 24, 1895 the USS Machias, which had been in dock at Shanghai undergoing refitting and resupply, left Shanghai and headed for Korea. On the 28th she arrived at Chemulpo, about 30 km west of the capital Seoul, through the center of which flows the Han River that reaches the sea at Chemulpo. It was a town well-known as the location of the signing of the Treaty of Chemulpo (1882), but today that name does not appear on maps of the region. Today Chemulpo is a part of the city of Incheon in Incheon Bay. At a time when seagoing transport was the main means of international trade, Chemulpo was then the lobby of the Korean capital. The Machias remained there for over four months, until April 1896. Fusatarô doubtless visited Seoul during this time.

Probably owing to his long stay there, Fusatarô was able to write a number of letters and reports to Gompers. One of them was the already cited "Chinese Tailors' Strike in Shanghai". Fusatarô apparently sent this with an accompanying letter, which has not survived, but we have Gompers' reply of Feb.18, 1896. Here is the full text:

Mr. Fusataro Takano,

180, Sendagi-Hayashi St., Hongo, Tokio, Japan.

Dear Sir:

I am in receipt of your favor of December 15 dated Chemelpo, Corea, and was exceedingly interested in reading both your letter and the article which you so kindly wrote for the AMERICAN FEDERATIONIST.

It is unnecessary for me to say that I read your letter with not only pleasure but with a great deal of interest and have even wondered how you had fared after your arrival in Japan. I presume that your experience as a war correspondent must have been varied, interesting, and exciting. You know that I am exceedingly interested in you and your observations and your correspondence has been of such a character as to make our acquaintance somewhat more than an ordinary friendship.

I hope now that the war is at an end, that you will obtain some remunerative employment and that you will be enable to utilize your talents for the purpose of helping to organize the wage workers that have accrued to the country and to the moneyed classes in the progress of the past 25 years.

By a strange coincidence you wrote your letter the day after I was re-elected to the presidency of the American Federation of Labor, and I am now located at Indianapolis, Indiana.

Having had the pleasure of issuing you your first commission as general organizer, it gives me more than ordinary gratification to renew your commission. You will find it herein. I also mail to your address copies of the Federationist from and including October, the February issue of which I edited. I also mail to you a copy of the proceedings of the New York convention for I know you will be interested in the work done there.

With kindest regards and hoping to hear from you soon and as frequently as you can make it convenient, I am.

Fraternally yours,

Samuel Gompers,

President, American Federation of Labor

As noted earlier, almost all Fusatarô's mail was sent to America via his brother in Tokyo, but an exception was his letter of Dec. 15, 1895, which was sent directly from Chemulpo. By chance, the following day, Gompers was re-elected President of the AFL at the 6th Convention of the AFL, where he defeated the incumbent MacBride by a slim margin: 1041 votes to 1023. Because of this good timing and his great interest in Fusatarô's report about the strikes in China, Gompers' letter was no mere social pleasantry, but an expression of his high regard for Fusatarô.

In his own letter, Fusatarô seems to have written that being a "war correspondent" was neither a stable occupation nor a good example of migrant labor. Gompers replied that I hope...that you will obtain some remunerative employment. Gompers seems to have sensed that there was something unnatural about Fusatarô's lifestyle following his 'return home' and even writes:

It is unnecessary for me to say that I read your letter with not only pleasure but with a great deal of interest and have even wondered how you had fared after your arrival in Japan. I presume that your experience as a war correspondent must have been varied, interesting, and exciting.

He had written exactly the same words in his previous letter.

In fact, before he received Gompers' letter, Fusatarô had already learned of his re-election as President of the AFL and sent a letter of congratulation on Feb. 5, 1896. As that letter gives a clear indication of Fusatarô's anti-socialist position, we shall quote it in full:

180, Sendagi-Hayashi St.,

Hongo, Tokio, Japan.

Feb. 5, 1896

Samuel Gompers Esq.,

N.Y. City, New York, USA

Dear Sir,

Let me first of all, congratulate you of your election to the presidency of the Federation. I believe that the cause of the American working people is best served by you, and I do heartily indorse the action of the late convention in rejecting every proposition of the socialists and electing one whose ability and good judgment cannot be well disputed. Crowning successes of the Federation and renowned honors in you are the earnest hopes of a friend in the Far East.

I found upon a brief investigation, a strong labor union existing in this city which, in its every aspect is a best type of union to be hoped for in the present condition of the Japanese workers. I refer to the Tokio Carpenters' Union. I shall, however, pursue my investigation little further and report to you at an early date.

I am intending to write an article to a Japanese magazine concerning the American labor movement with special regard to your Federation. 1 shall be very much obliged if you will favor me with one of your photographs which I will endeavor to publish with the article.

With best wishes, I remain

Yours truly,

Fusataro Takano

How could he have obtained this information about the Tokyo Carpenters' Union while in China and Korea? Most likely this was from his brother Iwasaburô, who was specializing in labor issues in his postgraduate research. It is noteworthy also that he was planning to write an article for a Japanese magazine about the American labor scene and especially about the AFL. Although he still had no secure prospects for his livelihood after his eventual return to Japan, it is clear that he saw his contribution in writing for newspapers and magazines. Gompers promptly sent a reply to Fusatarô's letter:

March. 7, 1896

Mr. Fusataro Takano,

180, Sendagi-Hayashi St.,

Hongo, Tokio, Japan.

Dear Sir:

Your favor of Feb. 5th came duly to hand and contents noted, and as usual am very much interested in hearing from you for I know you always have something worth reading to say. Certainly the result of your investigation showing the existence of a fairly strong Carpenters Union is of that character, and I shall make note of it in the next issue of the FEDERATIONIST.

I mail to your address with this two copies of the March issue containing your article on the Chinese Tailor's Strike.

If there is anything of an interesting character that may result from your future investigations I shall be pleased to have you do as you say--report it to me. You can see that I am interested in what you write since I published both your articles as you wrote them.

Permit me to express to you my sincere thanks and appreciation of your kind words of commendation of my efforts in the American Labor Movement and to thank you very much for your congratulations upon my election to the Presidency of the A. F. of L.

I believe with you and it is some gratification to find men with the courage of their convictions and who dare declare them even under adverse circumstances when it may detail inconvenience and discomfiture. In this instance, however, the trade unionists of America have applauded and ratified my position.

I mail to your address, with this, a few documents which we have just issued and which may be interesting to you, possibly aiding you in the writing of the article for the Japanese magazine on the American labor movement.

I haven't a good photograph here but enclose a picture of me which is fair and which you are at liberty to use.

With kindest regards and best wishes, and hoping to hear from you frequently, I am, Fraternally yours,

Samuel Gompers

President,

American Federation of Labor

On April 4, 1896 the Machias departed Chemulpo for Nagasaki, where she arrived two days later. Whereas on her previous visit she had stayed for just 48 hours, this time she remained in port for nearly two weeks, until April 18. After then returning to Shanghai and Zhifu, the Machias once again headed back to Japan on May 26; this time the destination was not Nagasaki but Kôbe and Yokohama. On arrival at Kobe at the end of May, she remained there for over two weeks.

Leaving Kôbe on June 17, the Machias steamed towards Yokohama, which she reached the following day. Exactly ten years earlier, at the end of 1886, Fusatarô had left Yokohama for San Francisco. In other words, it had taken him about ten years to travel around the world. When he had left Japan, he had been a youth, aged just 17; now he was a young man of 27. He had not been able to realize his dreams of success in the world of business, but he was now returning with a new dream: he would inform his compatriots of the positive role that was being played by the labor union movement in America and in other countries and he would contribute to improving the situation of workers in Japan. The USS Machias remained in Yokohama until August 1 before departing once more for Chemulpo. It was during the one and a half months that the Machias was docked at Yokohama, that Fusatarô jumped ship and effected his return home.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), Chapter 7 Amerika kaigun no suihei

|