8 A Call to All Workers

- To form trade unions -

Takano Fusatarô - translator and reporter

It is not known when exactly Fusatarô escaped from the USS Machias. Having decided to go back to Japan, it was only natural that he should desire to return home as soon as he possibly could, and he most likely jumped ship not long after the Machias arrived at Yokohama on June 18. He still had almost a year of his contract to run, so he had to forego $32.36 in pay, or 65 yen, the equivalent of half a year's wages for a craftsman in Japan. In order to prevent sailors from desertion, the US Navy was accustomed to pay the first month's salary only at the end of a sailor's period of service. Historical evidence for Fusatarô's return home is the following letter he wrote to Samuel Gompers:

143 Higashikata Machi

Komagome, Hongo,

Tokio, Japan, July 5, '96

Mr. Samuel Gompers,

President Ame. Federation of Labor,

Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S.A.

Dear Sir,--Your favors of the Feb. 18th and Mar. 7th have been duly received. The accompanying circulars and magazines, together with the renewed commission of the organizership, also came to hand, for which please accept my utmost thanks.

I enclose herewith an article for the Federationist. It is a rather long one, but points out one of the serious phases in the existing conditions, which, I believe, will be an interesting subject to you.

I cannot refrain from saying a word about the Federationist. Since your reinstallation to the editorship, it shows a great improvement, especially its editorial column. It is full of conservative yet sagacious suggestions. It presents ideas that are practical and feasible. Your argument against the cheap unions is particularly worthy of commendation. The American workers are to be congratulated in having such leader of high ability.

I have forwarded to you a month ago a copy of a magazine in English published by Japanese. I hope it has reached you safely.

I am still busily engaged in seeking a remunerative position. Accustomed as I was to the higher wages of the States, it is really a hard undertaking to find a work that will satisfy me. It often occurs to me that to return to the States again is better to my personal interest, but each time, thought of my life's object conquers to the selfish motive. I hope the time will soon come when I will finally settle down and spend my whole energy in the work of amelioration of the workers.

As you notice from the heading of this letter, I moved my abode. I shall be very much obliged if you will kindly send the magazines to the new address.

Yours respectfully,

F. Takano

This letter proves that at the latest, Fusatarô must have returned home by July 5. The most noteworthy point about the letter is that it states that "my life's object" is to "spend my whole energy in the work of amelioration of the workers." This will be an important source when we come later to consider the question of who led the reconstruction of the Friends of Labor and set about starting the workers' movement in Japan. He complains about the difficulties of finding suitable work, but these would soon be solved when he secured a post at an English language newspaper in Yokohama. This too we learn of from a letter to Gompers.

Office of the "Daily Advertiser,"

Yokohama, Japan,

Oct. 10, l896.

Mr. Samuel Gompers,

Dear Sir, --Your favor of the July 28th has been duly received. By the following mail, I have received a letter from Mr. Howard of the Spinners' Union, accompanied with several valuable pamphlets which furnished me with much of information I have been seeking.

I am now working in an English newspaper published in this city in a capacity of translator. As you will see from accompanying copies, it is a regular country paper, if you compare it with the publications in your country, but it goes in Yokohama and its circulation is the largest among the Yokohama papers. You will naturally ask "how many." Only six hundred copies and yet it is about a hundred ahead of all the other papers. I do not think I will remain in the office for a long time to come. Besides, the remuneration is small (though it is great deal better than the similar work in Japanese papers) I have so little time to spare that I could not do any other work, -- I have been even forced to put aside the investigation I have been pursuing on the condition of the Yokohama working people.

The strike, as you will notice in the accompanying papers, has become one of frequent occurrences in this country, which goes to show that working people are thoroughly dissatisfied. It is also to be noted that every strike so far inaugurated has been successful, nor is this very strange if we take into consideration the condition of market. Never before the demand for labor has been so intense as at present and it is not much out of reason to declare that Japanese workers have now a chance to bring the employers down to their knees without much effort if they are led by a leader of ability. For my own part, I regret my inability to offer them any assistance of material character. Whenever I saw a report of strike in a paper, I really long to be in the place where it is going on and advise them upon a plan of battle but I always restrain myself in view of expense I have to insure in doing so. Still I do not propose to remain idle for a long time and someday I shall be able to tell you of what I have done for the amelioration of the workers.

With best wish to you and your organization, I remain,

Yours faithfully,

F. Takano.

P.S. Kindly address me at my Tokyo home as before. F.T.

He writes that he is working "in a capacity of translator", but what he was most likely engaged in was selecting articles from Japanese newspapers and magazines and translating them into English. Such work made the most of his excellent English ability; it was suitably fulfilling work for him. Fusatarô states his dissatisfaction that he has little spare time and that the remuneration is poor. It is as though he could show his real feelings more directly when writing in English than in Japanese; grumbles and complaints are often to be found in his letters to Gompers.

The status of an English language newspaperman in Japan at that time was certainly not low. The distinguished novelist Natsume Soseki tried and failed to gain employment after his graduation working for the Japan Mail, an English-language newspaper based in Yokohama, and he ended up being appointed as a teacher at a middle school in Ehime Prefecture in Shikoku. To become a writer for an English language newspaper was a profession much to be desired by a graduate of the Imperial University.

The riddle of the rebuilding of the Friends of Labor

We shall turn now to the question of the process of the reconstruction of the Friends of Labor (Shokkô Giyûkai), which was the predecessor of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions (Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai). Previous scholarship has invariably drawn on Nihon no rôdô undô (The Labor Movement in Japan) by Katayama Sen and Nishikawa Mitsujirô, which states that

Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke reorganized the Friends of Labor in Tokyo in April 1897 and that Sawada traveled to Yokohama to persuade Takano to give his cooperation.

However, this account differs greatly from the actual events. Before his return to Japan, Fusatarô had resolved to organize labor unions in his homeland and had been recognized as the official AFL general organizer for Japan by Samuel Gompers. As preparation for this work, he had collected data on organizational forms of unions and on their cooperative activities, during his stay in New York. With regard to the matter of when to begin organizing in Japan, Fusatarô had not been persuaded by others; he had considered the timing himself and came to his own decisions. This is clear from the series of letters between him and Gompers such as that of July 5, 1896, already cited, and the following letter of Dec 11, 1896:

....The passing year was a most remarkable period in the history of Japanese labor movement. It was during the year that a great change has been noted of the public opinion in regard with the labor problem. There never was such a period as the passing year when the welfare of the working class was so much talked about. This remarkable progress of public opinion is attributable to the intense demand for labor as a result of the industrial advancement on the one hand and the repeated strikes on the other, as these factors are still existing, it will not be much out of the mark to predict that in the coming year we are going to witness actual efforts being made at every side for the interest of that much abused class of people in this country.

Here let me announce to you that I myself am going to try a hand in them. I had come to this decision a month ago but so circumstance I was at the time that I have hesitated. As the days passed on it became so apparent that a golden opportunity is at hand and to allow it to pass off with no effort being made on my part is a folly.

I have had no more time to hesitate and leaving the office of the Daily Advertiser a week ago I went up to Tokyo with a view of consulting a friend of mine, shoemaker by the profession. Result of the consultation was mapping up a plan of campaign which is to begin with an effort to present an address to the Lower House of the Diet, which will meet on Dec. 22nd and continue in session for three months, praying for enactment of a law regulating organization of working people by trade. I will advocate in the address that the law must dwell upon the chief points of trade unionism only, leaving management and governing of the unions entirely in the hands of the unions themselves.....

In November 1896 then, Fusatarô resolved to begin work on organizing a labor movement and in December quit his job at the Daily Advertiser.

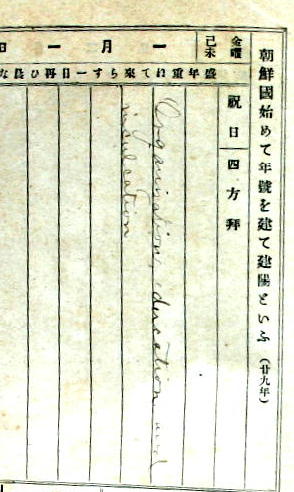

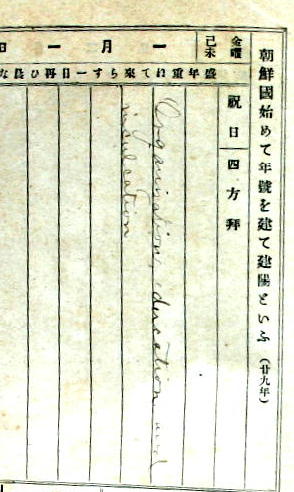

At the first page of his 'diary' for 1897, January 1st, he wrote four words in English "Organization, education and inculcation" - this was his New Year's resolution. Similar words expressing his determination as a labor activist are found on other pages of the diary.

Jan. 18 (Mon.)

Is it not necessary for those who seek to campaign on labor issues to have this attitude? All the more so because this is Japan's first labor movement. I must look around, understand how things are and make my move only after serious consideration.

Jan. 20 (Wed.)

If I behave like the kind of agitators who are currently active in society, it will destroy the movement. I must be faithful, persistent and prudent. To embark on the prospect ahead, which is as boundless as the ocean, calls for an extraordinary resolve.

On January 26, 1897, Fusatarô left Yokohama and moved to live in Tokyo. His new address was 143 Komagome-Higashikatamachi, Hongo, where his mother was running a boarding-house for students. Fusatarô must have felt that to start the movement, it would be better living in Tokyo, which had far larger industrial districts than Yokohama, besides his old comrades of the Friends of Labor were lived in the capital. In his diary for that day, he wrote: I left for the capital this morning at 10.30 a.m. together with Kawai. On the way we called on Jô and Sawada. Jô was Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada was Sawada Han'nosuke, his two comrades from the days of the Friends of Labor in San Francisco; they had returned to Japan about the same time as Fusatarô.

It is evident from this 'Takano diary' alone that the account of the reconstruction of the Friends of Labor that is based on the following passage in Nihon no rôdô undô by Katayama and Nishikawa is in error.

"In April 1897 Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke refounded the Friends of Labor in Tokyo. To gain the support of the journalist Takano Fusatarô, Sawada visited him in Yokohama and persuaded him to join them."

Such could not have been the case. When Sawada is supposed to have visited Takano in Yokohama, Fusatarô had already lived in Tokyo. Moreover, the reason why he had moved to Tokyo was to set in train the labor movement.

"Attended the Shakai-seisaku Gakkai; finally became a member"

On Feb. 7, 1897, some 10 days after his move to Tokyo, Fusatarô was taken by his brother Iwasaburô to attend a meeting of the Shakai-seisaku Gakkai (Social Policy Association). The association made a start in 1896 followed in the German academic society "Verein für Socialpolitik", among mostly young scholars graduated from the Faculty of Law of the Imperial University. It became a principal academic association in Japan for studying economics and sociology, and has a longest history as an academic society in the social science field, second only to the Kokka Gakkai (Political Science Association). But in its early days, it was no more than a small research group composed of young scholars of economics in Tokyo area.

The Takano diary recorded the occasion in a short sentence with deep emotion.

February 7th (Sun.)

This afternoon I went to the Gyokusen-tei in Kudanzaka-shita to attend a meeting of the Shakai-seisaku Gakkai and finally became a member.

The meeting place, Gyokusen-tei was a kind of rental space where it was possible to "have a discussion while enjoying tea and biscuits". That day, Fusatarô was not only attended a meeting but also he was admitted as a regular member of the Shakai-seisaku Gakkai. "Finally (tsuini) became a member" - this simple phrase expresses something of the complexity of his feelings. The happiness he must have felt would have been as one mere higher elementary school graduate could have discussed on an equal basis with other scholars of the Imperial University graduates.

"Finally (tsuini) " - this word conveys his long and ardent wish to join the Association. He had wanted becoming a member of the Shakai-seisaku Gakkai because he thought the cooperation of influential people was indispensable for trade unionism to be rooted in Japan. Five years earlier, he had already written a piece for the Kokumin Shimbun titled "Appeal to Prof. Kanai and Dr. Soeda" in which he had written: "I am greatly desirous that for the sake of the Japanese Empire, both of you would apply yourselves to the organization of laborers' unions". By joining the Association that was organized by pupils of Professor Kanai Noburu of the Imperial University, Fusatarô gained a forum that provided endless scope for discussion of labor issues with 'influential' researchers in the field.

However, he did not appear to get the amount of support he had anticipated from the members of the association, and in a letter written to Gompers soon after joining, complained that 'those who professed to be the friend [sic] of labor' had only a rudimentary knowledge of the labor movement and gave him neither cooperation nor sympathy. In the letter dated Feb. 20, 1897, he wrote:

I really need every encouragement from my friends across the water. Sympathy of my country for my effort I cannot expect nor co-operation for my work from those who professed to be the friend of labor. They spoke socialism, they talk necessity of a factory law, but none, absolutely none, of them understand potency of trade unions. For that matter they lack even primary lessons on the practical labor movement. Thus I have really hard work before me to educate working people to the necessity of union and these so-called friends. For the latter I have very little to do at present, suffice it to keep them from trying dark hands against us.

In fact, some members like Suzuki Jun'ichirô, Takano Iwasaburô, and Tajima Kinji did cooperate in Fusatarô's ventures, further Kuwata Kumazô and other members of the Social Policy Association were well-disposed towards him. Yet the dissatisfaction he felt was due to the too much expectations he had had that the members of the Association would be sure to help him.

Getting to know Sakuma Tei'ichi

However, just two weeks after sending that letter with its pessimistic outlook, at a certain study meeting, Fusatarô encountered a man who would become a powerful supporter. He made the acquaintance of Sakuma Tei'ichi, owner of the printing company, Shûeisha. Let us first cite a passage from Fusatarô's Diary that relates their initial meeting:

March 6 (Sat.)

Went to a meeting at the Imperial University Alumni Hall in the afternoon. Professor Kanai and Sakuma Tei'ichi were there. What Sakuma had to say about labor was very interesting.

It was at the same meeting that Fusatarô first met his brother's Professor, Kanai Noburu, with whom he had also earlier engaged in a debate in the Kokumin Shimbun. However, while Fusatarô in his diary merely noted the presence of Prof. Kanai, with regard to Sakuma Tei'ichi, he recorded positively that what Sakuma had to say about labor was very interesting. The diary goes on to note:

March 10 (Wed.)

Wrote to Sakuma Tei'ichi this evening proposing we meet on the 12th.

March 12 (Fri.)

Visited Sakuma Tei'ichi at 9 a.m. Conversation for over an hour. Left to visit Jô [Tsunetarô].

Just four days after meeting Sakuma for the first time, Fusatarô wrote to him to ask a meeting between the two of them. Wanting to meet two days later on the 12th suggests a rather direct and hasty request. Sakuma readily responded to Fusatarô's request and on the morning of the 12th the two met for a conversation of over an hour at Sakuma's home. In these two meetings, Fusatarô seems to have really taken to Sakuma, and two days later, this time without a prior appointment, visited the Sakuma's house late at night together with Tajima Kinji.

Sakuma Tei'ichi, the eldest son of Sakuma Jin'emon was born in June 1848 in Shitaya Minami-Inarichô, Edo [Tokyo]. He was 20 years older than Fusatarô. Originally from a farming family, his father had become a 'niwaka samurai' (sudden samurai) by purchasing a privilege of lower rank of samurai. At the very time Tei'ichi succeeded his father, the Tokugawa Shogunate ended. Although, as a low- ranking samurai, he had never even seen the Shogun, Sakuma joined the Shôgitai; army of the shogunate and fought against the forces of the Satsuma and Chôshu clans in the Boshin Civil War. With the Meiji Restoration, he followed Tokugawa Iesato to relocate in Shizuoka and a son of a 'sudden samurai' ended up becoming a last vassal of the Tokugawas.

Although he did not make his mark as a samurai, after moving into the business world, his independent spirit and foresight secured him one success after another. After leading the people of Amakusa Islands (well-known for their diving skills) in the development of Hokkaidô, he succeeded in raising a French ship that had sunk in Izu bay; he was a rare breed of 'entrepreneur'. In October 1876 he made a successful move into the printing business. That was Shûeisha, the forerunner of today's Dai Nippon Publishing Co. Ltd. He went on to found Dai Nippon Toshôgaisha (Japan Publishing Company) and Tôkyô Itagami kaisha (Tokyo Paper Board Company), both of which ventures also saw success.

In 1889 he was elected as a representative in the Tokyo City Assembly and re-elected four times thereafter. He founded the Printing Trade Association, the Tokyo Lithographic Trade Association and served as the chairman of both associations. He was a member of the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce and appointed the head of the Chamber's manufacturing section. He was also selected as a member of the High Commission of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce and played an active role as a leader of the business world in Tokyo.

Sakuma Tei'ichi was certainly a man in the capitalist camp, but he understood the significance of trade unions and in 1892 he published an article titled "The Necessity for Factory Workers' Unions". In this paper he criticized the idea that reductions in workers' wages meant higher profits for capital and argued that the role of the worker as producer and consumer was an important element sustaining the economy as a whole. This argument completely matched the view that Fusatarô had held for a long time. As Sakuma argued for factory workers' unions = trade unions as a means to prevent reductions in workers' wages through layoffs, he came to be known as 'Japan's Robert Owen'.

Japan's first lecture meeting on labor issues

Takano Fusatarô was not only taken by Sakuma Tei'ichi; the businessman also seems to have been much impressed by Takano's knowledge and intelligence. Ten days after their second meeting, Sakuma wrote Takano a letter inviting him to give a lecture to the annual meeting of the Tokyo Industrialists Association.

Takano's diary records the following:

March 22 (Mon.)

This evening an invitation came from Mr. Sakuma Tei'ichi for me to give a lecture to the Tokyo Industrialists Association meeting on April 6. I immediately replied, accepting the invitation.

The Tokyo Industrialists Association was an organization that brought together unions of the owners and managers of various factories and workshops. It had been founded in 1891 through the advocacy of Sakuma himself, then head of the manufacturing section of the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce. Although it was supposed to be concerned with manufacturing, of the total of 26 unions involved, 11 - almost half - were craft business unions in the building trade: carpentry, plastering, stone masonry and so on. The rest were cast metal businesses, foundry businesses, vehicle makers, printing and publishing businesses. This was a meeting of the upper ranks of those industries, so those attending the general meeting would mostly have been owners or those in senior management positions. However, though they were management people, as mostly small manufacturers, they were all engaged in labor themselves and knew the actual conditions of their workers.

Fusatarô's Diary contain the following entry on the meeting:

April 6 (Tues.)

1 pm Attended the Tokyo Industrialists Association's General Meeting at Kinikikan. Takeuchi Tsunetarô spoke about thrift and saving, and I spoke on the power of workers in America.

A problem here is that in a letter to Gompers, Fusatarô described this meeting as "the first public meeting ever held in this country with the sole object of advocating the cause of labor" and claimed that it had been "held under the auspice [sic] of the Friends of Labor":

I have, at last, the honor to inform you that the first public meeting ever held in this country with the sole object of advocating the cause of labor was held under the auspice of "the Friends of Labor" on the 6th inst. at the Kinikikan, Kanda, this city, when several hundred workman attended despite a pouring rain and addressed by Messrs. T. Sakuma, owner of a large printing establishment in this city and a hearty sympathizer to the cause of labor, K. Tajima, a graduate of the Imperial University, T. Takeuchi, a student of social problem and myself......

I myself advanced the organization of workers as the best means to promote the interest of workers, dwelling at a great length upon the method of formation of the trades unions, explaining the plan of American trade unions and the A.F. of L. It can not be said that the meeting has done much toward the labor movement in this country but it serves as a foundation of future work.

(Takano Fusataro's letter addressed to Samuel Gompers dated April 15th, 1897)

Needless to say, the record given in the Diary is closer to the truth of the matter. In his letter to Gompers, Takano seems to have wanted to report some early results for the movement and so told the lie that the meeting was held under the auspices of the Friends of Labor. The contents of his lecture certainly amounted to promotion of the labor movement, so to describe the meeting as "the first public meeting ever held in Japan to advocate the labor movement" could perhaps be allowed as not too far off the mark. But to disguise the real holders of the meeting was simply improper.

Nevertheless, on that day, April 6 1897, the first page in the history of the Japanese labor movement was written, and at the meeting the Friends of Labor distributed the first Japanese booklet calling on workers to form labor unions in Japan. The letter to Gompers goes on:

At the meeting a pamphlet written by me, was distributed in which the benefit of organized action, the plan of formation, and the beneficiary system in vogue in the United States were fully set forth. I have enclosed a copy of it since it is the first of its kind published in this country. In the copy where it is marked "A" is the point where the plan of your federation and affiliated bodies was disclosed, the mark "B" denote where the great sum of money distributed by the Cigar-makers Int. Union during 15 years ended 1894 and the mark "C" of the plan of beneficiary system were set forth.

This pamphlet was the famous Shokkô Shokun ni Yosu: "A Call to All Workers". He clearly writes "a pamphlet written by me", and the places A, B, C which he marked out for Gompers were all passages based on things he had researched himself while in New York, a fact which alone is enough to establish the pamphlet as the work of Takano Fusatarô. Moreover, his diary for April 16 records that "this afternoon, gave notice of publication of Shokkô Shokun ni Yosu to the Ministry for Home Affairs". This too supports the fact of Fusatarô having been the principal behind the publication of the pamphlet. It must be acknowledged that the account in Nihon no Rôdô Undô (The Labor Movement in Japan) by Katayama and Nishikawa got important facts wrong when it gave the impression that Shokkô Shokun ni Yosu was written and distributed by Jô Tsunetarô and Sawada Han'nosuke.

"Call to All Workers"

Unfortunately, no extant original copy of this important milestone publication in the history of the Japanese labor movement, Shokkô Shokun ni Yosu (Call to All Workers), has yet been found, so the precise details as to what kind of pamphlet it was remain unknown. The content, however, is known, because the full text is included in Nihon no Rôdô Undô by Katayama and Nishikawa. As it was unusually long for a propaganda article, only the gist of it will be presented here, but it was the most important text Fusatarô wrote in his life, so I would like to present an overall picture of it. It begins as follows:

In the coming year 1899, the whole of Japan will be opened up to foreigners. Foreign capitalists will be looking to come into the country make use of low-paid, intelligent Japanese workers in order to make huge profits. Within three years, these foreign capitalists, with their different character and customs and with their long-established habit of treating workers harshly, will be your employers.

This was the so-called naichi zakkyo mondai (internal foreign residence issue). The areas to which foreign residence had been restricted, such as Yokohama and Tsukiji in Tokyo, were liberalized. In exchange for the abolition of extraterritorial rights, all restrictions on foreigners' rights to live, travel and do business anywhere were removed. Foreign capitalists were free to do business anywhere in the country. Many imagined that cheap Chinese labor would flood into the country and saw danger in their becoming competitors for Japanese workers.

The second theme of the pamphlet was the instability of workers' livelihoods. It was pointed out that accidents at work, illness and old age meant that if workers could not work, they would quickly run into difficulties and if they died, their families would soon fall into poverty; further, that factory mechanization increased the destruction of families' livelihoods and that wives and small children were now having to do factory work. With such arguments, the pamphlet sought to rouse male workers.

It is the height of unnaturalness for wives, who should naturally be defending the home, and for children, who should of course be attending school, to work in factories. The reason for this is that wages are too low, and when one learns that a worker cannot support his wife and children on his wage, it has to be said that this is extremely disappointing. Husbands feel strongly that their wives' lives should not be too hard and parents feel strongly that their children should not end up without an education.

This shows that Fusatarô's views of the family and of women were absolutely typical of a man of the Meiji period (1868-1912). As 'master of the household', a man had the duty to provide for his wife and children, while the wife's role was to protect the home. In seeking to organize workers, the Friends of Labor had in mind only the male workers. The pamphlet's closing section includes a clear call to them:

Stand up workers! Stand up and form unions, and in doing so, discharge your weighty duties and defend your self-respect as MEN.

This could hardly be expected to draw no criticism from feminists. But at that time, the labor movement in every country was a male workers' movement. And if there had then been an appeal to Japanese female workers to join unions, what would have been the likely response? The overwhelming majority of female workers in the silk reeling and cotton spinning industries were young girls who only worked in factories for the period before marriage. The objective of organizing unions and 'ignoring women' in doing so was inevitable given the limitations of the period.

The Call to All Workers goes on to appeal to workers not to get involved in improper and immoral behavior:

A further point that has to be mentioned here is your behavior. You are selling your labor power and maintaining your livelihoods by walking a righteous path, so as long as you take care to do no wrong, you will have no regrets and need fear no-one. However, once you do something improper or commit an immoral act, you will lose your right to be considered an upright person walking the path of righteousness and eventually you will destroy your body....if those in a disadvantageous position like yourselves want to amend their disadvantage but do not restrain their behavior, it will be hard for them to achieve any good results

"To raise workers' social status, workers must strive to cultivate themselves and must gain the trust of society" was an appeal often repeated in the Japanese labor movement in later years.

Finally then, a policy for the workers had now been enunciated, but the Call also included a statement of the political position of the Friends of Labor, which made clear their opposition to "revolution" in a well-known passage that is always referred to by commentators on the Call to All Workers.

You will no doubt be wondering: "what can we do?" Some assert the following: "The situation of society today is extreme in the literal sense of the word - the rich are getting richer, and the poor are getting poorer. The way that workers have been unjustly treated and have fallen into such a deplorable state is so terrible it makes one sad and angry. The only way to address this situation is by a revolution that equalizes rich and poor." This is a most trenchant argument, and if, as its proponents argue, society could be improved by such a revolution, that would be a fine thing, but the world is not the simple place those proponents take it to be. Under conditions of major disturbances, all kinds of unintended consequences can occur, and one frequently sees it happen that the objectives aimed for in the initial stages are not achieved....We therefore do not hesitate in giving you the following warning: turn firmly against revolution and strenuously reject all radical behavior. Leave to the egalitarian party foolish notions about demanding a mile when you cannot even gain an inch.

After the long prologue, the text finally moves to the main subject of trade unions, which forms the bulk of the Call to All Workers.

What we recommend to you is that people in the same industries combine to form labor unions with people with whom they get along so as to be able to aid each other on the basis of natural human feelings and that these unions collaborate over the whole country to effect nationwide cooperation....The reason why you have fallen into today's miserable situation has often because you have not been able to act in a united fashion. It is all too evident that today, given the imminent attack by foreign enemies and the significant obstacles within the country, those working in the same industries need to cease their strife against each other and act together in a united manner. If you do not combine and ride the great wave of social progress, if you do not cultivate healthy values within and firm action without, opposing foreigners and heartless employers and correcting abuses, then society will not move in the direction you wish. Rather, is it not the case that 'labor is sacred, union is strength'? Given a great enough load, even of feathers, you can sink a ship, so if those engaged in sacred labor unite in strength, when your energies gush forth, there is nothing you will be unable to achieve.

Here, in the opening period of the Japanese labor movement appeared the key phrase that so appealed to the hearts of Japanese workers: 'labor is sacred, union is strength'. Fusatarô had the phrase printed on the back of his name card. We shall leave the reasons for the importance of the phrase until later and for now, press on with the text of the Call. Fusatarô now proceeded to call for the formation of labor unions.

In America 150,000 railroad workers once managed to stop all traffic for three weeks on lines belonging to 24 railroad companies capitalized at $800,000,000. 30,000 English freight workers deprived the London market of food for three months. Although these were short periods, the actions did not achieve their goals, and while they could not take up violent action as with a revolutionary party, they made solid progress and showed a strength that was capable of defending what they had gained. Slowly, firmly, in calmness, peace and good order, those aims were achieved. These are the means you should adopt. We renew our call to you to form labor unions. How can such unions be organized?

1. Where there are seven or more workers in the same trade in a district or town, they can get together and form a local union.

2. The various unions in a district or town can combine to form regional labor federations.

3. The regional labor union organizations for a particular trade can then federate to form a national federated labor union body.

4. The national labor federations can then combine to create a national labor federation throughout the Empire of Greater Japan.

It was then explained how it was important for the solution of labor problems that occupational unions be set up in the various regions and federated nationally to form a united organization, and it was explained how trades such as carpenters, printworkers, and leatherworkers could be combined in areas such as Tokyo, Osaka and Nagasaki.

The text then moved on to labor unions' mutual aid provisions. Actual examples of the American cigarmakers' union's aid sums were given and their significance explained as follows:

When workers are afflicted by a calamity, they have no recourse but to turn to others for aid and as individuals, are often forced to lose face in doing so. Sometimes there is no-one to turn to, and they fall into greatly straitened circumstances. Mutual aid from the labor union, by contrast, is not 'charity'; it is a sum a man receives that is guaranteed him by what he has paid in, and no independent individual need therefore lose face in receiving it. Also, when one meets a misfortune, the means to deal with it have already been put in place so there is no need to resort to servile actions in order to cope with it. Therefore, the spirit of self-help and of self-respect and independence are promoted, which will be able to effect a great improvement in workers' social standing.

This links onto the next and final passage. Here it is helpful to be able to feel something of the mood of the original text, so it has not been rendered into modern style:

Stand up, workingmen! Stand up and organize unions, and in doing so, perform your great duty and preserve your honor as men. Your prospects are infinite. All you require is a steadfast spirit and an indomitable will. It is said that heaven helps those who help themselves. Rouse yourselves, workingmen! Show your spirit of self-reliance!

Finally, the one thing I want to say is that there may be some among you who feel that it is impossible to set up unions or that there are no precedents for doing so, nevertheless, if you do not set to it, when is a union going to be established? If you hold back in the face of the great enemy, will you not fall increasingly into foolish extremities on account of various personal circumstances and conflicts? Some of you may be apprehensive that there are few union members in this country, but even if, in terms of numbers, there are many men yet they do not awaken to their responsibilities really seriously and fail to join together, then as the saying goes, they will be just a crowd of birds on a hill and nothing will be achieved. Rather, if even a few men keep in mind their lack of status and strive hard for their own sake and for the sake of their wives and children, if, so to speak, the flower of workingmen, what we should call the death-defying band on the battlefield, join together, the movement they create will be a glorious one. Therefore, I am not concerned about numbers but rather that there are those with a will to step forward and a desire to enter upon this glorious battlefield. By nature, workingmen are rich in heroism. I am quietly confident that there are not a few among you who recognize yourselves as members of such a death defying band.

This Call to All Workers was written in long sentences in a classical style that was not suited for a declaration to workingmen but was rather aimed at explaining labor unions to a readership of intellectuals. It is doubtful that those workers who got hold of a copy of the pamphlet would even have been able to get through it or understand much of it. And yet, besides the production of this text, the only achievement of the Friends of Labor was to hold a single lecture meeting. Nevertheless, within just three months of the publication of the Call to All Workers, the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions (Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai) had been set up and itself, only six months later, gave birth to the Ironworkers' Union. We ought to recognize that the Call to All Workers had a far greater effect than we are accustomed to think. Furthermore, this fact shows that the intellectual level of workers at that time, at least at its highest level, was indeed considerable.

Takano Fusatarô's daily life as reflected in his diary

Thus far, we have followed Fusatarô's life mainly through his actions in society, but if one wants to gain a clear picture of an individual's life, one also wishes to know something of the private life. Unfortunately, that is by no means easy as often, little such information remains about an individual's daily life. If Fusatarô's family and intimate acquaintances had left a record of his private life, that would have been a useful source, but the information shared by Iwasaburô does not at all touch upon his brother's private life. Fortunately, however, one volume of Fusatarô's own diary does survive. In Meiji sanjûnen tôyô nikki (Diary for 1897), besides the daily entries, there are also sections recording visits to and from other people and cashbook section as well as an address book which gives the names and addresses of friends and acquaintances. But many daily entries are missing, what entries there are mostly of a simple memo type and do not give much in the way of personal or emotional information. Nevertheless, as a diary and an account book combined, it does reveal information unavailable from other sources.

For example, in that year 1897, Fusatarô relocated twice. Until late in January he was lodging with the Shimokawabe family in Tobechô, Kuraki County, Kanagawa Prefecture. The outgoings column of his diary shows that he paid five yen for his lodgings. Later, on those occasions when he went to Yokohama, he would often stay with this Shimokawabe family. In Yokohama were the two flourishing inns Takanoya and Itoya, run by his cousins, but there is no trace of him staying there. Lingering difficulties over the debts incurred in connection with his Japanese goods store in San Francisco would seem to have distanced him from these relatives.

On January 26 he went up to Tokyo, but after that there is no reference to 'rent' and 'lodgings money' in his diary, and it can be surmised that he stayed with his mother. He stayed for just a short time at 143 Komagome Higashi-katamachi, Hongo Ward and on May 8 relocated to 31 Oiwakechô, Hongo Ward. Masu moved quite frequently, but always in the area around the Imperial University, not only because of Iwasaburô's studies at the university but because it was convenient to run a students' boarding house there, where she could adapt to the levels of rents and the number of student lodgers.

One interesting point mentioned in the diary is that Fusatarô took up the practice of jûjutsu (judo). The references to it are as follows:

March 15 (Mon.)

Studied jûjutsu under Yagihara sensei

March 17 (Wed.)

Felt the effects of doing jûjutsu this evening; my body painful all over.

April 3 (Sat.)

....Went to Kôzandô in Nihonbashi to pick up the book on Jûjutsu requested by Mr. Sengoku, returned home, posted the book to him.

April 13 (Tues.)

In bouts with Mr Mori last night and tonight in one hold, I felt great pain in a bone on my left side. The teacher attended to me.

May 19 (Wed.)

Started jûjutsu again this evening.

June 23 (Wed.)

Started jûjutsu again this evening and injured myself again.

July 20 (Tues.)

Started jûjutsu again this evening.

Fusatarô does not write the reason why he thought of taking up judo. I thought perhaps that it was for self-defense in anticipation of violence encountered in the course of his labor activism, but from the interruptions and frequent restarts, it appears he was not such an enthusiastic student. The Mr. Sengoku mentioned in the April 3 entry had worked at the New York branch of the Yokohama Specie Bank and was an old acquaintance from Fusatarô's San Francisco days. Japanese abroad in those days were often asked about 'jûjutsu' and must have requested books explaining it to be sent from home. Fusatarô had a similar experience and as a result, may have thought he would take up the practice of judo one day. In passing, it can be mentioned that his monthly lessons cost 20 sen.

He was practicing judo in this year, so he must have been in good health on the whole. However, he seems to have suffered from toothache and on January 22 bought some 'toothache medicine'. He was also troubled by stomach pains and boils although only for short periods, as is clear from the following entries:

August 4 (Wed.)

Went to Sawada's at 4 p.m. returned home 8 p.m. Tonight much stomach pain, couldn't sleep.

August 15 (Sun.)

11 a.m. Went to Sawada's. Later, went to Mita Unitarian Church for a public meeting. Returned home 7 p.m. The stomach pains that came on yesterday have not stopped.

December 9 (Thurs.)

Treated by doctor for a boil on lower back

Noteworthy here is the reference to "visiting Sawada's". Such entries appear frequently from the end of June onwards. "Visited Jô" had been a frequent entry before that but references to him stop on June 21, and thereafter, appear the entries "went to (Mr.) Sawada's". This is because the office of the Friends of Labor moved from Jô's house to Sawada's shop. Fusatarô was the principal activist for the Friends of Labor (Shokkô giyûkai) and for the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions (Rodo-kumiai Kiseikai) so he was at the office almost every day. From late August the office of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions (hereafter Kiseikai) moved again, from Sawada's shop to a rented room at the Yanagiya. Fusatarô was at work seven days a week! But he was at the office mostly in the afternoon only; in the morning, he would be at home writing reports in English or doing translation work. That he always used rickshaws when he went out and also when he went to the office is evident from the frequent entry kuruma-dai (rickshaw charge) in the expenses column of his diary. Rickshaws were the contemporary equivalent of today's taxis, and although there was a horse-drawn railway stop only a short walk away, it seems he did not often use it. In passing, it can be noted that Katayama Sen's lifestyle was known for its frugality. Kôtoku Shûsui said: "I never see you riding a rickshaw". This was another difference between Takano and Katayama. Still on the subject of transport, Fusatarô also used to ride a bicycle, which was still unusual in Japan at that time. But this comes from a little later, when he is shown with a bicycle at the head office of the Ironworkers' Union at Hongokuchô. As can be surmised from the rickshaw charges, an important part of the diary was the 'incomings and outgoings' columns. From here one can gain the kind of insight into Fusatarô's daily lifestyle that cannot be obtained elsewhere.

Conspicuous is the amount of money he spent on tobacco. Amounts of 3 and 4 sen frequently recur, indicating that he must have been quite a heavy smoker. Money for refreshments such as cakes and rice crackers (senbei) also often recurs, but the amounts - from 10 to 20 sen - would suggest the purchases were for tea and cakes with guests and not just for himself. This bears out the memoirs of friends and acquaintances who remember him as being a sociable person. Another example of his sociability is this notable entry for February 14, soon after his relocation from Yokohama to Tokyo:

February 14 (Sun.)

Went to Ueno this morning at 11. Met Mitsubori, Kawai, Ikai, Tsunoda, waited for Iwasaburô to arrive then we all went to Shunyôrô [restaurant] for lunch. After that, we took a horse-drawn tram to Asakusa and had our photographs taken in the park then went for a walk to Kameido and saw ......... On the way back, we crossed the Sumida River by boat and arrived at Ryôgoku Bridge from where we walked to Kobikicho Manyasu, where I had a bath and then had supper.

For his expenses that day, Fusatarô recorded '5 yen 4 sen for western-style lunch, Manyasu 5 yen 43 sen' so it is clear that he paid for everyone. Those with him that day - Mitsubori, Kawai, Ikai, and Tsunoda - were all friends from his Kôgakukai days in Yokohama. On this day he must have repaid those who had given a farewell party for him in Yokohama by inviting them to a day out with him in Ueno and Asakusa. On November 3, he attended a 'Social Gathering for Those Returned from America'. The others present at the gathering at the Manyasu restaurant in Kobikicho were Kato, Sawada, Komatsu, Nakamura, Takekawa, Takezawa, and Okuda. In this period Fusatarô did not fail to attend regular meetings of the Social Policy Association, from which it can be surmised that he considered it an important group of people.

Fusatarô had no regular occupation at this time, but although he did not have much money, it seemed to pass through his hands easily enough. He entertained friends, used a rickshaw, and spent money on high priced items such as coffee and milk (61 sen) and biscuits (20 sen) which ordinary people would not have tasted. His purchases included a cigar for 25 sen.

All of these were 'imported goods'. They were only trifling luxuries that reminded him of his life in America. When he had more money, he would indulge himself more conspicuously. With his friends Ôsawa Ryûkichi and Suzuki Jun'ichiro, he certainly frequented the red light district. For example, the 'busiest' such period shown in the diary was the first week in April 1897:

April 1 (Thurs.)

Ôsawa came at 6.30 p.m. Went together to Nakakin for a drink. Afterwards, took a rickshaw to Senju. Went to a house [brothel] called Sekairô and spent the night there.

April 2 (Fri.)

Came back with Ôsawa, breakfasted at an eatery, parted and came home.

April 4 (Sun.)

Suzuki came this afternoon. Went together to Shioda Makoto's place and from about 5 p.m. went to Shinbashi to enjoy moon viewing. Then we went to Sagamiya in Nihonbashi. Came home at midnight.

April 5 (Mon.)

11 a.m. Went to the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce to get paid for translation work, strolled about here and there, met Suzuki at 5 p.m. and went to Kikuya in Nihonbashi for a meal and then to Sagamiya. Returned home at midnight.

April 6 (Tues.)

At 1 p.m. went to Kinkikan to attend a meeting of the Tokyo Industrialists Association. Takeuchi Tsunetarô spoke about thrift and saving, and I spoke about workers' power in America. Tajima Kinji argued for industrial unions.

At 5 p.m. participants had a meal. Left the Hall at 7, and called on Ôsawa. He wasn't at home so I went to n.q.

Nothing is known about this Ôsawa other than that he lived in Yamabushichô in Shitaya Ward. The income and expenditure column for April 5 shows that the translation fee Fusatarô received from the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce was 18 yen and 45 sen, and he spent 11 yen at Kikuya and at Sagamiya. This was to repay Suzuki for getting him the translation job, but his extravagant spending is noteworthy.

Also noteworthy are the events of April 6. This is his record of the evening of that 'Day One' in the history of the Japanese labor movement, when the Call to All Workers was first distributed. The 'n.q.' probably means 'northern quarter' and refers to the 'entertainment district' Yoshiwara, which was in the north of the city, which he concealed by rendering 'north' into English.

Fusatarô's easy ways with money may have reflected his long years of living alone and his habit of having only to look after himself and do what he wished.

At the same time, his background as a native of Nagasaki, known for the pleasure-loving, fashionable lifestyle fostered by its citizens, may also have played a large part.

Katayama Sen's lifestyle differed widely from that of Takano Fusatarô and provided another contrast between the two men. Katayama did not care about his physical appearance nor about his food. Yoshikawa Morikuni, who joined the editorial staff of the Katayama faction's journal Shakai Shinbun (The Social Gazette) after the Russo-Japanese War and was often in and out of the Kingsley Hall recalled that:

To add a word about Katayama, this writer has never seen him wearing western clothes. He would always be wearing his shorter length navy blue kimono with its flecks of white, and low clogs, carrying his flyers, a tin can with sumi ink, and a brush pen, leaving his house in the morning with his sour face and returning late at night. Without speaking, he would pour tap water into his bowl of barley [transl. this showed his frugality] eaten only with miso bean paste and pickled radish (takuan).

Next, let us look at Fusatarô's income and expenditure at this time. From the relevant columns of his diary, it can be seen that the largest amount of income came from the English language reports and essays he sent to America. For reports and essays submitted to American Federationist, Firemen's Magazine, The Gunton's Magazine he was paid 107 yen 44 sen. Next came money from the publishers Ôkura for his Japanese-English Dictionary (Wa-Ei Jiten) and English-Japanese Business Conversation (Ei-Wa Shôgyô Kaiwa) and for proof-reading done in connection with those publications. It is likely that he was also paid for the manuscript of Japanese-English Dictionary the previous year, but in 1897 he was paid 25 yen for it in March, 50 yen in June for English-Japanese Business Conversation and 15 yen in October for proof-reading - a total of 90 yen for the year. Additional money came for translations done for the Show-rooms of Exported Goods run by the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce - all that is recorded is 18 yen 45 sen on April 5. From the translations itemized, it would seem that some income entries may be missing. At the end of the year, he also received 15 yen for two weeks' work teaching English at Tokiwa Eigo Kôshûkai (Tokiwa English School).

Moreover, it is unclear whether this was income or loans, but the following income items are also recorded: Jan. 8 - '10 yen from Tokyo'; Jan. 23 - '30 yen from Iwasaburô'; Feb. 11 - '15 yen from Naniwachô'. The '10 yen from Tokyo' seems to have been a loan from his mother. Most likely, he had deposited with his mother the remainder of the debts he had repaid from his work in the US Navy. His board, food and lodging had of course been free during his service with the navy, and he had been paid a minimum of $32 a month. From May 1894 until June 1896 he had been paid a total of at least $800. It is unclear how much Fusatarô's personal debts and his mother's debts amounted to at the time he returned to Japan, but even if they had all been paid off, he would still have had some money in hand.

In total then, his income amounted to 285 yen 89 sen, an average of 23 yen 82 sen a month. This was not such a large amount, but he was living with his mother and was still single, so it was enough for an ordinary livelihood. Yet as his income was unstable and his ways with money were extravagant, he seems to have often been short of money. This is shown, for example, by the entry 'from the Society', which denotes a loan he obtained from the Kiseikai. The amount of such loans was 5 yen, but from September the number of 'from the Society' entires rapidly increases, reaching 19 times for the whole year. I had thought that these loans could perhaps have been allowances from Kiseikai but on December 3, when he received from America more than 35 yen for one of his English language reports, there is an entry in the diary which indicates that 30 yen was 'repaid to the Society', so clearly, this was a loan, not an allowance.

His support for the Yokohama ship carpenters' strike

Although Fusatarô was able to call for the formation of labor unions through the distribution of the Call to All Workers in April 1897, he did not immediately turn to the next phase of labor union activism. His diary shows that for the next two months he was engaged in the study of judo, and was enjoying the nightlife with friends, and for a labor activist, he seems to have been leading a rather relaxed life at that time. I wondered whether it might have been that he was disappointed that the Call to All Workers had found no response among the workers but my investigations showed otherwise. I came across evidence, albeit fragmentary, of workers' responses to the Call to All Workers.

For example, on May 2 Fusatarô's diary entry states: This morning Koide Kichinosuke called.

Koide would soon become an official of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions (Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai). He was a proof-reader of western texts at Shûeisha company. That Koide, who later joined the printworkers' unions Kôshinkai and Ôyûkai, should visit Fusatarô at this time was surely as a result of his having responded to the Call to All Workers.

Also deserving of attention is the relationship between the Yokohama ship carpenters' union and the Friends of Labor. In fact, a month before the foundation of the Kiseikai, some 400 ship carpenters had formed a union in Yokohama and the two surrounding districts and went on strike for higher wages. Fusatarô reported on the strike for American Federationist in an article entitled "A Remarkable Strike in Japan". In a letter to Gompers of July 3, 1897, Fusatarô described the strikers' leadership and their support:

I have been consulting with leaders or striking Ship's carpenters of Yokohama. They have formed a union with the purpose to strike, though they deny it, some four weeks ago. The strike is still pending and it is carried on Peacefully and orderly with prospect of final victory. I am endeavoring to bring the union to a firm basis and strongly advising its leaders to federate with ship's carpenters of Tokyo, Kobe and Osaka. I will write fully upon the subject in my next letter to you.

In other words, Fusatarô and his friends were advising the Yokohama ship carpenters in their strike that was developing in an orderly manner. This strike was the first of the activities of the Friends of Labor in Japan, and it can be surmised that the trigger for it was Fusatarô's Call to All Workers. Fusatarô's diary provides some evidence for this:

June 10 (Thurs.)

Today Jô came. He asked me to go to Yokohama tomorrow.

June 11 (Fri.)

9.45 a.m. Went to Yokohama with Jô. Met Ôsawa there. Took a train [steam train - transl.] back to Tokyo at 4 p.m.

June 20 (Sun.)

...11.10 a.m. Took a train to Yokohama and went to the shipyard. Went to the ironworks and was taken to the ship carpenters' office by Mr. Ôtegawa's wife. I asked about the strike. On the way back I visited Mitsubori, and Ikai and Tsunoda also came. At 8 p.m. took a train back to Tokyo.

June 26 (Sat.)

... 7 a.m. took a train to Yokohama.

June 27 (Sun.)

This morning visited the ship carpenters' union. Visited Mr Miyata and other people.

July 1 (Thurs.)

Left home at 8 a.m. and went to Sawada's. With Jô, Yoshida and others, went to Yokohama, went to 99 Bankan, on the way back I visited the office of the ship carpenters' union. Returned home on the 5 p.m. train.

The reason why Jô Tsunetarô asked Fusatarô on June 10 to go to Yokohama, was probably because on that same day or the day before, Jô was visited by members of the Yokohama ship carpenters' union. At the conclusion of the Call to All Workers are the following words:

If enquiries about the method of forming a union, of establishing union rules, of sustaining a union and other related details are addressed to the Friends of Labor, they will carefully explain such matters and according to the situation, render the appropriate assistance.

The address of the Friends of Labor, which was at that time Jô's address, would most likely have been printed on the back of the pamphlet.

The first and the last public meeting organized by the Friends of Labor

Fusatarô, who had very likely encouraged the ship carpenters in their strike, turned to fresh campaigning activities on his return from Yokohama. The goal was a proper 'public meeting under the auspices of the Friends of Labor'. Before reporting to Gompers that the Friends of Labor had organized and put on such an event, Fusatarô clearly felt that it was necessary for the group to do this themselves at least once under their own name. This was a turning point for him; his casual lifestyle ended, and his busy days began.

If they were to hold such an event, they first had to attend to the costs involved and the speakers to be invited. The costs of the hall hire and publicity amounted to over 20 yen. For comparison, the starting salary for a primary school teacher in those days was 8 yen a month. Next, they had to secure the services of speakers who recognized the importance of the labor union movement and who would speak for free. There were only four members of the Friends of Labor, and there were concerns, given the restricted circle of their acquaintances, about the extent of the appeal they would be able to make to the public. They would have to rely on speakers who could draw audiences.

On the question of finances, Fusatarô and the members of the Friends of Labor really put all they had into the venture. Fusatarô himself had just finished writing Practical English-Japanese Business Conversation (Jitsuyô Eiwa Shôgyô Kaiwa) for which he had been paid 50 yen, and this would certainly have come in useful.

Fusatarô's diary records the process of securing the hall and the speakers.

June 12 (Sat.)

This afternoon visited Mr. Katayama and obtained his agreement to take part in the lecture meeting; went to the Seinenkai, met Mr. Niwa and requested the rental of the hall for the 5th; visited Mr. Matsumura Kaiseki and obtained his agreement to participate in the lecture meeting.

June 17 (Thurs.)

8.30 a.m. called on Mr. Sakuma and secured his agreement to take part in the lecture meeting. Then I asked him to get Shimada to attend. On the way home, I visited Jô then went to the Tokyo Industrialists Association office. Returned home at 3 p.m.

June 20 (Sun.)

9 a.m. called on Mr. Sakuma and asked about Shimada's reply. It seems he cannot attend.

June 21 (Mon.)

Called on Mr. Jô in the morning, but he was out so visited Mr. Higashida of Hakkanchô and met Mr. Jô there, consulted Mr. Sawada, and on the way back, called at the Seinenkai and met Mr. Niwa and confirmed the hire of the hall for the 25th, then called on Mr. Hara Taneaki and asked about Mr. Katayama. After discussions with Hara, returned home. In the evening Suzuki Jun'ichiro came by, and I received payment for the conversation book I wrote for Ôkura Publishing Co.

Preparations for the public meeting began on June 12. That day, application was made to hire the venue, and 'Mr Katayama' and Matsumura Kaiseki were asked to participate as speakers. This 'Mr Katayama' was, of course, Katayama Sen, and this was the first meeting between him and Takano Fusatarô. I shall only lightly touch on Katayama Sen here, as we shall be looking in detail many times from now on in this book at the man who was to become alongside Fusatarô a leader of the labor movement. Katayama had studied in America at about the same time as Fusatarô had been there. A Christian, he had returned to Japan after gaining two university degrees in literature and theology and in the Kanda Misakichô area of Tokyo he had just opened a social enterprise institute named 'the Kingsley Hall'.

The 'Seinenkai' referred to was the Tokyo Christian Youth Association, in other words, the YMCA, located in Kanda Mitoshirochô. 'Niwa' Seijiro was the secretary there and also the accountant at the Kingsley Hall. The Kanda YMCA Hall was a three story red brick building that had been built just three years before with the support of American Christians. It had been designed by Josiah Conder, known also for his designs of the Holy Resurrection Cathedral (popularly known as the 'Nikolai-do') and the Rokumeikan, the Deer Cry Pavilion. The YMCA was a landmark of Kanda, a large hall, the only large-scale assembly hall in Tokyo. It could accommodate well over a thousand people and was lit by electricity, which was still a novelty at that time.

Matsumura Kaiseki was a Christian who had studied at Yokohama's Hepburn seminar and the Itchi Theology School at Tsukiji, in Tokyo. He had been a minister at the Takahashi Church in Okayama Prefecture and vice-principal of the Yamagata English School and the Hokuetsu Academy in Niigata. In 1897 he was an instructor at the Tokyo YMCA and a member of staff at the Kingsley Hall. Rather than being Christian sermons, Matsumura's speeches on spiritual themes which focused on classic heroes of the East and the West had made him a well-known figure, and he was a famous lecturer at the YMCA where every week hundreds of fans gathered to hear him lecture.

On June 17, Sakuma Teichii was asked to participate, and he agreed. A friend of Sakuma's since his youth, Mainichi Newspaper president and Dietman Shimada Saburô, was asked to moderate the meeting, but this did not come about. Suzuki Junichiro was also asked to be a speaker, but on the night of the event he was ill and could not attend.

In the end, five speakers took part: Jô Tsunetarô and Takano Fusatarô from the Friends of Labor, Matsumura Kaiseki, Sakuma Tei'ichi, and Katayama Sen. Jô gave the opening address, then came Takano whose theme was "Japanese Workers and American Workers"; Matsumura's title was "The Dawn of Hope"; Sakuma spoke on "Stokers' Problems", while Katayama's topic was "The Need for Workers' Solidarity". Looking at the build-up to the event, one is struck by how effectively Fusatarô and his colleagues prepared for it in such a short time, given that they were unfamiliar with campaigning in Japan. Their experience with Dokôkai in Yokohama most likely played a part. The event turned out to be a great success. Fusataro wrote a report of it in a letter to Gompers (July 30, 1897):

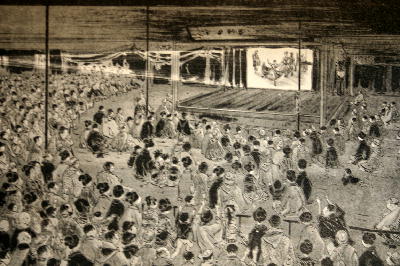

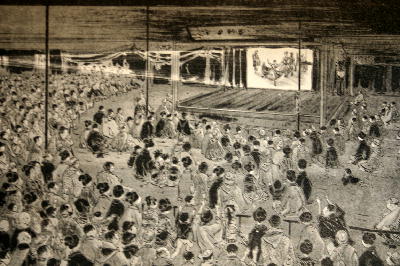

I have the greatest pleasure to announce to you that the "Friends of Labor" succeeded again to hold a public meeting and it proved, I am glad to say, a great success. The meeting was held at the hall of Young Men's Christian Association at Kanda on the evening of June 25th. We had element against us again but over twelve hundred workingmen of various trades attended despite the rain and muddy road. The meeting was addressee by Messrs. Geo, a member of the "Friends of Labor," Rev. Kaiseki Matsumura, lecturer of Y.M.C.A., Tei'ichi Sakuma, well known capitalist and sympathizer of working people, Sen Katayama, a graduate of Harvard University and myself. Never before such a great assemblage and enthusiastic meeting of working people held in this country; great applause and prolonged hand clapping was "the order of the day." Every utterance of speakers in connection with deplorable condition of working people and advice of united action on the part of them brought the whole house to an enthusiastic applause.

In view of the fact that this was written following his previous letter in which he had told the untruth that the Lecture Meeting had been held under the auspices of the Friends of Labor, all the more does the credibility of this report need to be regarded with some doubt. However, the Mainichi Newspaper reported on the same event that over 1,500 people attended, some 300 more than in Fusatarô's letter. When one bears in mind that just ten days after the meeting, the Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai (Society for the Formation of Labor Unions) was founded, then Fusatarô's letter is unlikely to have been hyperbole.

Public Meeting on Labor Issues

The public meeting was held last night the 25th at the YMCA Hall in Kanda. It was a rainy day but despite the muddy roads, the audience numbered over 1500, more than half of whom were workers. The hall opened at 7 p.m. Mr. Jô Tsunetarô gave the first address, explaining why the avoidance of strikes actually served to strengthen workers' solidarity. Next was Mr.Takano Fusatarô, who, we heard, was the representative of a North American workers' organization [AFL]. He gave a detailed comparison of workers' wages in America and Japan. He made much of the fact that whereas they were all workers, Americans' wages were much higher while wages in Japan were exceptionally low. He argued that it was vital that Japanese wages should be much higher to enable Japanese workers to have a decent human livelihood. He was followed by Mr. Matsumura Kaiseki, who called for raising workers' status through education. Mr. Sakuma Tei'ichi was the fourth speaker. He spoke about a stokers' strike on a transoceanic mail ship, in which there had been all kinds of violent behavior and as a result, the trust of foreigners had been lost and had caused Japanese workers to lose face in their eyes. He went on to say that the first step in improving such bad habits among workers should be to determine regulations and to establish unions. If this were done, workers' wages would rise, workers would be educated and various forms of violence would decrease. The speaker left the stage to thunderous applause. Finally, Mr. Katayama Sen spoke on the need for workers' solidarity, after which the meeting closed at 10 p.m.

An audience of well over 1000 people had assembled despite the rainy weather, and their response to what they heard was of great enthusiasm. Fusatarô now decided on his next step, and at the end of the meeting, he called on all those interested to remain behind in the hall; 40 people did so. It was decided then and there that in a few days' time, the founding meeting of the Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai would be held, and with that, the first and last public meeting organized by the Friends of Labor came to a most successful end.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), Chapter 8 Shokko shokun ni yosu

|