Chapter 11 Why artisans' unions did not join Kiseikai

- Qualifications in the West, experience in Japan -

Why did other unions not join Kiseikai?

Naturally, Kiseikai was not satisfied by the formation of the Ironworkers' Union. It called on other groups of workers to form their own unions and tried to get existing unions to join Kiseikai. The argument was made in an article in the 1899 New Year issue of The Labor World - "Form large labor unions all over the country" (Zenkoku dai-rôdô kumiai wo kessei subeshi) and another in February "Organizing labor unions throughout the country" (Zenkoku rôdô kumiai wo soshiki suru no gi). The urgnet task was to gather all existing unions within Kiseikai.

The union that was the most likely to join Kiseikai and which had been expected to associate itself with Kiseikai's rapid ascent was the Nittetsu Kyôseikai (Society for the Correction of Abuses of Japan Railway Company). Fusatarô reported in a letter to Gompers that Kyôseikai was soon likely to join Kiseikai and some members of Kyôseikai had already joined Kiseikai on an individual basis. During his speaking tour of northern Japan (which will be discussed later), Kyôseikai members provided funds and organized some speaking engagements for him. Beginning with its sympathetic reporting of the Nittetsu strike, The Labor World frequently carried reports on developments in Kyôseikai and the Japan Railways Company.

But there was a powerful group within Kyôseikai that opposed joining Kiseikai, and a proposal to join was rejected at one of its conferences. The reason is unclear, but it is likely that Kyôseikai, which had been formed soon after the victorious great strike, had a strong sense of self-respect and could not countenance formal union with another organization such as Kiseikai. There would have been Kyôseikai members who would have opposed the merger, pointing out that as their union had built up funds of 20,000 yen, much more than Kiseikai, and was in a better financial position, becoming a subgroup of Kiseikai would restrict their freedom and increase their financial liabilities. The management of the Japan Railways Company also worked against any collaboration between Kyôseikai and Kiseikai, fearing that it would represent a dramatic increase in union power within the company.

The Printworkers' Union had its connection to Sakuma Tei'ichi and so had a close connection to Kiseikai. Printworkers were the second most numerous group in Kiseikai after ironworkers, and their own union (Kappankô dôshi konwakai - Typesetters' Fraternal Society) was formed in 1898 with the support of Kiseikai. The Typesetters' Union, the transformed from the Fraternal Society, chose as its head Shimada Saburô, an old friend of Sakuma Tei'ichi and a Kiseikai Council member. Takano Fusatarô and Katayama Sen were invited to speak at the two unions' meetings, and it was of course expected that the Typesetters' Union would become a strong participant in Kiseikai.

However, when Katayama Sen had occasion to criticize some of the members of the Typestters' Society, relations between the two groups soured. They then developed into a real split when a row broke out over differing interpretations of socialism at a Typesetters' Union speakers' meeting between Katayama Sen and the Social Policy Association members. At the meeting Kanai Noburu and other members of the Social Policy Association strongly criticized what they saw as the inadequacy of Katayama's understanding of socialism. Katayama then wrote a fierce response in The Labor World. This was followed by the death of Sakuma Tei'ichi, after which employers of the printing company took a harder view of unions and began to see them as enemies. This stopped the development of printworkers' unions, and the very existence of the unions was threatened, let alone the question of combining with Kiseikai.

Qualifications in the West, experience in Japan - why artisans' unions did not join Kiseikai

We shall turn now to the question raised earlier, why, apart from the ironworkers, did other groups of workers not join Kiseikai? Takano Fusatarô had orignally expected that traditional artisans' groups, such as the carpenters' unions, would join Kiseikai. It was understandable that he should think so, as in the West the early labor movement had been led by groups in the building trades such as carpenters and stonemasons. In February 1896, when he was still serving on a US warship, Takano had written to Gompers that "I found upon a brief investigation, a strong labor union existing in this city which, in its every aspect is a best type of union to be hoped for in the present condition of the Japanese workers. I refer to the Tokio Carpenters' Union."

This expectation is reflected in "A Call to Workers" (Shokkô shokun ni yosu), which as an actual example of a labor union, refers directly to the carpenters' union. With this expectation in mind, in his speeches to the Tokyo Industrialists Association's General Assembly, the Filemakers' Union, the Tokyo Ship Carpenters' Union and the Tokyo Dollmakers' Union, Fusatarô worked to get the leading artisans' groups to join Kiseikai. But none of the unions in these trades did join. Moreover, few individual artisans joined either. The total of 2,717 Kiseikai members at the end of 1898 included only 17 ship carpenters and 3 dollmakers.

Why did Japan's artisans, either in their unions or individually, show so little interest in joining Kiseikai? The main reason was that most of the unions in these artisans' trades did not regard themselves as workers; rather, they were organizations in which there was a strong inclination to regard themselves as entrepreneurs and owners.

In the West, since the Middle Ages, guilds had monopolized traditional craft industries, and to regulate competition among the members, customs had been consolidated that would protect the interests of the craft trades. The most strictly enforced of the rules to regulate competition were "the rules of entry to the craft". To become a full member of the guild, one had to serve as an apprentice to a master craftman for a certain number of years, then as a journeyman for several years, and after that one had to gain recognition by all guild members. The number of apprentices that one master could take was regurated and further the total number of masters was restricted. So the situation arose whereby many, on completing their apprenticeship, had to work all their lives as journeymen without being able to become masters themselves. These men then formed journeymen's guilds on the model of the masters' guilds, and a movement developed whereby these journeymen's guilds would negotiate terms with the masters' guilds over mutual cooperation, higher wages and shorter working hours. It was these 'journeymen's guilds' that were the model for the 'craft unions' that ought to be seen as the origin of the labor movement in the West.

The basic statutes of the craft unions too, like those of the guilds, strictly regulated members' qualifications and the number of members. Full membership was only available to those who had completed a fixed term of apprenticeship under another full member. The length of the training varied over the years and in the different trades but was normally between 5 and 7 years and had to be completed by the time a man was 21 years old. Even if one had the necessary ability for the trade, anyone who had not properly completed the requisite formalities could not become a member of the union. In other words, the 'skills' of 'skilled workers' organized in craft unions were defined not by the actual 'ability to do the job' but by the possession of 'qualifications' obtained after going through the correct formalities. However, in Japan, such a 'qualification system' had not existed until, along with the introduction of the school system, a system of state-recognized qualifications was established for doctors and lawyers. In contrast to the societies of the West, Japanese society was one in which 'practical skill', 'the ability to do the job' was more highly regarded.

Every country has 'an apprentice system' to enable skills to be passed on so that a new generation of craftsmen can be trained and usually, an accompanying craft organization of some kind. In Japan too there had long existed such associations in which craftsmen working within the same trade sought to protect the interests of their craft. Carpenters, stonemasons, plasterers and others in the building trades had formed their own groups called taishikô to assist each other. Unlike the West, there were in Japan no trade groups that enforced 'entry rules'. If one had the skills to do the job, one was recognized as a proper craftsman. There were no conditions in Japan making for the emergence of journeymen's unions that were separate from those of master craftsmen; masters and journeymen both belonged to the same organization.

Why did Japanese craft groups differ in character from those in the West? The disparity stemmed from the difference between Japanese towns under the feudal clan system and mediaeval cities and towns in the West. Western cities and towns were generally autonomous communities ruled by the masters of the guilds. The whole society within the city respected the autonomous rules of the craft guilds. By contrast, in Tokugawa period Japan, urban communities were mostly castle towns (jôka machi) under the authority of feudal lords. In castle towns no organization could exist that was not recognized by the feudal lord. Of course, craft groups and commercial groups organized themselves according to their own occupations in order to protect their own interests. Various overlapping efforts were frequently made in this direction, which resembled the activities of western guilds, such as territorial demarcation arrangements to prevent too many tradesmen operating in the same area.

Another important factor is that mediaeval European society, especially urban society, was highly legalistic. This influenced the importance placed on documents, written qualifications etc. This was the heritage of abstract intellectual thinking that the Church had carried over from classical Greco-Roman times, and it permeated European society, from documentation relating to the property rights of the nobility and the Church through to the rights and responsiblities of corporations, universities and guilds. Such legalism was already well in evidence by the time of Magna Carta (1215), for example, and tended to become ever more complex through the Middle Ages as European societies developed their forms of bureaucracy, national and local, and lawyers became ever more numerous.

Whereas like Japan, in a society which felt that 'as long as you have the skill, you're fully qualified man' (ude sae areba ichi'nin-mae), there were bound to be many outsiders who did not join the fellowship of the tradesmen's groups (nakama) and it was impossible to make them conform to the norms of those nakama. What frequently happened as a result was that the nakama offered money or submitted to work by appointment to the feudal lord without financial compensation, and in return, the feudal lord would control the outsiders and force them to join the nakama. The artisans thus sought to protect their occupational interests not through their own autonomous efforts but through the intervention of a higher authority.

Meanwhile, the shogunate and the feudal lords would from time to time, in accordance with their policy aims of securing stable prices and tax revenues, order tradesmen to form new trade associations or else to dissolve existing ones. The Meiji government did not recognize the existence of nakama and prohibited them from trying to regulate the price and quality of goods. In a society in which the formation of occupational associations was ruled in this way, autonomous occupational associations simply could not exist, while with outsiders being beyond the pale, occupational groups that had the power to make and enforce their own rules could not develop.

In his Nihon no kasô shakai (The Society of Japan's Lower Classes), published in 1898, Yokoyama Gen'nosuke lists 66 trade associations and goes on to make the following observation:

But what does the internal organization of these unions actually amount to? Many of them are unions in name only; in formal terms, they hang out their signs and meet once or twice a year. Or perhaps they do not even meet. Only the names of the unions previously mentioned remain; there are those which today hold no meetings at all. Of the artisans' groups, I heard that the carpenters, who are the top-ranked group and are the most numerous, had an association until seven or eight years ago, but now there is only a small group in Hongo ward and apart from that, neither hide nor hair of any others. This is the present state of things in the trades community.

Why these trade associations had become all form and no substance was because the key members, the masters (oyakata) sought to be contractors themselves and were competing against each other. They did not think of themselves as workers and would not have dreamed of joining Kiseikai, and/or of organizing themselves into labor unions.

Among the unions of skilled workers, those which had a relatively strong sense of being workers were the miners, and the ship carpenters who were employed in shipyards. But these unions too did not try to control the labor market like craft unions by means of 'entry regulations'. 'As long as you have the skill, you're fully qualified man' (ude sae areba ichin-mae) was the rule, and even if apprentices had not completed their term of training, if they could just about manage to do the job, it was quite normal for them to leave their oyakata and work for another one who would pay them more. In Western craft unions, if a employer were to try to hire a non-union man who had not completed his training as an apprentice, other union members would refuse to work, saying "we're not working with unqualified men". This attitude was firmly held to by skilled workers and the statutes of many unions forbade their members from working with non-union men. But in Japan, this attitude and practice did not exist. Even if groups had a strong consciousness of themselves as workers, such as the mineworkers' unions (tomokodômei) and the ship carpenters' unions, the most they could do was to 'provide the muscle' in labor disputes.

The Ironworkers' Union was not an occupational union

At this point, we need to make clear to ourselves once again that, although many books describe the Ironworkers' Union as an occupational union, this is an error. The Ironworkers' Union was a completely different organization from the craft unions of the West. What made it so different from the craft union was the fact that the qualification for becoming a member was so very loose. Clause 6 of the union's statutes states the following:

Machinists, blacksmiths, boiler makers, foundry workers, model makers, copper workers, steel shipbuilding workers, electricians, locomotive drivers and stokers employed at ironworks, who, in accordance with the formalities stated elsewhere, apply for admission to the head office or to a branch office and who are recognized by a union officials' meeting, will be admitted as members of this union.

In other words, the Ironworkers' Union was not restricted to particular occupations but sought to organize all those who worked in engineering and metalworking factories and shops. Most members were ironworkers (tekkô) - machinists, blacksmiths, boilermakers and foundry workers - but membership was also open to those who were not ironworkers, such as woodworkers, painters, steam engine operators and stokers. There were of course no regulations stipulating 'qualifications' related to fixed terms of apprenticeship; that was not an issue. It was not therefore an occupational union but an industry-wide, or industrial union open to all metal and engineering workers. However, although it was indeed an 'industry-wide union', it was not the kind of industrial unions referred to in industrial relations textbooks. For the Ironworkers' Union, to have been able to engage in collective bargaining with management about working conditions would have been beyond its wildest dreams. To put it another way, the Ironworkers' Union did not fit into the categories of unions that one finds in textbooks on industrial relations. In other words, there is no point in applying to the Ironworkers' Union the criterion of 'an organization that sells labor power', which is normally emphasized as the key characteristic of a labor union. For good or ill, that was the real nature of Japan's early 'labor unions'.

Fusatarô and his colleagues imagined that in the future, Japanese unions would become occupational unions as in the West, but the actual situation of the Ironworkers' Union was that it was an organization for all those who worked at workplaces and factories in the metal and engineering industries and who wanted to help, support and learn from each other, and raise their status in society. To put it still another way, it was both a social campaigning group to raise the social status of industrial workers and at the same time, a fraternal association that sought to provide mutual aid for its members.

The Government orders a ban on Kiseikai's Grand Sports Meeting

There were among the ruling class individuals such as Hino Sukehide and Kaneko Kentarô who showed an understanding for the labor movement. However, those in the Ministry of Home Affairs who were tasked with the administration of the police and who had consistently resorted to a repressive policy looked on popular movements and voluntary societies as seedbeds of opposition to the establishment. They harbored strong feelings of apprehension about Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union, and both overtly and covertly, worked to block the labor movement. Nevertheless, in the early years, soon after the movement had got underway, the government had not yet consolidated its policy with regard to it. This was why technicians from the army arsenal were present at the founding of the Ironworkers' Union.

However, the issuing by the Metropolitan Police Office on April 1, 1898 of an order banning Kiseikai's Grand Sports Meeting clearly showed that the policy of the Ministry of Home Affairs police bureaucracy was not one of non-intervention but of repressive interference. The plan for the Grand Sports Meeting of April 3 had been to march from the Eirakuchô fields in Gofukuchô, close to the Kiseikai head office, to Ueno Park and after cherry blossom viewing and having lunch there next to the museum, to hold a sports meeting. On the surface of it, it looked like a pleasure outing. However, the organzers had May Day celebrations in mind and modelled the gathering after that pattern. The Labor World named the day the Grand Memorial Labor Day (dai rôdô kinenbi) and reported it as 'Labor Day' in its English language columns. Its enthusiasm was evident in the sentence: April 3 will be a grand festive occasion for our nation's labor movement and will deserve to be commemorated as such in history for ages to come. Adults were charged 30 sen to take part and children 5 sen; they were to be given a matching hat and badge to wear, form ranks and march with banners waving and a band at their head.

Suzuki Jun'ichirô planned to have everyone sing a popular miritary song "Teki wa ikuman aritotemo" (However many tens of thousands the enemy may number), to which he added the lyric "The great Mt Fuji which towers up to heaven is still but one great lump of earth". That day was a holiday, Jinmu ten'nôsai, the Festival of the Emperor Jinmu, which commemorated the death of the first emperor of Japan, and many factories, including the military arsenals, had the day off. It was therefore intended to use the opportunity to promote amity among the members and to show off their strength and vigor.

After the plan was announced in The Labor World, on March 23 the Nihombashi Police Office summoned Takano Fusatarô and advised him that "the Metropolitan Police Office is not disposed to grant permission for this plan, and it would be advisable to cancel the event forthwith". Taken aback, Fusatarô replied that "we are not planning any disturbance. Why is it being prohibited?" and went straight to Sakuma Tei'ichi, explained the situation to him and asked for his support. The following day, Sakuma, a member of the Tokyo City Council, called at the Metropolitan Police Office and met with police detective Kawata Masane and later said that he had "explained the nature of Rôodô Kumiai Kiseikai and declared that the apparent attempt to repress the movement was completely ill-advised." In response, detective Kawata had said that "if Mr Sakuma could guarantee that the sports festival would be no result in making high spirits among workers in the future, then permission could be given for the event." The following day, Fusatarô himself went to the Metropolitan Police Office and had an interview with Detective Kawata at which he explained what Kiseikai was and said that if it could be explained to him what the problem was, and told what changes needed to be made in order for permission to be granted, he would do everything to effect those changes, but Kawata merely replied that he had asked his superiors and had been told to await further instructions. Kiseikai duly waited but by the end of March no 'further instructions' had been received. In the meantime Kiseikai judged that the police authorities's might fear the event would make the workers spirits high, then marching of the large number of workers through the streets would represent a serious problem and that if the march were banned, then the people could gather in Ueno Park in small groups and hold their sports day there; they proceeded to make their preparations with these two possible scenarios in mind. On April 1 the application to hold the sports meeting on the 3rd was handed in at the Kojimachi Police Station but soon afterwards the order banning the event was issued and even gathering in Ueno Park for the sports meeting was also prohibited. Lunches for 1,500 people, the arrangements with the three bands and all the hats and badges - all came to nothing.

What concerned Fusatarô and his colleagues was the impression given to society at large that workers' unions could not gather peaceably, and they were anxious to resolve the problem calmly. The Labor World published several articles which addressed this issue, and one of them, included the section entitled "the stance that the Rôdôkumiai kiseikai should adopt in the face of police repression" and the following words:

We recommend, in accordance with thoroughly pacifist principles, the resolve to hold to those principles to the bitter end, bearing any difficulties and all the false charges society may lay against Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai.

Nevertheless, on April 10, a week after the original plan, an unexpected opportunity enabled the Kiseikai Grand Sports Meeting to go ahead. That day was a national holiday held to commemorate the 30th year since the transfer of the site of the capital from Kyoto to Tokyo, and various groups carried out celebratory processions. Kiseikai took advantage of this opportunity to parade through the streets and hold its sports meeting, by which it was able to wipe away the unhappiness over the banned Grand Sports Meeting.

The 'soot-stained' squad of activists - Campaigning in the Tôhoku region

Eight days after July 23 1898, Fusatarô went a speaking tour of the Tôhoku region in the north. It was the first region he and his colleagues had visited for this purpose and they were given such a tremendous welcome wherever they went that it turned out to be an unforgettable trip. Unusually for Fusatarô, he recorded some of the details of the trip in a series of articles in The Labor World. There were four people in the group: Fusatarô, Katayama Sen, Takahashi Sadakichi, a founding member of the Ironworkers' Union, and Ogasawara Kentarô. Takahashi Sadakichi was a foundry worker at the Tokyo Arsenal, who had himself bought 40 copies of Kiseikai pamphlet Rôdôsha no kokoroe (What Workers Need to Know) and had been an ardent member since the founding of the union.

Within Kiseikai a 'Young Speakers Group' was established, which frequently appeared at public meetings and became known as the 'The Worker Orators'. Ogasawara Kentarô belonged to No.6 branch of the Ironworkers' Union, so he was a factory worker from the Honjo region. At Kiseikai he worked on the accounts.

The Tôhoku speaking tour dates and locations were as follows; apart from the last day, these were all locations where public meetings were held:

July 23 Ômiya

24 Fukushima

25 Ichinoseki

26 Morioka

27 Aomori

28 Shirinai

29 Sendai

30 Utsunomiya

31 Return to Tokyo

By today's standards, it may not seem like such a substantial tour, but when one looks at the train schedule one realizes it was a tough daily effort. For example, today, it takes about one hour ten minutes from Ômiya to Fukushima, but at that time, one would get on the train at 6 a.m. and arrive at 4.30 p.m. - a journey of 10 hours! Fusatarô wrote of this as follows:

Shut up in a railway compartment under a hot sky, one wished for a draught of wind but there was only gusts of sand constantly swirling about one, so that one had sand and soot everywhere - face, hands, feet, and skin.

It was an age without air-conditioning, so windows had to be left open, but then soot and coal dust were bound to be blown in. Once arrived at their destinations, they had meetings with ironworkers and Japan Railways train drivers, public meetings and social gatherings - a very full schedule that ended only deep into the night. This went on for eight days.

This Tôhoku speaking tour was the result of a proposal made at a monthly meeting of Kiseikai in May. It was reported in issue No. 14 of The Labor World:

At the 11th monthly meeting of Rôdô Kiseikai on the evening of the 29th of last month held at Yanagiya in Nihombashi Gofukuchô, a proposal to expand the affairs of the union was discussed and gained the approval of most of those present. It was enthusiastically resolved to raise funds from the membership for the movement. The reason for this, we have heard, is that at the meeting, the need for regional speaking tours was vigorously advocated....

On the basis of this decision, the membership was called on to contribute to campaign funds for regional speaking tours and by the end of the year, 186 yen 42 sen had been contributed. Costs for the 'Tôhoku speaking tour' (train fares, accommodation, public meeting costs etc.) eventually worked out at 76 yen 18 sen 5 rin.

From the outset Kiseikai had always aimed to be a national organization, and regional speaking tours had long been intended. But why was the Tôhoku region selected as the destination for the first such tour? One might think that the Hanshin region of western Japan, where industrialization was well underway, would have been chosen.

There was in fact a particular reason for the choice. It was because of the famous "Japan Railway Company locomotive drivers' strike" that had taken place in February. Japan Railway Company (Nihon Tetsudo Gaisha) was known by the abbreviated form of its name, as 'Nittetsu'. It was a private company, but at the time it far outstripped the national railways and was the largest railway company in Japan. It operated within the limits of today's East Japan Railway Company's Tôhoku, Takasaki and Jôban lines and employed a workforce of 10,000. The drivers and stokers at Nittetsu formed a secret organization known as Great League for the Better Treatment of Workers (Wagatô taigû kisei daidômeikai) and campaigned for better treatment and conditions. Their demands were (1) better status within the company (equal status with office staff); (2) a change of job nomenclature (from kikankata [locomotive driver] to kikanshi [locomotive engineer; the character for -shi in kikanshi literally means 'warrior' - transl.) and from kafu (stoker) to norikumi kikansei (probationary engineer); (3) higher wages. Every worker in each engine depot sent these demands by post to the company, and as a tactic in the dispute, started a 'work to rule dispute' in accordance with Article 333 of the Public Service Regulations. This stipulated that even if a train was late it was not to be driven at high speed, which led to delays at every train stop.

In response, the company first resorted to heavy-handed tactics. It tried to crush the action by laying off the ringleaders Ishida Rokujirô and Yasui Hikotarô. The drivers responded by contacting each other by telegraph and on the evening of February 24 entered into a full-blown strike: all trains stopped running, from Ueno (in Tokyo) up to Aomori. Because the strike showed signs of spreading to other railway companies, the management gave way and finally agreed to talks, which resulted in most of the strikers' demands being met. However, after the strike, the Nittetsu drivers succeeded in establishing the Nihon Tetsudô Kyôseikai (The Society for the Correction of of Abuses at the Japan Railway Company).

This was a great opportunity for Kiseikai. If they could get Kyôseikai to join Kiseikai, the organization could expand rapidly. With this in mind, The Labor World published an editorial aimed at locomotive engineers and titled "Hopes for the Establishment of an All-Japan Railwayworkers' Union", and Fusatarô called on Kyôseikai to progress towards a great combination of all the nation's locomotive engineers. He had always been very interested in railway workers' unions and in New York he had even exchanged letters with various rail unions that did not belong to the AFL.

The locomotive drivers' dispute influenced the other workers employed by Nittetsu. At the Ômiya Works the No.2 Branch of the Ironworkers' Union was already in existence, and advantage was taken of the strike to unionize other ironworkers at engine depots in various other locations. First to join were the ironworkers at Fukushima Depot, Kuroiso Depot and Sendai Depot, and on May 25, No.23 Branch was established. The speaking tour in Tôhoku was intended to respond to the wishes of the workers in the depots in the various locations throughout the region.

The successful results of the Tôhoku speaking tour can be seen in the fact that soon afterwards, on August 5, No. 25 Branch of the Ironworkers' Union was founded at the Nittetsu Aomori Works and on the following day, No. 26 Branch in Morioka Works got underway.

The movement for the revision of the Factory Bill

In the autumn of 1898 Fusatarô turned to put all his energies into the campaign to revise the Factory Bill and became so heavily involved in this that he did not even have time to reply to Gompers' letters. The Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce had drawn up the Factory Bill for presentation to the Imperial Diet and had requested for advice to the Agricultural, Industrial and Commercial Higher Council. The Factory Bill was intended to be legislation that would safeguard workers' welfare by banning child labor, limiting working hours for minors and women, prohibiting night-time working and requiring factory owners to provide compensation schemes for injuries sustained at work. Scholars and bureaucrats had recognized the need for such legislation early on, but owners had put up stiff resistance, and in the end it did not actually pass until a few years later, in 1911, and even then its implementation was delayed until 1916.

The Agricultural, Industrial and Commercial Higher Council was set up after the Sino-Japanese War as an consultative body of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce in the area of economic policy. It had some 30 members, most of whom were leading capitalists such as Shibusawa Eiichi and Shôda Heigorô. Temporary members included bureaucrats such as Soeda Juichi and scholars such as Kanai Noburu, Professor at the Imperial University. In September, before submitting questions to the Higher Council, the Ministry published its draft proposals for the legislation and sent questions to Chambers of Commerce around the country. There were still no national organizations of factory owners; the only organizations were regional chambers of commerce, which represented local industrialists.

Kiseikai had from its outset called for the passing of trade union legislation and factory Laws and at its monthly meeting in September it examined all aspects of the draft legislation. The members were greatly interested in the Factory Bill and many of them attended the meeting, as well as a number of observers. Sakuma Tei'ichi, who was both a Kiseikai council member and a member of the Agricultural, Industrial and Commercial Higher Council, spoke and then the members assessed the draft legislation, concluding that eight aspects required revision. Fusatarô and five others were selected to form an appeal committee and tasked with presenting an appeal for revision. The eight aspects requiring revision were:

(1) There were many issues in smaller factories relating to factory hygiene and long working hours, so the original draft proposal that defined small factories for the implemenation of the Factory Law should be expanded from "workplaces where 50 workers and apprentices are employed" to "workplaces where various types of workforce, and five or more workers and apprentices".

(2) The extenuating clause that provided for the employment of children under ten years of age "in special cases" should be omitted and employment of such children recognized in no cases.

(3) According to the draft legislation, workers under the age of 14 were not to work "more than 10 hours a day" should be revised to "no work for more than 8 hours a day in any circumstances."

(4) Working hours should be limited for workers over 14 years of age to no more than 10 hours a day. However, in extraordinary circumstances, extensions can be allowed with the permission of factory inspectors.

(5) Rest days should be given once a week rather than twice a month.

(6) Factory owners should be under obligation to provide education to workers under 14 who had not completed elementary school; offenders should be subject to a fine of 200 yen.

(7) The draft legislation absolved factory owners of the obligation to pay the costs of funerals and support if workers were injured or killed following the directives of third parties just as they were absolved in the case of workers' death or injury due to their own actions or due to disasters and natural calamities. This should be amended to obligate factory owners to pay funeral costs and support in the case of death or injury following the directives of third parties.

(8) Employment certificates should be required only in the case of apprentices.

Of these eight proposals, the last one needs further explanation. The obligation to produce written evidence (shokkôshô), a certificate stating that one was a factory worker, was introduced into the bill under pressure from employers as a means of preventing workers from quitting. What the measure would have entailed was that workers in designated occupations would have had to carry such written evidence and it would be illegal to hire those that did not. The employers would keep the certificate for the duration of a worker's employment and return it when he was laid off. Kiseikai was opposed to this on the grounds that it obstructed a worker's freedom of movement. In those days there were many workers who moved from firm to firm in search of higher wages. This had become a cause of acute concern among workers, which was the reason why this clause was included among the demands for revision of the draft legislation.

Those selected to serve on the appeal committee were Takano Fusatarô, Ozawa Benzô, Nagayama Eiji, Katayama Sen, and Sawada Han'nosuke. It was not the case that all of them acted as a group; those who could would get together when they had time to do so; only Fusatarô was able to be constantly on the move and engaged in all activities. A series of reports in The Labor World illustrates the actions of the committee:

October 3 (Mon.)

First campaign. The appeal committee called on Mr. Ariga, Head of the Factories Office at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce and submitted the appeal. Shimada Saburô was then called on at his home in Kôjimachi, and opinions on the need for revision of each article were explained to him. The residences of Shimura Gentarô and Hotta Rentarô were both called on but the two men were not at home. Sakuma Tei'ichi was then called on. He was in bed with a serious illness but listened to the appeal committee members' explanation of their views on the need for revision and encouraged them in their efforts. Taguchi Ukichi was then called on at the Keizai Zasshi sha (Economics Magazine Co. ; publisher of the Tokyo Keizai Zasshi) but he was out. A call was then made on the Home Affairs Minister Itagaki Taisuke at the Ministry for Home Affairs but he was said to be on the point of leaving office, so instead, the committee met with a Senior Clerk of the Ministry, Mr. Matsui, and explained the issue to him. Visits were made to the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce to meet with Shibusawa Eichi and Nakano Buei. Shibusawa was absent on account of illness, and Nakano was in a meeting, so the case was explained instead to Hagiwara Gentarô, Chief Secretary at the Tokyo Chamber of Commerce. Minobe Shunkichi, Councilor at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, was also prevailed upon to hear the appeal.

October 10 (Mon.)

Second campaign. Three committee members, Takano, Sawada and Nagayama, visited the home of Tejima Seiichi in Hongo-Nishikatachô to explain the case to him. Tejima proposed the acceptance, for a certain period, of exceptions to the number of working hours for child labor. Taguchi Ukichi was called on, but he argued for laisser-faire and disagreed that the government should intervene in labor-management relations. Kanai Noburu was called on but he was just about to leave his residence, so the case was briefly outlined to him, and an arrangement was made to call again.

October 14 (Fri.)

Notice was received from the Metropolitan Police Office prohibiting a lantern-lit march headed by a carriage of music band, calling for revision of the Factory Bill. The march, an idea of Sawada Han'nosuke's, had been planned for November 3.

October 15 (Sat.)

Takano Fusatarô spoke at a labor movement meeting in Yokosuka.

October 17 (Mon.)

Countermeasures were discussed at a council meeting of the Ironworkers' Union. It was resolved that:

(1) two large public meetings be held around the time of the opening of the new Diet session.

(2) a pamphlet detailing proposals for revision of the Factory Bill should be printed and copies sent to the members of the Agriculture, Industry and Commerce Higher Council and to the members of the Union.

(3) copies of the pamphlet should be distributed at the conference of the Kenseitô (Constititional Party)

October 21 (Fri.)

Takano and Sawada went to the Ministry of Home Affairs and presented a 'Petition for the Protection of Industrial Workers' to the Minister Ôishi Masami, signed and sealed by the members of Kiseikai and the of the Ironworkers' Union.

October 22 (Sat.)

Three committee members, Takano, Katayama and Sawada called on the residence of Nakano Buei, but he was out. Minoura Katsundo declined a request for a meeting on the grounds that he was about to leave for his office. Suzuki Michimi of the Home Affairs Ministry also declined to meet them, saying he was too busy. They called on the home of Soeda Juichi, but he was out. They then called at the Tokyo Horse-Drawn Railcar Company to see Nakano Buei, but he too was out.

October 23 (Sun.)

Committee members spoke at at a Kiseikai meeting on the the revision of the Factory Bill issue, held at Tsutaza in Yokohama. 1,300 people attended. Takano Fusatarô gave the opening address and in a speech titled "What is needed from Prime Minister Ôkuma" (Ôkuma naikaku sôri daijin ni nozomu) expressed dissatisfaction with the Factory Bill and argued that if it became law, it would invitably contravene the aim of improving protection for workers. He went on to call on the workers to stiffen their resolve against the Bill and to urge the need for a great campaign of opposition to it.

October 24 (Mon.)

The Higher Council of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce began its deliberations on the Factory Bill.

October 28 (Fri.)

Together with provisional committee member Natsume Kumanoshin, Takano Fusatarô visited Hamaoka Sentetsu at the hotel where he was staying, but as Hamaoka was just about to leave the hotel, an appointment was made for another day. Doi Michio was just then seeing visitors at the same hotel so instead, they put their case to Hamada Kenjirô, Chief Secretary at the Osaka Chamber of Commerce, who showed his agreement with the committee members' views.

November 2 (Wed.)

Takano Fusatarô met Shimura Gentarô, former Head of the Office of Industrial Affairs and a member of the Higher Council.

These various activities pursued by Kiseikai achieved results to a certain extent. On November 2, the Higher Council of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce put to a vote a committee proposal for revision of certain articles in the Factory Bill, and of the 28 members, 15 voted in favor of revision, with 13 against; the proposal for revision thus passed. In the proposal, the regulation in the Bill that related to the 'employment certificate' (shokkôshô), the item that Kiseikai had been most concerned about, was deleted.

On November 6, Kiseikai held a public meeting on the subject of the Factory Bill at the Kinkikan Hall in Kanda. Fusatarô spoke of the theme of 'Evaluating the Factory Bill'. He judged that the Kiseikai campaign had had some success in that the Higher Council's revision proposal was superior to the original draft Bill and argued that the existence of labor unions would be significant if this legislation were to become effective.

However, the first Ôkuma Cabinet, which had intiated the Bill, collapsed virtually before the Higher Council vote, and this, in effect, killed the effort to revise the Bill. In the struggle for government posts following the forced resignation of Education Minister Ozaki Yukio after a speech he gave that was accused of 'republicanism', the Minister for Agriculture and Commerce, Ôishi Masami resigned. The Bill was not submitted to the Diet and the incoming government, the second Yamagata Aritomo Cabinet shelved it. Just when the proposals for revision, which reflected the wishes of Kiseikai, had been passed in the Higher Council vote, the Bill could not become law without being presented to the Diet. It might seem as if all the efforts Fusatarô had put into the campaign to revise the Bill had been rendered meaningless. But when one reads the shorthand report of the Higher Council's deliberations, it becomes clear that unions existed in Japan and had the capacity to put their views on labor policy to the capitalists, bureaucrats and academics who made up the Council, and that fact in itself meant that the campaign to revise the Factory Bill was not in vain.

Further, the 'statement of opinions' that the Kiseikai council meeting of October 17 resolved to draw up was published as Statement of Opinion on the Factory Bill (Kôjô hôan ni taisuru ikenshô). Responsibility for editing and publishing the document was stated on the document as being that of Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai, the name of whose representative was recorded as Takano Fusatarô. It was printed by Shûeisha on October 31 and published on December 3. It had already been distributed to all the members of the ministerial Higher Council on November 1, so that prior to its general publication, a pamphlet version seems to have been prepared for the purposes of the appeal.

A funeral procession in straw sandals - the death of Sakuma Tei'ichi

While he was busy on his rounds in the midst of the campaign to secure revision of the Factory Bill, Fusatarô's heart must have been weighed down with the knowledge that the serious illness which Sakuma Tei'ichi was then suffering had become critical. Sakuma had been an eager and influential supporter of Kiseikai, also a member of the Higher Council of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce that was deliberating on the issue of the Factory Bill revision. Sakuma was someone Kiseikai was relying on to help carry through the demand for revision of the Bill. But Sakuma's health, afflicted by lung disease since his youth, suddenly took a serious turn for the worse, to the point where even his attendance at the Higher Council meetings was in danger. Fusatarô felt that he himself was to blame for this decline in Sakuma's health. Sakuma Tei'ichi had responded to Fusatarô's requests by ignoring his illness and by speaking at Kiseikai monthly meetings. And furthermore on October 3, he had disregarded his doctor's advice of not having visitors, invited Fusatarô and other Kiseikai committee members to his sickbed, when he had energetically given them his advice about the Factory Bill. It was after this day that his condition rapidly declined. When they learned of this, the Ironworkers' Union council resolved that a visit be paid to Sakuma's residence to express their care and concern, and on October 19, Fusatarô visited Sakuma's sickroom with a long letter expressing sympathy and good wishes, and a bottle of wine. It is only too clear from the emotional 'letter of sympathy' how much the members of Kiseikai felt that they relied on Sakuma. That the very ill Sakuma should then have taken the pains to write them a letter of thanks in reply deeply moved Fusatarô and his colleagues.

However, on November 6, 1898, four days after the Higher Council voted to revise the Factory Bill, Sakuma Tei'ichi passed away. He was 50 years old. 5,000 mourners attended his funeral, which was held on November 9 at Seizôin temple in Shitaya-kanasugi. Onlookers were astounded to see the many groups of workers in their straw sandals carrying banners as they processed in the column of mourners along with members of the government and other prominent personalities.

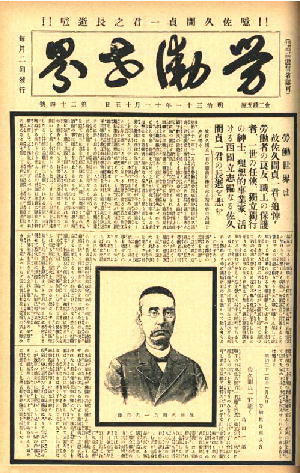

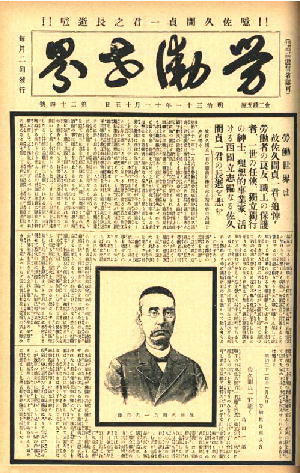

Members of Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union came not only from Tokyo but from Yokohama, Yokosuka and other areas to attend as mourners in the funeral procession. The entire front page of the November 15, 1898 edition of The Labor World was given over to the obituary for Sakuma Tei'ichi, and the first of the memorial addresses offered to the deceased was printed in the name of Rodô Kumiai Kiseikai. No name was attached but it was likely written by Takano Fusatarô. From the very formal manner of the phrasing of the memorial address, it seems likely he got someone to help him in the writing of it. To present the whole text here would certainly be to give a good idea of Fusatarô's feelings for Sakuma, but the text is long and has had to be omitted.

Kaneko Kentarô's great speech in support of Kiseikai

The 'Sakuma Tei'ichi obituary issue' of The Labor World included various items related to Sakuma's passing, but also announced that former Minister of Agriculture and Commerce Kaneko Kentarô would deliver an 'academic lecture' titled "The Prospects for Industrial Workers" to Kiseikai members on November 20. Kaneko was known to favor the passing of Factory Act legislation and as a bureaucrat who understood labor issues. Kiseikai had great hopes of him. The level of that expectation was shown in the fact that when in April 1898 Kaneko had been appointed Minister of Agriculture and Commerce in the third Ito Hirobumi Cabinet, The Labor World had printed an editorial titled 'Welcoming New Minister Kaneko' on the front page in which it welcomed Kaneko's appointment.

However, after only two months in office, Minister Kaneko had to vacate his position due to a change of government. Nevertheless, it amounted to something that a man who had served as assistant secretary at the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, within whose purlieu labor issues fell, a man who furthermore had then gone on to become Minister, would accept a request to give a lecture at a Kiseikai meeting. This was a momentous event.

On the day, some 700-800 people gathered at the YMCA Hall in Kanda to hear him. This was no small number, but 1200 had been present at the founding of the Ironworkers' Union, and the ordinary Kiseikai members evidently had not had as much interest in the upcoming lecture by Kaneko as Fusatarô had hoped. Nevertheless, the audience were most impressed by Kaneko's speech and responded with thunderous applause.

The content of the 90 minute lecture was taken down in shorthand and later published in The Labor World. There is not space here to reproduce all of it, but an extract will be presented. At the outset, Kaneko explained how his lecture would be structured in five parts: (1) the status of industrial workers (2) workers' sense of thriftiness (3) worker's groups (4) workers' leaders (5) workers in the aftermath of the foreign residents' issue. In the first part, about workers' status, he argued as follows:

Industrial workers provide the motive force behind the modern civilization and enlightenment of the nation. During the Sino-Japanese War the Railways Office had to deal with tremendous transportation issues. Everyone and everything had to be transported by rail to Yokohama, from where they were shipped abroad. The railways were all built and maintained by workers. The trains can only run because of the workers. Therefore, workers are the power of modern industry. Japan Railways introduced its reforms because they were told that that if the workers go on strike, the trains will not run! (loud applause)

I want you workers please to hold your heads high, each one of you feeling himself to be 'Mr Worker' (loud applause). If someone despises his own status, then that status will certainly be despised by others. If you think of yourself as 'Mr Worker', people will say with respect "he's a carpenter", "he's a blacksmith", and you will not be looked down upon (shouts of agreement from the audience). In life those who are most to be despised are those who live by leeching off others - these are the worst types. Industrial workers have all learned their own skills. I do not think there are any more noble human beings than this. Workers! Do not look down on your own status, but rather, think: "I am a motive force in the nation's economy and society. Because I am here, the country grows wealthy! It is with the money that I make that the army and navy can be maintained. It is on my money that the nation's economy stands." If you go on with these proud thoughts, you will all be respected by everyone. Then your character will become refined and you will be able to attain to the status of workers in a truly modern nation, with no reason for any shame. This is what I hope for! (loud applause)

As we have already seen, industrial workers at that time were liable to feel great dissatisfaction about the way in which their status was regarded as that of 'the lower classes'. Kaneko well understood the workers' feelings on this score and strongly emphasized the fact that their energies were upholding the country's economy, urging them that it was important to realize that if they respected themselves, then everyone else would respect them. Kaneko, who was known as an excellent orator, had the ability to reach the hearts of his audience; this much is clear. For a former Minister to say approvingly in a public speech that the Japan Railways strike had led to reforms in the railways was a bold statement indeed.

Kaneko went on to address the question of what he indicated to be the weak point of Japanese workers - their lack of thrift, as exemplified in the Japanese saying 'money is not something to be kept overnight' and called for improvement in this area. Then he turned to his third topic, 'workers' groups', in other words, unions.

When workers are all scattered about in little bunches, their power is weak. Politicians pay no attention at all to workers, and capitalists have little fear of them. People neither recognize workers nor see the part they play in the country's economy. But when workers combine together in groups of 100, 2,000 or 10,000 then the fact is that they become really strong.....Japan is really a fine country; there is not a single law that bans workers' groups....making workers' groups strong means making the foundations of the nation's industry strong. It is not something only for the workers' sake; it is for the sake of the nation (loud applause). Countries where workers' groups are weak are after all, weak countries (applause). For a country where workers' groups are strong, look at England. Of all the countries in the world there is no industrial nation as solidly built as England. (applause) Therefore, you who have established this Rôdô Kumiai Kiseikai, starting out from Tokyo, gradually form workers' unions in Ôsaka, Kyôto, Nagoya and all the other other regions until there is a national network of unions with its headquarters in Tokyo, and if you can direct all of Japan's workers from Tokyo, Japan's industry will become stronger than it is now, it will progress more than it does now and the nation of Japan will become more prosperous and wealthy than it is now (thunderous applause)

All the points of Kaneko's argument in this passage matched Fusatarô's own thinking exactly. He must have thought: "Kaneko has read my mind". What would have especially gladdened him was that Kaneko boldly said: "There is not a single law in Japan banning workers' groups. I want to see workers forming groups to make a solid contribution to the wealth of the nation; this has been the goal of the government's policy since the Meiji Restoration." That Kaneko, who had been involved in the enactment of the Imperial Constitution law, a man who had lectured on administrative law at the Imperial University and was known as a distinguished legal expert, should have made such a declarative statement must have made Fusatarô and his colleagues feel that their movement had been given a real seal of approval.

In the fourth part of his speech, 'Workers' Leaders', Kaneko pointed out that if workers were to establish their own groups, those groups must be under control of leaders able represent the views of the unions to society and to politicians. Moreover, representatives of the unions needed to be sent to the Diet. This last call was meaningful insofar as it showed Kiseikai a long-term goal, but under the prevailing limited election system it was a proposal rather lacking in realism. Talk of sending workers' leaders to the House of Peers and such like was fanciful talk indeed. Nevertheless, Kaneko's point that the Ministry's Higher Council vote to revise the Factory Bill was not sufficient cause for rejoicing struck a chord with Fusatarô. Kaneko's speech as a whole was in harmony with Fusatarô's own thinking, and since his own views were now being expressed by a high-ranking bureaucrat who had had charge of the Ministry tasked with oversight of labor affairs, Fusatarô must have felt, as the Japanese saying has it, that he had 'gained a million allies'.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), The latter half of the Chapter 10 Tekkokumiai no tanjo

|