Chapter 10 The Birth of the Ironworkers' Union

|

| Branch No | Workplace (org. base) | No. of members |

|---|---|---|

| No. 1 | Tokyo Arsenal small arms finishing workshop | 189 |

| No. 2 | Japan Railways Oomiya Yard | 53 |

| No. 3 | Yokohama Shipyards | 185 |

| No. 4 | Ministry of Posts and Telegraphy Lightouse Equipment workshop | 49 |

| No. 5 | Tokyo Arsenal small arms manufacturing workshop | 163 |

| No. 6 | Factories in the Honjo area | 136 |

| No. 7 | Tokyo Arsenal small arms repair workshop | 108 |

| No. 8 | Tokyo Arsenal small arms assembly workshop | 69 |

| No. 9 | Tokyo Arsenal small arms casting workshop | 41 |

| No.10 | Tokyo Arsenal rifle casting workshop | 64 |

| No.11 | Tokyo Arsenal rifle equipment casting workshop | 43 |

| No.12 | Shimbashi Railyard foundry | 51 |

| No.13 | Shimbashi Railyard turning workshop | 35 |

Further, there were six members who were railway workers at Kôbu Railways, the forerunner of today's Japan Railways, although it is unclear to which branch they belonged.

The most noteworthy feature of the above table is the the huge proportion of the Tokyo Arsenal workers. With seven branches and 677 members, they accounted for half the total number of both branches and members. We have already discussed the Arsenal itself. It was located on the site of the former Mito clan's official residence at Edo. Surrounded by a high fence and brick-built walls, it was a huge area extending over 330,000㎡ from today's Tokyo Dome and Koishikawa Kôrakuen in Suidobashi to Kasugachô and part of the Chuô University Kôrakuen campus.

The union's No.2 Branch, located at Japan Railways' Ômiya Yard, was the factory that produced the main rolling stock for Japan Railways. Despite pressure from the management, the branch grew to become the strongest in the union.

No. 3 Branch and No.6 Branch were both outside of Tokyo. The Yokohama branch organized metalworkers who worked on ship repairs. Whereas other branches were based at single workplaces, these two branches organized workers employed at various locations. Details for No.3 Branch are unknown, but the names of the workplaces where No. 6 Branch members were employed and their numbers are as follows: 43 worked at the Hiraoka factory in Kinshichô, Honjo ward, known for its manufacture of railway carriages; 53 worked at the Nagashima Works in Sotodechô, Honjo ward, which produced machine tooks; 14 were employed at the Takeuchi Safe Company in Minami-Futabachô, Honjo ward, making safes and strong boxes; 15 were employees at the Tokyo Spinning Works at Higashidaikuchô, Fukagawa ward, and 11 worked at the Hara Ironworks. All year-round, unpaid service

The union had its five council members but only one, Takano Fusatarô, was engaged in daily work for the union. Katayama was the head of the Kingsley Hall and also editor-in-chief of The Labor World, and the other union council members were all workers, who could not just take time off when they felt like it. Even the accounts manager was only able to be at the union head office once a month.

But Fusatarô was not only an Ironworkers' Union council member; he also had his responsibilities as chief secretary of Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai. The great majority of Kiseikai members, however, were ironworkers, so the two posts were inseparable. The campaign activities of the Ironworkers' Union were also those of Kiseikai. Moreover, the head office of both organizations was in the same rented rooms at the Yanagiya inn, so Fusatarô's daily commute from his mother's house in Hongo to Gofukuchô remained exactly the same.

It was nevertheless the case that with the foundation of the Ironworkers' Union, Fusatarô's workload rapidly grew. The number of meetings of various kinds more than doubled. There was a stream of visits to the office by Kiseikai members and Ironworkers' Union branch officials asking for advice. To cope with this situation Fusatarô had his office hours printed in The Labor World. These were only in the afternoons, but every afternoon, seven days a week, all year round:

Sun. Mon. Tues. Wed. Thurs. 1.30 pm - 6.30 pm

Fri. Sat. 1.00 pm - 5.00 pm

Jan. 10

Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai Office

His appearances as a speaker at public meetings increased considerably; besides Tokyo and Yokohama, locations extended to Yokosuka, the location of the Navy Arsenal, and the prefectures of the Tôhoku region, where Japan Railways had its rolling stock factories. Unfortunately, there are no entries in Fusatarô's diary for 1897, so we cannot compare his workload for that year with other years, but it is nevertheless clear that he was extremely busy, as the first sentences of his letters to Gompers at this time invariably attest. For example, the letter of August 23 1898 begins

Dear Sir,

Please pardon my negligence of not writing you for so long a time. Since the formation of Iron Workers Union I was & am besieged with great volumes of work so that my time is wholly taken by them.

Such was the situation, and it was impossible for Fusatarô alone to handle all the affairs of both Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union, so a secretary was employed to help him, who likely dealt with the office work relating to finance. From the founding of the Ironworkers' Union, all the office costs of the two organizations, including the secretary's salary, were split evenly between the two bodies.

Activists under surveillance

In addition to all his busy duties, Fusataroo had other worries at this time. One was his livelihood. He was not paid for his services to Kiseikai and the Union, but although he was so busy, he still had to earn a living. His expenditure had also increased. We shall return to this topic later.

The second problem was more unpleasant. From around the time of the founding of Kiseikai, the police had begin to identify him as "a subject requiring surveillance" - someone to keep an eye on (yô chui jinbutsu). To begin with, this simply meant a policeman in civilian clothes attended public meetings, but gradually, the degree of surveillance was stepped up to the point where the movement was beginning to come under continuous obstruction. The main activists were regularly tailed by uniformed officers, while detectives visited their homes to check their identity. Eventually, large numbers of uniformed officers were sent to public meetings, intimidating the audiences and quietly pressuring the hall owners to stop letting out their premises for public meetings to Kiseikai and the Union. Activists were then required to submit to the authorities lists of participants at the meetings.

These activities by the police were not at all reported, either by The Labor World nor in other Japanese newspapers and magazines at that time. It was probably felt at The Labor World that it would prevent union members becoming anxious about the movement and also avoid more suspicion and hostility from the side of the police. In his reports to America, where such concerns were not a problem, Fusatarô described concretely the repressive measures taken by the authorities in Japan. A report of his, written on January 17, 1898, soon after the founding of the union and published in the AFL newpaper, included the following:

It was in the evening of June 25, 1897, when a public meeting was held with the sole purpose of essaying that grand cause of labor and took the ever sensitive police authorities of this capital city with surprise. Habituated as the police authorities were to slight workingmen, they never dreamed that workers of this country are capable of inaugurating and carrying on any systematic effort as represented by the labor movement. Nor did they ever suppose that the cause of labor is able to command hearty support of such well-known public men as Messrs. Saburo Shimada, vice-president of the Lower House of the Diet, and Teiichi Sakuma, the well-known capitalist.

Amid their innocent slumbering, as it were, there suddenly came the public announcement of a mass meeting with many well-known public men as the speakers of the evening. Truly, it was a complete surprise to those who took the meeting as the first sign of approaching violence on the part of the working people. Uncalled-for gravity was thus given to the meeting, and unnecessary precautions were taken by them. Scores of secret service men were dispatched to the meeting room. But, contrary to their expectations, there never assembled such an orderly crowd of working people as the audience of that meeting.

Furthermore, no inflammatory remarks were uttered by the speakers. Far from that, every speaker counseled the audience as well as workingmen in general to restrain from any violent action but go ahead with the formation of trade unions. And, strange to the police, these moderate counselings met with an enthusiastic reception from the audience. Disappointed and puzzled as they were, they were not yet ready to give up their suspicion and straightway they instituted a close watch on those who were instrumental in bringing the meeting into consummation. Private residences of the leaders were made objects of frequent calls of detectives. Their past records were secretly investigated. Their daily movements were closely followed as if they were suspected criminals. The peaceful home life of the leaders was ruthlessly disturbed and their woeful tales thus commenced. However, the authorities have again failed to find in this direction any pretext to crush the movement. Their next move was toward obstructive tactics for the successful consummation of meetings and covert threats against those who joined the movement.

At one time, uniformed police were stationed in our meeting, under the cover of preserving order in the meeting room, but in reality, to overawe attending workingmen, and at the same time to watch the utterances of speakers. At another time they covertly forbade the renting of a hall for our meeting. On another occasion they demanded all the names of those who joined the movement, which was meant to scare the enrolled members away from the movement.

Despite all these, no disturbing elements of public peace were discovered in our movement, and their only reward was making the lives of the leaders more miserable.

From the tightening of police surveillance and its obstructive behavior, Fusatarô had a clear premonition of the difficulties the movement would face in the years ahead.

A substantial year

January 1898 saw Fusatarô's 29th birthday. This year, which brought his twenties to a close, was the most substantial year of his whole life, both in the personal and the public sense. The most important event in his private life in that year was his marriage, but we shall return to that later.

At the end of the previous year, following on from the Japanese-English Dictionary (Wa-Ei Jiten), which he had compiled with his brother and others, on January 6 English-Japanese Business Conversation (Ei-wa shôgyô kaiwa), which he had written by himself, was published by ÔKura Shoten. The book was laid out in a new, conversational format. The style is normal in English conversation textbooks in Japan today, but it was Fusatarô who came up with the idea for it. He writes about the process in his diary:

Moreover, and this also relates to his public activity, Fusatarô was sending regular monthly 'reports from Japan' to American labor newspapers, which supported his livelihood. All his reports have been reproduced on this website as Takano Papers.

On the organizational front, he continued to put his energies into expanding the activities of Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union, and with great results. Throughout the year, he gave speeches at public meetings in Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka and in various places in the Keihin area, and in the summer went on a speaking tour in the Tôhoku region of northern Japan. In the autumn he took an energetic part in the campaign to revise the Factory Bill and at the end of the year founded the Ironworkers' Consumer Cooperatives. He focused on the cooperative movement and continued to play an energetic role in it.

At this point, of all of Fusatarô's various activities, let us concentrate on the one into which he put his greatest efforts - the development of the Ironworkers' Union. The union, which at the time of its founding at the end of 1897 had 1,183 members, continued to make very steady progress in its expansion throughout 1898. New branches were added every month, and about halfway through the year, there were 2,500 members, more than twice the number at the union's founding. By the end of 1898 the union had grown to the number of 32 branches and 2,717 members. This was not a time like that after World War II, when all workers at one workplace would belong to one universal workplace union and union dues were docked from workers' wages. In 1898 workers had to be persuaded individually to join the union; members paid their entrance fee individually, and the union had to collect its dues every month from each individual member. The names of the new branches founded in the year 1898 and the names of the companies where the new branches were based are shown below:

| Branch No | Workplace (org. base) | Date of founding |

|---|---|---|

| No.14 | Shibaura Works | Feb. 11 |

| No.15 | Shimbashi Railways Works Finishing Yard | Feb. 11 |

| No.16 | Ishikawajima Shipyard wrought iron section | March 1 |

| No.17 | Yokosuka Navy Arsenal | March 3 |

| No.18 | Kôbu Railroad Company Works | 1March 13 |

| No.19 | Tokyo Arsenal Rifle Parts Workshop | 1March 20 |

| No.20 | Ishikawajima Shipyard | April 24 |

| No.21 | Ishikawajima Shipyard Wrought iron section | May 1 |

| No.22 | Akabane Navy Arsenal | May 10 |

| No.23 | Japan Railways Fukushima, Kuroiso, Sendai | May 25 |

| No.24 | Tokyo Bay Steamship Company | July 9 |

| No.25 | Japan Railways Aomori Works | Aug. 5 |

| No.26 | Japan Railways Morioka Works | Aug. 6 |

| No.27 | Tokyo Arsenal Rifle Parts Workshop | Aug. 13 |

| No.28 | Tokyo Arsenal small arms turning workshop | October |

| No.29 | Hokkaidô Public Railroad Works (Takigawa) | October |

| No.30 | Tokyo Arsenal Rifle stock workshop | October |

| No.31 | Ishikawajima Shipyard Rolling Stock Works | October |

| No.32 | Ishikawajima Shipyard (Finishing Yard) | October |

We have already seen the branches that existed at the time of the union's founding in December 1897. Comparison of the two tables, December 1897 and 1898 shows clearly that the 13 branches at the end of 1897 had been augmented by a further 19 branches, making a total of 32 braches by the end of 1898. As usual, the Tokyo Arsenal was the main base for the new branches; there were 10 there in December 1898. The Arsenal branches shared a common office at the Jôhoku region joint branch at Kanda-Misakichô, from where they not only gathered union dues but provided a job-hunting service for ironworkers, set up a cooperative shop, collected contributions and donations for branch members who had suffered in disasters of one kind or other and functioned energetically as a body facilitating cohesion among the branches at the Arsenal.

Another conspicuous achievement was the successful unionization of the 4,000 employees at the Yokosuka Navy Arsenal, second only to the Army Arsenal in the Kanto region in the scale of its metal-workshops. At the time of the union's founding, the level of unionization, at only about 250, had not been so great. Also, at Japan's first privately-owned, western-style factory, Ishikawajima Shipyard, five new branches were established. Over 600 men were employed at Ishikawajima Shipyard, so the scale was smaller than at the two arsenals, but the level of unionization was higher. Other successes were at the Shibaura Works, the Shimbashi Railways Works, the Japan Railways Works and the main engineering works in eastern Japan.

Labor is Sacred ? the reasons for ironworkers' participation

Why then was it ironworkers and among them, Tokyo Arsenal workers, who responded in such overwhelming numbers to the call from Fusatarô and his comrades? The question is difficult and not really a suitable one to be addressed in a biography. It is not enough only to explain why ironworkers joined the movement; one has to be able to answer the question as to why other workers did not choose to join if one is to produce a serious research paper. To come to a real evaluation of Takano Fusatarô's achievements, however, these are questions that cannot be bypassed. We shall commence with the first one.

It used to be the case that in seeking the reasons for the emergence of labor unions, labor historians tended to ascribe them to economic deprivation. They would emphasize workers' poor working conditions as the causal factor and that in order to ameliorate such bad conditions, workers banded together in unions. However, this view stemmed from a certain fixed idea that labor unions were organizations for workers to sell their labor, and when one looks at the actual growth process of individual unions, one finds that this concept does not apply in numerous cases. Nor does this interpretation fit the case of the Ironworkers' Union. In fact, those who took the initiative in Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union, those who participated actively and became the key campaigners were men who were earning high wages compared to most other workers.

For example, Muramatsu Tamitarô, who visited Fusatarô right after the founding meeting of Kiseikai and who became its secretary, was a foreman at the Tokyo Arsenal on a daily wage of more than 1 yen a day. Mamie Kintarô and Matsuda Ichitarô, who became Kiseikai standing committee members, frequently contributed 30 sen or 1 yen - no mean sum in those days - towards the expenses for public meetings. Hirai Umegorô, appointed the union's first general manager, was a foreman (shokuchô) at the Yokohama Dock and contributed 3 yen towards the costs of the opening ceremony. Morita Chôkichi, who followed Hirai as general manager, was a foreman at the No. 161 Iron Workshop in Yokohama and was "a powerful man with many workers under him who was treated by his comrades as a gang boss (oyabun). Ozawa Benzô, the union's welfare manager who was also elected chairman of the council, the union's representative body, was a highly paid man who paid direct national taxes of over 15 yen a year. In short, the union's leading activists and officials were very well-paid workers.

So why did such relatively highly paid 'senior workers' participate so actively in Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union? The main reason was their 'anger at discrimination against workers'. Their workplaces had started operating around the end of the feudal period (the 1860s - 70s) and were at that time unfamiliar to Japanese. Factory work was an occupation people were forced to take when they had no other means of supporting themselves and it had very low social status in comparison with traditional artisans' occupations such as carpentry or plastering. 'Factory laborers' (shokkô) were thus looked down on as being one level lower than everyone else in society. One can sense their feeling of inferiority from the fact that they never referred to themselves by the term shokkô (factory laborers) that others used for them but always as shokunin (artisan, craftsman).

Not only were they looked down on by the rest of society, they were also discriminated against in their workplaces. They were not recognized as 'regular employees' and were treated as 'manpower', a resource like natural materials. For example, the '11th Annual Statistical Report of the Ministry of the Army', which collated statistics for 1897, recorded the Tokyo Arsenal 'employees' (shokuin) as military personnel 65 persons and army auxiliaries 193 individuals, yet the workers who toiled there were recorded total of 1,601,855 man-days over the course of the year. The same treatment can be seen in the History of the Yokosuka Navy Yard (Yokosuka kaigun senshôshi). This was not just a matter of the technical ways in which statistics were recorded; it reflected the state of human relations at the workplace.

Those who had direct supervision of workers at military arsenals were the workshop chiefs who had the status of technicians. An arsenal would consist of 50-60 separate workshops, each of which would have its own workshop chief. These men were chosen from the graduates of arsenal technical schools that had been set up alongside the army arsenals. These arsenal schools were run on a three-year program and according to regulations, were supposedly open to anyone who had graduated from elementary school (shôgakkô) but in fact, only serving soldiers were accepted. Workers bitterly resented the fact that whereas they had the same level of elementary school education as the workshop chiefs, the status of the latter was higher simply because they had been to an arsenal technical school.

Yokoyama Gen'nosuke describes the relations between the two groups as follows:

Relations between the workshop chiefs and the laborers (shokkô) were always difficult. The chiefs received their instructions from supervisors and were charged with overseeing directly the work of the laborers and they were obviously supposed to be skilled in technical matters, but in fact, those who had only recently graduated from the arsenal technical school were proud of the little they had learned at school and tried to use their authority as overseers to put pressure on the laborers, and this roused the laborers' indignation. Although the two groups should have tried to get along with each other, in every workshop, while laborers would seem on the surface to be obeying orders, in fact, relations between them were like those between dogs and wolves - really bad....it is unreasonable to expect that there would be no clashes between soldiers, who had normally only been to elementary school and who, after only three years of a special education, could be so haughty in their treatment of the workers under them, and those workers, who were so proud of the skills they had acquired in over 15-20 years of near sacred service. The workers would gossip darkly among themselves, saying things about the workshop chiefs like "You think anyone's going to say 'yes sir, no sir' after listening to some young fellow just out of the army making out like he knows everything and ordering everyone around?" In extreme cases one of them would even be chosen to help the workshop chief run the workshop as an assistant, or they would laugh at the chief's unreasonable behavior behind his back. [Sensô to rôdô shakai (War and the labor society].

Technicians (gite) had military status but were low-level overseers and at the arsenal belonged to the lowest-ranking army officers. As soldiers, they were accustomed to being constantly ordered about and turned their resentment at this towards the workers under them. Yokoyama has the following to say about the supervisors (joyaku) who were also in positions over the workers.

To supervise the workers, foremen were chosen from among those workers who had worked for many years. However, this was no more than a job helping out the workshop chiefs. They had no power over the workers. All authority to direct and supervise the workers was in the hands of the workshop chiefs.

In other words, the 'supervisers had no authority at all; they were no more than assistants to the workshop chiefs. This was not unrelated to why a man like Muramatsu Tamitarô took the initiative to join Kiseikai and the Ironworkers' Union.

Industrial workers also greatly resented the degree to which they were managed in accordance with so many rules and regulations. The workplaces where union members were employed were all large enterprises such as the arsenals, and as they were so large, rules were obviously needed to manage so many employees. These rules were enforced by means of fines, penalties and dismissals, and behind the power of the workshop chiefs in charge of the workers at the arsenals were these punitive regulations. How far these regulations were actually applied is not known, but their oppressive character is clearly discernible from figures in the 'Annual Statistical Report of the Ministry of the Army (Rikugunshô tôkei nenpô). In the 'operational income' columns for the year 1897 'fines and forfeitures' accounted for 3,111 yen and 35 sen, and penalties for as much as 17,673 yen.

One clear sign of the workplace discrimination that workers were subject to was in their lunchboxes. The arsenals did not allow men to bring their own lunchboxes to work; all employees were forced to buy their lunches from commissioned suppliers. The discrimination that this entailed between workers and their supervisers was one cause of their rancor. The fiftieth issue of The Labor World carried an article titled "The Arsenal is tuberculosis factory":

There are three kinds of lunchboxes in the Tokyo arsenal, A, B, and C. The A type cost 12 sen and are available only to officials; they are out of bounds for workers. The B type cost 6 sen and the C type 3 sen. Workers eat the C type lunch. In fact, the C lunch for the officials and the C lunch for the workers are made up differently. Officials get the better quality ingredients while workers are given lower grade; rice with some husks etc... Lunchboxes for the 10,000 workers are made up at the arsnal and most of them consist of little more than cold rice. Thus, these miserable, dirty lunchboxes spread tuberculosis and other diseases. With the compulsion and pressure they are under, workers have no option but to buy the wretched contents of these unhygienic lunchboxes. They are not allowed to bring in their own lunchboxes.

The situation was the same in privately owned companies, as was attested by Masumoto Uhei, a technician at the Mitsubishi shipyard in Nagasaki, a delegate at the first conference of the International Labor Organization (ILO).

No-one would want the life of an industrial worker (shokkô). In the eyes of society at large, industrial workers are less than normal people and are thought of like cows or horses. Although they think they can do nothing about their own situation, even if they themselves drop to the level of beggars, they don't want their children to become factory workers. This feeling has predominated in Japan in recent years.Take the Mitsubishi Shipyard at Nagasaki, for example, with its affiliated school supposed to be for educating workers. The feeling among the workforce there about educating workers was that one generation of the family in factory work was quite enough thank you very much, and that there were no parents in the world who were stupid enough to send their children to school in order to become factory workers. This is how people felt in the shipyard about schools to train workers in the time before the Russo-Japanese War. (Rôshi kaihôron [Workers' Liberation])

This anger against discrimination was felt less by those workers who had just been hired; rather, it had built up among those of long experience at work and who were relatively well-paid, so-called 'senior workers'. It was only natural that they should have thought of aiming to break out of their present situation and seek to improve workers' social status.

Especially among workers at the arsenals, there were those who had been conscripted to fight in the Sino-Japanese War, who now earned a good wage, were regarded highly as key workers on account of their war record and had even won decorations for their war service. Muramatsu Tamitarô seems to have been one of them. To have been through such experiences of war and then to return again to experience discrimination at work and in society must have been intolerable. The words "labor is sacred" which rang out in A Call to All Workers (Shokkô shokun ni yosu) struck a deep chord with these men. "Workers are human beings too. Without their labor, this society would not be what it is. Let them respect themselves and join in solidarity!" This call had spoken to them and resolved them to join the union.

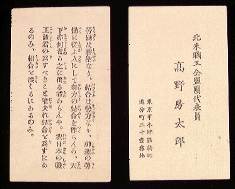

On the back of his namecard Fusatarô had the following words printed :

On the back of his namecard Fusatarô had the following words printed :

Labor is sacred, union is strength. You who are engaged in such sacred labor, will you not combine together? Is there anyone in society to whom this does not apply? Workers of Japan need do only this - join together and form unions!

|

This file was last modified on: November 18, 2014. |

Top page in English |

prev.:9. Personalities in the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions - a group to promote the labor movement next: 11. Why artisans' unions did not join Kiseikai - Qualifications in the West, experience in Japan - |

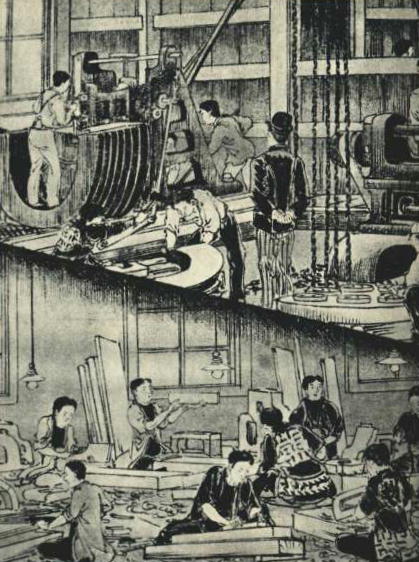

![The 27 founding committee members. Front row, left: Takano Fusataro and next to him, Katayama Sen (from Katayama Sen and Nishikawa Mitsujiro, Nihon no rodo undo [The Labour Movement in Japan]](../jpegfiles/tekkokumiai.jpg)

There were flowers and bonsai placed throughout the YMCA building itself, and the participants were greeted with some energetic playing by a group of musicians. It is clear from the extent of the preparations, which included such decorations and even music, how confident the union members felt in themselves and how much they had looked forward to this day. Over 1,180 members of the Ironworkers' Union were present as well as members of Kiseikai, and of various other occupations, making a total of 1,300 participants. The Mainichi Newspaper the following day carried this report:

There were flowers and bonsai placed throughout the YMCA building itself, and the participants were greeted with some energetic playing by a group of musicians. It is clear from the extent of the preparations, which included such decorations and even music, how confident the union members felt in themselves and how much they had looked forward to this day. Over 1,180 members of the Ironworkers' Union were present as well as members of Kiseikai, and of various other occupations, making a total of 1,300 participants. The Mainichi Newspaper the following day carried this report:![The front page of the first issue of the Rôdô Kiseikai newspaper Rôdô Sekai [(The) Labor World],](../jpegfiles/laborworld.jpg)