9. Personalities in the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions

- A group to promote the labor movement -

The founding meeting

From the day after the successful public meeting at the YMCA Hall, Takano Fusatarô embarked on the preparations for the founding meeting of the Rôdô-kumiai Kiseikai (Society for the Formation of Labor Unions). On July 5, just ten days after the public meeting, he and his comrades proceeded to hold the founding meeting. The evening on that day, 71 people attended the meeting at a rental room of the 'Ike no O' in Kitamakichô, Kyôbashi Ward, Tokyo, near the present Yaesu exit of Tokyo station. After a speech by Suzuki Jun'ichirô, the by-laws and regulations of the Society were discussed and resolved and in accordance with the by-laws, the meeting went on to elect officials. The three provisional secretaries chosen were the trio of the Friends of Labor: Takano Fusatarô, Jô Tsunetarô, and Sawada Han'nosuke. Fusatarô's long-cherished dream was finally moving towards realization.

Incidentally, there is a tendency to look upon the Rôdô-kumiai Kiseikai as the first Japanese labor union, for example the Wikipedia Japan depicts so in the item of "Rôdô-kumiai (labor union)". However, it certainly was not, the new Society was a promotional group that looked to encourage and campaign for the formation of labor unions. Many of the members were workers, but the Society also included intellectuals.

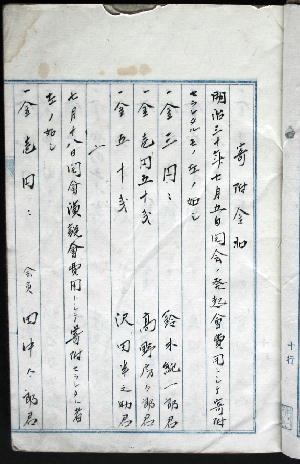

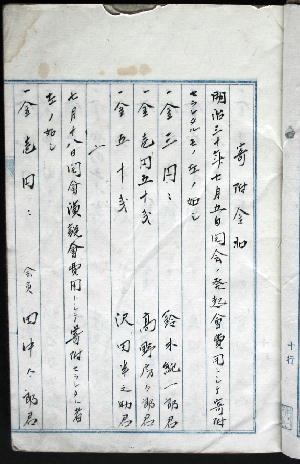

The date of the founding meeting has sometimes been given as July 3 or July 4, but that is also a mistake. Fusatarô's diary records in the column for July 5 that '70 people attended the founding meeting of the Rôdô-kumiai Kiseikai tonight', besides the Rôdô Kiseikai Kifubo (Contributions Book of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions) clearly records 'costs of the founding meeting on July 5'. So, the date of July 5 is definite.

The date of the founding meeting has sometimes been given as July 3 or July 4, but that is also a mistake. Fusatarô's diary records in the column for July 5 that '70 people attended the founding meeting of the Rôdô-kumiai Kiseikai tonight', besides the Rôdô Kiseikai Kifubo (Contributions Book of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions) clearly records 'costs of the founding meeting on July 5'. So, the date of July 5 is definite.

Retracing their steps a little more in detail, let us review the process of preparations from the public meeting on June 25 to the founding meeting of the Society on July 5.

Fusatarô's diary records it as follows:

June 26 (Sat.)

This morning, called on Sawada. From there, visited Mr. Suzuki and discussed the founding meeting of the Society. Left for Yokohama at 7 p.m. by train.

June 30 (Wed.)

This morning 10 a.m. called on Mr. Katayama and Mr. Sawada. At 1 p.m. we all went to call on Mr. Suzuki and decided to hold the founding meeting at Ike no O on the 5th and dined together at Kyûyûtei Restaurant. Returned home at 9 p.m.

July 3 (Sat.)

Sent notices to Society members. Called on Mr. Sawada.

July 5 (Mon.)

This afternoon Mr. Nunokawa Magoichi called. After a pleasant chat about various things he left. Later, called at Mr. Sawada's home. At 5 p.m. we went together to a steak restaurant for dinner and then on to Ike no O. 70 people attended the founding meeting of the Rôdô-kumiai Kiseikai tonight.

A problem here is that the name of Jô Tsunetarô does not appear. From the public meeting of June 25 Jô had worked actively together with Takano, so why did his name not appear until the final stages of Kiseikai? Jô was chosen as one of the provisional secretaries, so he cannot have withdrawn from the movement. Whatever may have been the case, from the time of the public meeting of June 25, Jô's name occurs less and less in Fusatarô's diary. One reason was that after the foundation of the Kiseikai, the office of the Friends of Labor moved to Sawada Han'nosuke's shop. Previously, the phrase "called on Mr. Jô"

occurred frequently in the diary, because the office of the Friends of Labor had been at Jô Tsunetarô's house.

The workers in the membership of Kiseikai

With the founding of the Kiseikai, Fusatarô's circle of acquaintances suddenly grew much wider. Before that, the names recorded in the Takano diary had been limited to those of his comrades in the Friends of Labor such as Jô and Sawada, his 'nightlife companions' such as Ôsawa Ryûkichi, intellectuals from the Social Policy Association and his old friends in Yokohama. These were complemented by a new group of names, mostly those of people with some connection to Kiseikai. For example, in the three weeks between the founding meeting of Kiseikai on July 5 and the first monthly meeting on August 1, the following names of individuals and groups appear:

July 7 (Wed.) Called on Suzuki, Sawada, Ishizu Magoichi.

July 8 (Thurs.) Called on the YMCA, the Bookbinders' Union, Nakazawa Haruyuki.

July 9 (Fri.) Called on Sakuma, Suzuki, Katayama, Sawada, Ishizu, Koide Kichinosuke.

July 11 (Sun.) Called on Suzuki, Sawada.

July 12 (Mon.) Called at the office of the Bookbinders' Union, and on Shimada Saburo and Jô.

July 13 (Tues.) Called on Suzuki, Sawada, and Shûeisha.

July 14 (Wed.) Called on Sawada, Tanaka Tarô, attended a meeting of the Kyokutôshinboku-kai [Far Eastern Friendship Society] at Sanrokutei Restaurant.

July 15 (Thurs.) Called on Sawada, Shûeisha, Ishizu, Koide.

July 16 (Fri.) Called on Sawada, Murayama Tomoyuki. Mamie Kintarô called.

July 17 (Sat.) Yamada Kikuzô and Katayama called.

July 18 (Sun.) Called on Sawada.

July 19 (Mon.) Called on Sawada.

July 21 (Wed.) Called on Sawada, Suzuki.

July 22 (Thurs.) Muramatsu Tamitarô and seven others called.

July 23 (Fri.) Called on Shûeisha, Kakegawa Motoaki, Sawada, Katayama.

July 24 (Sat.) Called on Muramatsu.

July 25 (Sun.) Called on Katayama, Sawada.

July 26 (Mon.) Called on Sawada, Filing manufacturers' Association, met Katayama at Shussen Restaurant.

July 31 (Sat.) Called on Suzuki - not at home. Called on Sawada.

On August 1, 1897. at the Kiseikai's "first monthly meeting", it's officials - secretaries and the standing committee - were selected, the Rôdô-kumiai Kiseikai got underway. Its statutes had already been drawn up at the founding meeting, and in accordance with them, on this day Fusatarô and his comrades nominated the candidates and made the final selection. Chosen as secretaries and standing committee members were the following 15 individuals, with Fusatarô appointed as 'secretary general' by a selection made among the secretaries (Kiseikai had no 'president; so, the 'secretary general' was its chief representative official. The post was unpaid):

∗ Secretaries:

Takano Fusatarô, Katayama Sen, Sawada Han'nosuke, Muramatsu Tamitarô, Yamada Kikuzô

∗ Standing committee members:

Tanaka Tarô, Nomura Shû, Koide Kichinosuke, Matsuoka Otokichi, Shima Shukusaburô, Ishizu Magoichi, Umakai Chônosuke, Mamie Kintarô, Matsuda Ichitarô, Iwata Sukejirô.

If one compares this list of names with those encountered in Fusatarô's diary up to this point, it is evident that most were individuals with whom he had been in contact before their election. Of the new officials, those who had not yet appeared in the diary were Nomura, Matsuoka, Shima, Umakai, Matsuda, and Iwata. Nomura was an employee at Shûeisha, so Fusatarô may well have met him on one of his visits there. Matsuda and Iwata were arsenal workers and were likely among the 'seven others' who came with Muramatsu on July 22. The nominations for the official posts would most likely have been proposed by Fusatarô himself, though almost certainly in consultation with Jô, Sawada, Suzuki and with Muramatsu Tamitarô and the other leading workers.

We shall now look at the background of these men. In doing so, we shall see what kind of men Fusatarô judged to be suitable as officials at the very beginning of Kiseikai, and the men with whom he was to work as comrades and fellow campaigners.

Of the secretaries, we shall discuss Katayama in detail later; suffice it to say here that at the beginning of Kiseikai, he was the one of the men Fusatarô relied upon the most with Suzuki Jun'ichirô. This is evident from the fact that only Takano Fusatarô and Katayama Sen served in all three official posts - 'campaign member', 'public meetings member', and 'campaign literature member'. Sawada was, of course, Fusatarô's old comrade from his San Francisco days and ran a western-style tailoring shop first in Kyôbashi and later in Ginza.

Of the other secretaries, Muramatsu Tamitarô was the most significant man who belonged to working classes. Ironworkers formed the overwhelming majority of the Kiseikai, and among its members, the Tokyo Arsenal workers were the strongest group.

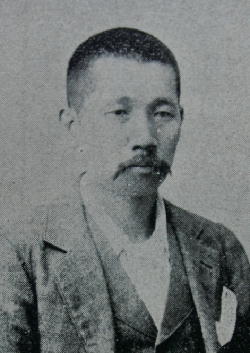

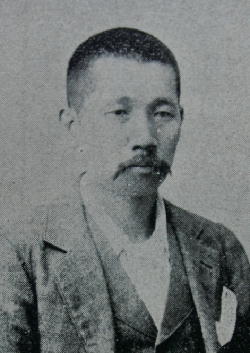

Muramatsu was a joyaku (lit. assistant official) in the bullet shop at the Arsenal. Joyaku had the highest status of workers at the arsenal, and Muramatsu led more than 80 cartridge inserting workers. He was a veteran at the arsenal, having worked there for more than ten years, but his photograph shows him looking not so old, an experienced worker aged from the late 30s to the early 40s. The decoration he wears on his left breast is most likely the one he won for distinguished service in the Sino-Japanese War. The Tokyo arsenal produced weapons for the Imperial army, and with over 4,000 workers employed there in 1897, it was the largest center of manufacturing in the capital. Whereas the Osaka arsenal produced artillery weapons such as howitzers, the Tokyo arsenal concentrated mainly on small arms: rifles, pistols and bullets. As the arsenal was such a large-scale operation, it naturally consisted of many workshops. Muramatsu who worked as the top position of a workshop of this giant industrial enterprise, willingly called at Fusatarô's house, together with seven colleagues. Muramatsu was a joyaku (lit. assistant official) in the bullet shop at the Arsenal. Joyaku had the highest status of workers at the arsenal, and Muramatsu led more than 80 cartridge inserting workers. He was a veteran at the arsenal, having worked there for more than ten years, but his photograph shows him looking not so old, an experienced worker aged from the late 30s to the early 40s. The decoration he wears on his left breast is most likely the one he won for distinguished service in the Sino-Japanese War. The Tokyo arsenal produced weapons for the Imperial army, and with over 4,000 workers employed there in 1897, it was the largest center of manufacturing in the capital. Whereas the Osaka arsenal produced artillery weapons such as howitzers, the Tokyo arsenal concentrated mainly on small arms: rifles, pistols and bullets. As the arsenal was such a large-scale operation, it naturally consisted of many workshops. Muramatsu who worked as the top position of a workshop of this giant industrial enterprise, willingly called at Fusatarô's house, together with seven colleagues.

Later, we shall examine the reasons why so many arsenal workers joined Kiseikai and what hopes they had of it, but one point can be mentioned here: in February 1897, shortly before Kiseikai was launched, Muramatsu Tamitarô was the President of the Kôgyô Dantai Dômeikai (KDD; the League of Industrial Organizations). KDD membership was aimed at senior ironworkers and was supported by contributions based on its membership fees; the organization sought to set up and manage its own factory, the purpose of which was to train ironworkers' skill. Muramatsu's influence extended not only to the Tokyo arsenal but much further afield.

Another of the Kiseikai secretaries, Yamada Kikuzô, was an official of the Tokyo Bookbinders' Union. An announcement of his change of address was carried in the very first issue of Rôdô Sekai (Labor World): Yamada Kikuzô, Tokyo Bookbinders' Union office, 1-4 Mikawachô, Kanda ward.

Of the ten standing committee members, two were printworkers at Shûeisha: Nomura Shû and Koide Kichinosuke. We have already mentioned Koide as a skilled western-language typesetter and proof-reader. The number of Shûeisha employees connected to Kiseikai was, of course, because the owner, Sakuma Tei'ichi, was a powerful supporter of Kiseikai. Shûeisha had two plants in Tokyo, which accounted for about 1,000 employees. There were not more than 8,000 printworkers in the whole country, and 3,300 of them were in Tokyo, which gives an idea of the size of Shûeisha. However, a surprisingly small number of printworkers actually joined Kiseikai, 45 at most. It is a remarkably small number compared to the over 2,500 ironworkers who became members. The five standing committee members, Ishizu Magoichi, Umakai Chônosuke, Mamie Kintarô, Matsuda Ichitarô, and Iwata Sukejirô, were all ironworkers. Ishizu and Umakai were employees at the Ministry of Communications and Transportation's equipments factory, while Mamie, Matsuda and Iwata worked at the Tokyo arsenal. All of them would become officials in the Ironworkers' Union formed at the end of the year, so their place of work is known. Standing committee member Shima Shukusaburô was a shoemaker; he was most likely proposed by Jô Tsunetarô. Details for the remaining two are unknown. Tanaka Tarô spoke at public meetings and wrote under the pseudonym 'a worker' for Rôdô Sekai (Labor World). Matsuoka Otokichi's occupation is also unknown; there is no-one of that name among the officials of the Unions.

Support for Kiseikai from the Crown Prince's uncle

At first, Takano Fusatarô had intended that the leading members of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions would be 'intellectuals', especially labor researchers such as the members of the Social Policy Association, but the members of the Association who joined Kiseikai were only his own brother Iwasaburô and Suzuki Jun'ichirô. But both of them went aboard to pursue their studies: Suzuki in June 1898 and Iwasaburô in June 1899. The two on whom he had relied the most were therefore not in Japan just at the time that their help was most needed. Other Social Policy Association members such as Kanai Noburu, Kuwata Kumazô, and Tajima Kinji understood labor issue and could have joined Kiseikai but did not. Katayama was also a member of the Association, but he got the membership by Suzuki's introduction after he had joined Kiseikai. Those intellectuals who did participate in Kiseikai were as follows:

∗ Council members...... Sakuma Tei'ichi, Suzuki Jun'ichirô, Shimada Saburô, Hino Sukehide, Murai Tomoyoshi, Abe Iso'o.

∗ Public speakers...... Sakuma Tei'ichi, Shimada Saburô, Takano Iwasaburô, Suzuki Jun'ichirô, Miyoshi Taizô, Matsumura Kaiseki, Kaneko Kentarô.

∗ Rôdô Sekai (Labor World) editors...... Yokoyama Gen'nosuke, Uematsu Kôshô, Nishikawa Mitsujirô.

∗ Rôdô Sekai (Labor World) contributors...... Charles Garst (Tanzei Tarô="Single-tax John"), Murai Tomoyoshi, Abe Iso'o, Uchida Fuchian (Roan), Takano Iwasaburô, Kôtoku Shûsui, Kawakami Kiyoshi, Itô Tamekichi.

'Council members' were a kind of 'advisory board' for Kiseikai. The most noteworthy among them was Count Hino Sukehide. Born in 1863 the fifth son of Yanagihara Mitsunaru, a court noble. Sukehide was legally adopted into the Hino family and received the title of Count. His elder sister was Yanagihara Naruko, the birth mother of the Emperor Taishô. In 1888 Hino Sukehide had been appointed to the service of Crown Prince Harunomiya (later the Emperor Taisho) and had been sent to study in England at the University of London, where he read economics and social studies. In 1894 he returned to Japan and was appointed Chamberlain of the Crown Prince's Household, but the following year he resigned and took a seat in the House of Peers. While studying in England, he had gotten to know Machida Chûji; a politician and the founder of Tôyô Keizai Shinpô (Journal of Oriental Economics), Count Hino supported Machida financially at the time of the launch of the Journal.

As a 'friend of the Tôyô Keizai Company', Hino wrote many pieces for the journal. He was also a guest member of the Social Policy Association.

It was rather peculiar that 'the uncle of the Crown Prince' and a man who was very close to the imperial family should have studied social questions abroad, further that after returning to Japan he should be appointed council member of the Kiseikai; a supporting group for labor unions, write the preface to Yokoyama Gen'nosuke's Nihon no kasô shakai (The Lower Class Society of Japan), and at the general meeting of the Ironworkers' Union give a lecture titled 'Relations between Employers and Employees in England' that covered two pages in the magazine Rôdô Sekai (Labor World) is astounding. There have always been members of the ruling class who have shown compassion and sympathy for the common people, but there have not been many who have shown public support for the labor union movement and attended and spoken at its meetings. It was no doubt possible because at that time the image of the movement in the minds of the upper classes had not yet become such a fixedly negative one. The early years of the trade union movement was a period in which a remarkable constellation of individuals stepped forward to support it such as Count Hino Sukehide and the former Minister of Agriculture and Commerce Kaneko Kentarô, who gave a great speech in support of labor unions at a Kiseikai meeting.

Kiseikai council member Murai Tomoyoshi graduated from Dôshisha Academy, the forerunner of Doshisha University, then studied at Andover Theological Seminary; the oldest graduate school of theology in the USA, at which the founder of Doshisha, Joseph Hardy Neesima had studied. Murai later focused on English language education, becoming a professor at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages. Along with Abe Iso'o, he was a member of the Association for the Study of Socialism (Shakaishugi kenkyukai).

Abe had also graduated from Dôshisha and had gone on to study at Hartford Theological Seminary in the United States and at Berlin University. It is said that he became convinced that only socialism could solve the problem of poverty after reading Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy in 1893 while studying in America. After his return to Japan, he taught at Dôshisha and then at Waseda High School. It was Abe who wrote the platform of the Shakai Minshutô (Social Democratic Party), the first socialist party in Japan, founded and banned in May 1901. He went on to become a professor at Waseda University, where he taught until he was elected to the Diet in the first general election under universal manhood suffrage. He founded the Waseda University baseball club, led the club squad on a tour of America, and made a great contribution to the development of baseball at Japanese universities.

Murai Tomoyoshi, Abe Iso'o, Nishikawa Mitsujirô, Kawakami Kiyoshi were all Christian Socialists, while Matsumura Kaiseki and Miyoshi Taizô were also Christians - they had all become involved in supporting the labor movement through their connection to Katayama Sen. Those who joined Kiseikai through Takano Fusatarô were Sakuma Tei'ichi, Suzuki Jun'ichirô, Takano Iwasaburô, as well as Count Hino Sukehide, who had become friendly with Suzuki through the Tôyô Keizai Shinpô, and Sakuma's old friend, Shimada Saburô. At any rate, that such a group of men could have been brought together in support of the labor union movement, which was hardly known in Japan at that time, is sure testimony to the effectiveness of Fusatarô's ideas.

A forgotten contributor - Suzuki Jun'ichirô

Thus far we have referred to Suzuki Jun'ichirô numerous times but only cursorily. Yet he was close to Fusatarô both in public and in private, and in the biography of Takano Fusatarô, he was someone whose role in those early days of the Japanese labor union movement cannot be overlooked. The details of Suzuki's background are little known, and in the history of the labor movement his achievements have hardly been recognized. At this point I would therefore like to shed some light on his background and on the role he played in the early labor movement.

Suzuki Jun'ichirô was born in August 1868 in the village of Nakano, Isawa County, Mutsu Province (Iwate Prefecture), so he was about four months older than Fusatarô. After graduating from teacher training school in Iwate, he studied at the School of Foreign Languages, entered the Economics Department at the Senshû College, the forerunner of Senshû University, from where he graduated in 1892. After his graduation, he became a teacher at his alma mater and gave the opening address at a conference of the Senshû College's Association for the Study of Economics. There are books which mention him as having done postgraduate studies at Yale and Princeton universities, but that is an error.

His occupation is revealed in his writings as a 'lecturer at the Tokyo Technical School or 'lecturer at Tokyo Higher Technical School'. The Tokyo Technical School, which bore this name at the time of his appointment, was renamed The Tokyo Higher Technical School in 1901, the predecessor of today's Tokyo Institute of Technology. The subject for which he was responsible was 'The Economics of Manufacturing'. He served as lecturer for a total of 14 years, from September 1895 to June 1898, and then after a period studying abroad, from November 1900 to September 1911. During the Russo-Japanese war, he was ordered by the government to go to the United States as a member of the 'Kaneko Kentarô Mission' and was put in charge of organizing the Japanese diplomatic propaganda campaign. He was out of Japan from February 1904 to October 1905, but his post as 'lecturer' remained valid during this time.

However, the post of lecturer at the Tokyo Higher Technical School was not full-time, and in 1897 his main work was at the export department of the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. Here too, the post was not a full-time, and his name was not entered into the official staff lists, but he was treated with unusual favor and for two and one half years sent to study abroad in the United States as a 'commercial observer' by the Ministry. This was decided by the Minister Kaneko Kentarô at the time of his stepping down from his office. Suzuki seems to have served as a kind of private secretary to Kaneko, and he edited Kaneko's book Keizai Seisaku (Economic Policy), which was published by Ôkura Shoten. During the Russo-Japanese War Suzuki was appointed a member of the Kaneko Mission and worked formally in the position of secretary for almost two years. Kaneko Kentarô had been involved in the founding and management of Senshû College, so he had probably gotten to know Suzuki Jun'ichirô at meetings at the College.

Meanwhile, it seems that through his brother Iwasaburô that Fusatarô became acquainted with Suzuki. Iwasaburô and Suzuki had been founding members of the Social Policy Association and were two of the few researchers in the same field, economics. Suzuki taught 'Engineering and Economic Theory' at Tokyo Technical School, while Iwasaburô's research topic in his postgraduate studies was 'The Economics of Manufacturing'. When Suzuki was away studying abroad, Iwasaburô stood in for him teaching 'The Economics of Manufacturing' at Tokyo School of Engineering. Suzuki was also the first executive secretary of the Keizaigaku Kôkyûkai (Economics Research Group). The fact that he was a recognized economics researcher and saw himself as one made him a man of great interest to Fusatarô, who had his own strong inclination towards economics.

Suzuki was a prolific writer in many areas. On current affairs he published several books, The Need for National Concern over the Foreign Residence Issue (Kokumin yôi naichi zakkyoi kokoroe) in 1894, and at the time of the Russo-Japanese War, the opportunistic and rather unscrupulous books An Account of the Japan-China-Korea War (Nisshinkan taisen jikki) and The Lives and Glorious Deaths of Our Military Men in the Sino-Japanese War (Nisshin senso gunjin meiyo chushi retsuden). He also wrote reference books such as Model Sentences for the Imperial Armed Forces (Teikoku gunjin bunkan) and even worked as a reviser of A Commentary on the Tosa Diaries (Tosa nikki shakugi). He might have had a good reputation as a writer and seems to have been well-known in publishing circles.

In his own specialist field, he published "Examples of Industrial Strikes in Japan" (Wagakuni ni okeru dômei-hikô no senrei) in Kokka gakkai zasshi (The Journal of the Political Science Association), and for the Tôyô keizai Shinpo (Journal of Oriental Economics), he wrote several articles as follows: "How to prevent from workforce-enticing" (Shokkô yûdatsu yobô hôsaku), "On the Factory Laws" (Kôjôhô seitei ni tsuite), "The Aims of the Factory Laws" (Kôjôhô seitei no mokuteki), "The so-called workforce-enticing issue" (Iwayuru shokkô yûdatsu mondai) and "The management of workingmen at the Krupp Ironworks" (Kuruppu tekkôjô shokkô kanri jijô). Suzuki was not only a contributor of articles to the Tôyô keizai; like Hino Sukehide, he was continually in and out of the editorial office of Tôyô Keizai, as a 'friend of the company' (shayû). This must have been facilitated by the fact that his home was very close to the office of the Tôyô Keizai Shinpô.

Suzuki Jun'ichirô was not only the kind of 'friend of the workers' that Fusatarô had long looked for, but was also an important personal friend. It is noteworthy that when the movement got underway in the first half of 1897 and Suzuki was concerned about Fusatarô's livelihood, he helped him out in various ways, for example, by securing for him the translation work at the Exported Goods Office and the post of 'commercial products exhibition hall assistant'. This job, which paid a daily wage of one yen a day, offended Fusatarô's self-respect, and he soon noted, "Not a very interesting opportunity". It was also Suzuki who introduced Fusatarô to Ôkura Shoten, which published the Wa-Ei Jiten (Japanese-English Dictionary) and the Ei-Wa Shôgyô Kaiwa (English-Japanese Business Conversation) which Fusatarô had authored. The two men also socialized and often went for a drink together.

Like Sakuma Tei'ichi, Suzuki was not only Fusatarô's personal friend but a powerful supporter of Kiseikai. He was the adviser Fusatarô most relied on at the time of the founding of Kiseikai. He donated over half the costs of the founding meeting and was the only speaker at the event. At the first monthly meeting, he and Sakuma Tei'ichi were selected as 'councilors'. This was no empty formal title; they frequently attended the regular monthly meetings and spoke their minds. Incidentally, Suzuki was also the first Japanese labor song writer. In April 1898, when Kiseikai planned a May Day demonstration march, he wrote a marching song.

The year of his death is unknown, but in 'the register of members of the Social Policy Association' included in each number of Bulletin of the Social Policy Association (Shakai seisaku gakkai ronsô), Suzuki Jun'ichiro's name appears in every one, so the year of his death is likely to have been after 1924.

Katayama Sen and Takano Fusatarô - an unbalanced appraisal

The next theme I would like to take up is that of Katayama Sen, who along with Takano Fusatarô was one of the leading figures of the labor movement of the Meiji period. One cannot speak about Takano Fusatarô without mentioning Katayama, and without mentioning Takano Fusatarô, one cannot speak about Katayama Sen's role in the early years of the Japanese labor movement.  To determine the standing of these two pioneers of the labor movement is one of the main aims of this book. I mentioned in the Foreword that the achievements of the two men within the labor movement of the Meiji period has still not been correctly evaluated. There are two reasons for this. One is prejudice due to researchers' ideological perspectives. In contrast to Takano, who was opposed to socialism, Katayama Sen was a pioneer in the Japanese socialist movement, and from the time he became a leading member of the Comintern, not a few scholars have greatly praised his contribution, more highly than it perhaps deserves. Such clear prejudice is no longer to be found among researchers in the field, but in literature outside the specialist fields of labor history and socialism, long-held prejudice still lingers on.

To determine the standing of these two pioneers of the labor movement is one of the main aims of this book. I mentioned in the Foreword that the achievements of the two men within the labor movement of the Meiji period has still not been correctly evaluated. There are two reasons for this. One is prejudice due to researchers' ideological perspectives. In contrast to Takano, who was opposed to socialism, Katayama Sen was a pioneer in the Japanese socialist movement, and from the time he became a leading member of the Comintern, not a few scholars have greatly praised his contribution, more highly than it perhaps deserves. Such clear prejudice is no longer to be found among researchers in the field, but in literature outside the specialist fields of labor history and socialism, long-held prejudice still lingers on.

The second reason has to do with the limitations of historical documents. The basic historical texts relating to this early period of the labor movement almost all written by Katayama himself. These include Nihon no rôdô undô (The Labor Movement in Japan) by Katayama Sen and Nishikawa Mitsujirô, Autobiography of Katayama Sen (Jiden), and the journal Rôdô Sekai (Labor World), which Katayama was the sole editor from the first issue to the end, and later published under his own responsibility.

In other words, we have until now been viewing the history of the early labor movement through Katayama's eyes. This is, of course, not Katayama's fault. While Takano Fusatarô left not a single essay of memoirs, Katayama, in addition to the historical records of the period he lived through, wrote three autobiographies, and a history of the Japanese labor movement in English! We can be grateful that he left us so many historical accounts, and they are certainly irreproachable. However, scholars have insufficiently examined these materials and have relied upon them unconditionally. Getting beyond this restriction presents much greater difficulty than the overcoming of ideological prejudice. The only way to proceed here will be to search out, examine, illuminate and interpret as many relevant historical records as possible.

Katayama Sen's hard road to academic status

Let us begin by looking at Katayama's path to participation in the labor movement. Born on Dec. 26, 1859 in the village of Hadeki, Kume county, in Mimasaka province (Okayama prefecture) to a farming family named Yabuki. So he was about nine years older than Takano Fusatarô. Katayama Sen's birth name was Sugatarô, which sounds like an eldest son's name, but he was, in fact, the second son. His elder brother and only sibling was named Mokutarô. His father Kunihei, who had himself been an adopted son as the husband for the Yabuki family's eldest daughter, Kichi. But Kunihei was divorced when Sugatarô was just three years old, and the two boys were brought up by their mother Kichi, who supported the family but did not remarry.

At the age of 19, Yabuki Sugatarô was adopted by the Katayama family, and he changed his name as Katayama Sen. In fact this adoption aimed only to avoid conscription, so Katayama Sen's actual situation did not change at all, he was still the second son of the Yabuki family. The Yabukis were an old family who for generations had provided the village with its headman, but as a second son Katayama Sen had been obliged to support himself. In 1881, in a bid to get ahead through study, he went up to Tokyo and worked as a printworker and caretaker at a small private school for kangaku (Chinese learning) run by Oka Kamon. But realizing that he was not sufficiently capable at kangaku to support his livelihood, he became uneasy about his future and attended Kôgyokusha; well known as a prep school for the naval academy, for a short while. At that time he was encouraged by his friend Iwasaki Seikichi, who had been to America and had written that "America is a country where you can study even if you are poor". Katayama resolved to go to America himself. He did not have the means to pay for the trip himself, so with help from Iwasaki Seikichi's father and from friends, he arrived in San Francisco in 1884. His departure was two years before Fusatarô's and at just before his 25th birthday, seven years older than Fusatarô, it was a little late to be going off to study abroad.

In America, he worked as a domestic servant, doing various jobs, cooking, waitering, cleaning, laundering, and while enduring a great deal of hard work and poverty, he saved his money and for over ten years went on with this hard life, using his money to fund his further education. He shared the company of youngsters ten years younger than himself, and after studying at the Hopkins Academy in Oakland, California and Maryville College, Tennessee, he went on to Grinnell College at Iowa where in 1892 and 1893 he graduated with a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Arts degree respectively. He then studied at the Andover Theological Seminary and then to Yale Divinity School obtaining a Bachelor of Divinity degree there in 1895. He certainly proved by his own experience the truth of Iwasaki's words: "America is a country where you can study even if you are poor".

Looking at this whole early phase of Katayama's biography, it is clear that the circumstances of his origins, his upbringing and his education show a great contrast with those of Takano Fusatarô. Whereas Fusatarô was a 'city boy', born in Nagasaki, who had spent an eventful youth in Tokyo and Yokohama, had early on harbored a desire to go to America and had prepared himself for studying abroad by learning English in Japan. Katayama Sen was born and brought up in a mountain village of the westernmost region of the main island and left Japan to study abroad without much in the way of preparation.

The two of them were sharply contrasted in their family relations. Fusatarô, as the eldest son, was burdened by his family's expectations and weighed down with the task of having to restore the fortunes of Nagasakiya. Katayama, on the other hand, the second son of a farming family, was parted for life from his natural father, who was himself an adopted son and lost his mother while he was in America. Although he received no support from his family, he was completely free of binding family ties.

In terms of their personality, Takano and Katayama were exact opposite. Fusatarô constantly looked ahead, examined everything and moved into action only after making detailed plans. He was always on the lookout to profit from any situation and quick to move on from one location to another. Katayama, by contrast, did not seek to read the future in any detail; he proceeded by trial and error. He was the kind of man who, once he had decided on his general goal, simply kept on after it no matter what hardships he had to encounter on the way, a man who went on his way clothed, so to speak, in 'endurance and stubbornness'. While Fusatarô was a city boy, the son of a merchant family, Katayama had the blood of Japanese farmers in his veins.

The differences in the personality of the two men influenced not only their participation in the social movement but also their experiences in America. Fusatarô dreamed of success in the practical world of business and paid no attention to the schooling that could get him academic credentials; he preferred the way of the self-taught autodidact.

Katayama, by contrast, applied himself persistently to higher education and obtained his qualifications through what is called in Japanese kugaku (earn his own school expenses through adversity). One gets a sense of how important for him to get academic degrees from the fact that he had the title 'Master of Arts' printed on the covers of his books, and in the advertisements for Rôdô Sekai (Labor World) he translated this title as bungaku hakushi - literally, Doctor of Literature. This inclination of his can be seen in the fact that Katayama persuaded men such as Ôkubo Toshitake and Matsukata Kôjirô, the sons of elder statesmen of the early Meiji period, who had also studied at Yale University, to form a Yale University Alumni Association in Japan.

Wherever he was in America, Fusatarô maintained his relationships with the Japanese community in America, especially those in San Francisco, and he kept to his Japanese values. Katayama, however, lived in university dormitories where there were hardly any Japanese, was influenced by American values and after his return to Japan, got into endless troubles with those around him on account of his 'rationalistic' approach to money and the strength of his self-assertion.

Before he returned to Japan, Fusatarô was already thinking of starting a labor union movement there and gathered all kinds of information in America in preparation for that aim; he even secured for himself the post of AFL organizer for Japan. Katayama Sen, by contrast, was a social reformer who focused on urban problems.

While Takano Fusatarô showed no interest whatsoever in Christianity, Katayama Sen entered the Christian faith believing it to be useful in the acquisition of higher education but ended up becoming an enthusiastic Christian. He made his post-graduate studies at Andover Theological Seminary, America's leading theological school and as a Yale Divinity School student, and sought to work within the world of Christianity. But on returning to Japan, he could find no suitable opportunity to do so. He felt that the situation was one in which "the Dôshisha group dominate Kumiai-kyôkai (Congregational church)", so I cannot work in it.

Katayama Sen's old friend - Itô Tamekichi

In this difficult situation, Katayama was aided by a man who had been his senior at Andover, the missionary Daniel C. Greene. American Protestant Christian churches had set up the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, and Greene arranged for this body to subsidize Katayama to the tune of 25 yen a month. With this money Katayama was able to rent a house at 1-12, Misaki-chô, Kanda-ku, Tokyo. Here, in the summer of 1897 he established the Kingsley Hall, the head office of the 'Christian Social Welfare Enterprise' settlement house. He planned to support himself by running a kindergarten alongside it, but his rented house was too small, and he could not obtain the necessary permission from the authority.

At that point Katayama wrote a letter to Arther L. Weatherly, a friend from his years in Grinnell College to Andover Seminary, and asked him for aid for a headquarter of social work in Tokyo he sought to establish for the sake of the propagation of Christianity.  Weatherly responded quickly to contribute an appeal to a social settlement magazine The Commons, as a result, Katayama was given US $250 (about 500 yen). With this money, he built his own premises at 3-1 Misaki-chô and in April 1898 moved the Kingsley Hall there and opened a kindergarten. The site of the Kingsley Hall is now part of the main building of the Law Faculty of Nihon University. In passing, it can be noted that the Misaki-chô area was, together with Marunouchi, bought by Mitsubishi from the military, which had used it as a training ground. Mitsubishi developed the area, constructed roads and brick-built houses for rent, and rented out the land. Nearby was the Tokyo arsenal, which was the Ironworkers' Union's main organizational base, and the combined offices of the Arsenal branch of the Ironworkers' Union was based in Misaki-chô. Weatherly responded quickly to contribute an appeal to a social settlement magazine The Commons, as a result, Katayama was given US $250 (about 500 yen). With this money, he built his own premises at 3-1 Misaki-chô and in April 1898 moved the Kingsley Hall there and opened a kindergarten. The site of the Kingsley Hall is now part of the main building of the Law Faculty of Nihon University. In passing, it can be noted that the Misaki-chô area was, together with Marunouchi, bought by Mitsubishi from the military, which had used it as a training ground. Mitsubishi developed the area, constructed roads and brick-built houses for rent, and rented out the land. Nearby was the Tokyo arsenal, which was the Ironworkers' Union's main organizational base, and the combined offices of the Arsenal branch of the Ironworkers' Union was based in Misaki-chô.

Katayama's speech at the public meeting organized by the Friends of Labor in July 1897 was one of the major turning points in his life. But that became clear to him only much later when he looked back on his life; at the time he had not yet resolved to become a labor activist. He still felt that it was his duty to be a Christian social worker. This was how he saw himself and wrote about it in his Autobiography:

In Japan today those who have raised their voices about the labor problem are three men who have all returned from America: Takano Fusatarô, Sawada Han'nosuke, and Jô Tsunetarô, and the man who has been supporting them, Suzuki Jun'ichirô. First, the three published a pamphlet, "What workers need to know" (Rôdôsha no kokoroe) and as the first step on the path of their movement, they held a public meeting on labor issues at the YMCA Hall in Kanda. I was asked to give a speech at that meeting and did so......

I was the head of the Kingsley Hall but I did not have any particular job, I wasn't making any money, and had no skill at public speaking nor was I knowledgeable about labor issues; I was just there to boost the number of speakers and I always attended and gave my speech. Gradually, people in labor circles got to know of me.....and eventually it happened that I became a labor specialist. At that time I attended various public meetings on labor problems and even joined advisory boards but I was not especially part of the executive.

In other words, until the founding of the Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai, Katayama Sen was no more than a supporter, and that did not change for a while after Kiseikai was established. But among the supporters, Katayama was the most energetic. He became really involved in the labor movement and one of its leaders after he was appointed editor of Rôdô Sekai (Labor World) at the end of 1897.

How did Takano Fusatarô and Katayama Sen come to meet? They had had no such chance during their years in America. They had been in the country at the same time, but whereas Takano spent most of his time on the west coast, by the time he first arrived in San Francisco, Katayama had already moved to Tennessee and thereafter, was mostly in the interior of the country.

The person who brought them together was most likely Katayama's old friend and neighbor after his return to Japan, Itô Tamekichi. Itô had designed the clocktower of watch and jewelry shop Hattori Tokeiten (forerunner of 'Seiko') on the Ginza in Tokyo. He was an unusual architect known for his early advocacy of earthquake-proof buildings after the Nôbi earthquake in 1891. He was an inventor much taken with dreams of perpetual motion machines. Readers of this book may be more familiar with those artistic siblings the dancer Itô Michio, the stage artist Itô Kisaku and the actor Senda Koreya - Itô Tamekichi was their father, and the father-in-law of the painter Nakagawa Kazumasa.

Itô Tamekichi and Katayama Sen had been friends and work mates at the Kôgyokusha school where they had studied and worked before going to America. After his return to Japan, Itô owned four houses in Misaki-chô, which he had built as an experiment; Katayama had stayed in one of those houses for a time as a lodger with Itô's mother Yasu, who had cared for him when he had fallen ill with smallpox. Katayama probably named his own daughter Yasu after her. That the Kingsley Hall was located in Misaki-chô was because of his connection to Itô, and it was Itô who designed and built it. The first children enrolled at the 'Misaki-chô kindergarten' - which eventually proved unable to attract enough children - were those of the Itô family, beginning with little Itô Michio.

Takano Fusatarô meanwhile, had been acquainted with Itô before he first met Kayama Sen, as is clear from his diary entry for May 18: This afternoon called on Mr Itô Tamekichi. From February 1885 to April 1887, Itô had organized the Japanese Business Association in San Francisco and was well-known among Japanese in America who were intent on trying their luck in business. Fusatarô had arrived in San Francisco in December 1886, so although it was only for a few months, the two men had had some opportunities to meet each other. With the aim of ameliorating workers' social conditions and of cultivating a spirit of self-reliance among them, Itô created an organization for workers called Shokkô Gundan (The Workers' Brigade) in September 1892. Fusatarô's visit to Itô was probably because he had gotten to know of this organization and was seeking to link Itô's group with his own campaigns.

Dauntless and imposing - Takano Fusatarô as a public speaker

Following its formation, the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions (Rôdôkumiai Kiseikai) put its main energies into organizing public meetings. The first of these was held at the YMCA Hall in Kanda on July 18, soon after the founding of the Kiseikai, and there were 33 known lecture meetings and panel discussions held in the first year of operation - a pace of one every ten days. At the larger meetings there were over 1200 in the audience. Fusatarô was present and spoke at all of those meetings. The next most frequent speaker was Katayama Sen, and of the seventeen meetings where the speakers' names are known, he spoke at thirteen of them. Other speakers spoke much less frequently: Suzuki Jun'ichirô and Shimada Saburô spoke at three meetings each, and Sakuma Tei'ichi, Takano Iwasaburô, and Murai Tomoyoshi at two meetings each. Matsubara Iwagorô, Saji Jitsunen and Charles Garst, Miyoshi Taizô and Tomeoka Kôsuke each spoke at one. It is noteworthy that of the members who were workers, some regular public speakers emerged, such as Takahashi Sadakichi of the Tokyo Arsenal, who spoke seven times, and Mamie Kintarô spoke four times; he was also from the Arsenal, where he worked as a fitter.

Public meetings were a form of entertainment in those days, which is hardly imaginable today. There was no television or professional baseball; it was a time when 'moving pictures' had only just begun and were limited to things such as film of the Niagara Falls, so people were prepared to pay money to go and hear someone speak in public. It cannot have been easy to satisfy audiences that were used to such fare. To stand in front of an audience the size of those that could be accommodated in the great lecture hall of the two-story YMCA Hall and deliver a speech to them without a microphone must have been a labor that called for quite some physical strength.

We can get an impression of what kind of speaker Fusatarô was from the memoirs of a Society member who was present at the very first such public meeting. It was written by "MI (Ishizu Magoichi?) of the Ironworkers' Union" and is a little unclear in places, but as it was written only a year after the event, the impression given is all the stronger.

I recall last July. Everyone was talking about it. A large public meeting about labor issues tonight at the YMCA Hall in Kanda at 6 o'clock....I straightaway rushed off to the meeting. There were already no reserved seats left....and who appeared but the present secretary, the dauntless and imposing Mr. Takano Fusatarô. In a steely voice that sounded rough, he took the position of the so-called national economy and laid into the free trade party.

The words 'dauntless and imposing' give a rather boastful impression. Fusatarô was small in stature, and to describe him as 'imposing' seems odd, but he must have seemed larger on the speakers' podium. What is meant by in a steely voice that sounded rough is hard to imagine. It certainly does not sound like a very pleasing sound to the ear. To speak to an audience of well over a thousand people without a microphone in a large hall he would have had to shout at the top of his lungs. The scene at another such public meeting, held in February of the following year, was recorded in the Labor World (Rôdô Sekai):

Labor Lecture at the YMCA Hall

A public meeting of speeches on the theme of labor was held at the YMCA Hall in Kanda on the evening of February 2nd last. It was a very cold, rough, windy day of most inclement weather but the audience, although very small, still numbered over 300. They all listened to the speeches with great excitement and what they got in recompense for their efforts in braving the cold in order to attend was a great deal.

There were five speakers: Mr Katayama, Mr Takano, Mr Tomeoka, Mr Takahashi and Mr Takebayashi, who addressed their listeners in speech that was alternately heroic, sad, cheerful and which made them weep, roused them to anger, drew forth their admiration or else consoled them...

Mr Takano Fusatarô's speech, full of righteous indignation, was tragic in its resolve, painstaking, both accusing and pleading. He raised the issue of a destructive labor movement and chilled the hearts of his listeners with the prospect. But the persuasive point about his speech was that from beginning to end he advocated peaceful means, concluding that the labor movement must avoid becoming a destructive movement. It was a most convincing speech. He ended by crying out that if Japan's capitalists and workers really understand the true labor movement, then the phrase 'destructive labor movement' would disappear that evening and leave no further trace in our country. The meeting ended at 9.30 p.m.

In other words, Fusatarô's speeches always railed bravely with righteous indignation against social injustice continually emphasizing the need for 'peaceful means' and painstakingly and carefully explaining that the labor movement needed to be 'a movement that avoids becoming destructive'.

Finally, let us take a look at the costs of the first public meeting held by Kiseikai on July 18, 1897. The extremely interesting results show the behind-the-scenes aspects that did not get into the newspapers:

| Costs |

|---|

| item | price |

|---|

| Straw sandals 500 pairs | 6 yen |

| Wages for 5 footwear-attendants at the entrance | 2 yen 25 sen |

| YMCA Hall Electric lighting 1 hour@ 1 yen 25 sen | 5 yen |

| YMCA contribution | 3 yen |

| Wage for cleaner | 50 sen |

| Oil & candles | 11 sen |

| Thank you money for 2 attendants | 1 yen |

| Printing cost of 5000 flyers | 2 yen 50 sen |

| Printing cost of 200 entrance tickets | 35 sen |

| 3 pencils | 6 sen |

| Thank you money for 4 boys (attendants) | 50 sen |

| Paper | 60 sen |

| Thank you money for the YMCA secretary | 1 yen |

| Tea and cakes | 26 sen |

| Publicity costs (wages and transport) | 25 sen |

| Postage for publicity via Tokyo Industrialists Association | 1 yen 25 sen |

| Total | 24 yen 63 sen |

The largest cost was footwear and wages for footwear-attendants accounted for a third (8 yen 25 sen) of the total costs. Although the YMCA was a newly built western-style building, one could not enter the public hall in outdoorshoes. Attendants were therefore on hand to receive outdoorfootwears, issue tickets for them and hand out straw sandals. Roads in Tokyo at that time were often muddy. Most people therefore wore geta (Japanese-style clogs), so even large, western-style public meeting halls had to have footwear attendants on hand.

The actual rental fee of the hall amounted to the 3 yen contribution to the YMCA, but one should add to that the thank you money paid to the secretaries, and to the two attendants as well as the costs of lighting, the cleaners' wages - all of this in effect should be included in the costs of hiring the hall. We see that the YMCA hall was a modern hall for public meetings and was equipped with electric lighting; at 5 yen for four hours the lighting accounted for over 20% of the total costs of hiring the hall.

The type of publicity used also emerges from the cost outlay of the meeting. Rickshaw drivers were hired to distribute flyers for the event. Tickets and flyers were also sent out by post through the Tokyo Industrialists Association's organizational network. With the formation of Kiseikai, it was not necessary for Fusatarô and his friends to bear the costs themselves personally. A total of over 28 yen in voluntary contributions was received which perfectly covered the expenditure. Fusatarô had used to complain to Gompers about the difficulty of recouping the costs of meetings from workers, but on this occasion, this awkward problem was solved unexpectedly smoothly.

Kiseikai publication - What workers need to know (Rôdôsha no kokoroe)

Besides public meetings, Kiseikai's main method of campaigning was through printed materials. "A Call to All Workers" (Shokkô shokun ni yosu) had already been produced by the Friends of Labor; Kiseikai now produced a book titled "What Workers Need to Know" (Rôdôsha no kokoroe). It cost only 3 sen, so it must have been a pamphlet like "A Call to All Workers". Unfortunately, no original of this pamphlet has survived either, so the content can only be surmised. But from publicity in Labor World, it is clear that it consisted of three sections: 1) The Nature of Work, 2) Workers' Status, 3) Labor Unions. And it is also clear from the "Publications of the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions" it was published in July 1897. As "A Call to All Workers" was rather difficult for workers to grasp, "What Workers Need to Know" was evidently written with the idea that it was necessary to produce a pamphlet that would be easy to understand for ordinary workers.

Of the twenty works cited as 'important works that directly or indirectly contributed to the labor movement', in Katayama and Nishikawa's Nihon no rôdô undô (The Labor Movement in Japan), the pamphlet "What Workers Need to Know" is mentioned as one of these, and the name of the author is given as Suzuki Jun'ichirô, most likely because Suzuki's name was mentioned in either the foreword or the colophon. However, it was not written by Suzuki alone. Fusatarô's diary records the following:

July 11 (Sun.)

Called on Suzuki at 5.30 this afternoon and handed over the text on labor unions. We then went to Mr Sawada's, returned home at 11.

July 13 (Tues.)

Called on Mr Suzuki at 9 am, at 12.30 pm we went together to Mr Sawada's. We called at Shûeisha and made the request for publication then went to Mr Sawada's and had supper. Returned home at 9 pm.

July 15 (Thurs.)

Went to Mr Sawada's this afternoon, edited the text for printing by Shûeisha and sent a report of publication to the Home Ministry.

That the text for printing by Shûeisha was in fact "What Workers Need to Know" is certain because there is a record in the 'Kiseikai Publications' (Shuppan butsu hikae) that two days later delivery was received of 2000 copies of "What Workers Need to Know" (Rôdôsha no kokoroe). Two days before the text went for printing, Fusatarô handed the text on labor unions to Suzuki, and the third chapter of that was 'Labor Unions'. In other words, we can imagine that it was Fusatarô who wrote the original text of the third chapter, and Suzuki who then made some additions. As Suzuki had authored a textbook of model sentences for soldiers, so probably Suzuki undertook to rewrite Fusatarô's manuscript to make it an easier read.

Suzuki was lecturing on 'Workers' Studies' (Shokkôron) at the Tokyo Higher Technical School'. His lectures included such topics as 'Workers' Status in the Engineering Industry', 'Women Workers', 'Child Workers', 'Workers' Unions', 'Organized Strikes', and 'Changes in Working Conditions'. He certainly had the knowledge to be able to write the first chapter, "The Nature of Work", and the second, "Workers' Status". Two days after handing over the manuscript, Fusatarô called on Suzuki again, and the two men went together to Sawada Han'nosuke's house, which had become the Kiseikai office, and they took along the text to Shûeisha to submit it for publication. It was only a pamphlet, so it could soon have been bound, edited on July the 15th and a sample copy sent off with the submission of the report of publication.

The cost of producing "What Workers Need to Know" is recorded in 'Kiseikai Publications' which states that on July 17, 1897, 2000 copies were received from Shûeisha, for which 21 yen 20 sen were paid. 150 copies were sold at the public meeting on July 18, and the rest were bought by Kiseikai members.

"What Workers Need to Know" was the "first volume in the labor collection". Kiseikai Publications states that the work was 'presented by the editors of the collection, Suzuki and Katayama', so those responsible for editing the series were evidently Suzuki and Katayama. However, only one edition of the 'labor collection' was published; it was followed by the 'Shakai Sôsho' (Social Series), which was published in just two volumes: the first, "Japan after the Foreign Residence Issue - appended to The Labor Movement in Japan" (Naichi zakkyôgo no nihon fu nihon no rôdô undô) was written by Yokoyama Gen'nosuke, and the second, Shakaishugi (Socialism), by Murai Tomoyoshi. Volume six of the Social Series included an announcement of the publication of "The Labor Movement in Japan" (Nihon no rôdô undô) by Takano Fusatarô, but no such volume actually appeared. Most likely, the plan to publish a book with this title was taken over by Katayama Sen and Nishikawa Mitsujirô.

Kiseikai members' voluntary organization

Kiseikai saw rapid growth over a short period of time. At the founding meeting on July 7, 1897, just 71 people had taken part but four months later, in November that year, the Society had more than 1,100 members. This rapid growth is well described by Katayama Sen in his testimony 'Labor in Japan' (Nihon ni okeru rôdô). Written just two years after the founding of the Society, its provides us with a vivid record. Here is a short extract:

For two or three months after [the founding], the number of people joining the Society for the Formation of Labor Unions grew vigorously. At first, printworkers were especially numerous and various other trades such as dollmakers and shoemakers, but the greatest growth came from ironworkers - especially blacksmiths, fitters and other such workers. The way we expanded our labor movement was mainly through 'agitation' lectures in various directions. People would come to hear the lectures in various places and one or two hundred of those that heard them would join up then and there. Those that heard the lectures would then spread the word to other workers in the area and talk to them about the need to form unions or would hear about their local situation - this would always provide motivation and incentive. Such was our method; we did not of ourselves go into factories to urge workers there to form unions nor did we visit workers in their homes to urge them to join the Society.

The language used is a little old-fashioned and not so clear, but three main points emerge from this: 1) the main method of expanding the organization was through public speeches, at which some 100 or 200 new members would join the Society; 2) by trade, at first most new members were printworkers and miscellaneous other trades, but the great majority were eventually 'ironworkers' who labored in metalwork and engineering trades; 3) the new recruits would themselves enthusiastically recommend the Society to their comrades and get them to join. So that Katayama and his colleagues themselves did not need to visit workplaces or workers' homes to spread the word directly. In other words, the growth of Kiseikai resulted from workers who attended the Society's public meetings and who joined the Society at those meetings and who then went on to draw in their work mates and friends so that new members multiplied prodigiously.

This is borne out by the 'Kiseikai Publications'. The Kiseikai publication "What Workers Need to Know" (Rôdôsha no kokoroe) was mainly put together and bought by activists who distributed and sold it to their friends: Mamie Kintarô bought 60 copies, Matsuoka Otokichi 59 copies, Ishizu Magoichi 45 copies, Takahashi Sadakichi 40 copies, Muramatsu Tamitarô 20 copies, and Matsuda Ichitarô 10 copies. This makes it clear that the activists got into campaigning with a will. Matsuoka Otoichi's occupation is unknown, but the others were all metalworkers; Ishizu Magoichi and his comrades all worked at the Tokyo army arsenal. Katayama says the following about them:

On reflection, many of the workers who agreed with the aims of the labor movement and joined it may have seemed frivolous and garrulous but in fact they certainly were not. The first factory workers who approached the movement were mainly senior workers, sometimes they were men who had power over many others at work, so to advance the cause of the movement in the workplace that was all to the good, and because these workers had that status, the factory owners did not oppose the movement so much. Many of these senior workers were men they could trust and if they opposed their involvement in the movement, then things could go badly for the owners. Consequently, until today there has been little reason to fear opposition.

There is reason to doubt the judgment in that last phrase until today there has been little reason to fear opposition, as the example of the Yokohama seamen's strike shows. However, the workers who joined Kiseikai certainly tended to be those of relatively higher status in factories. The Kiseikai 'Contributions Record' shows that Mamie Kintarô, Matsuda Ichitarô and others each gave 1 yen a month, while many others gave around 30 sen, so they must have been earning relatively higher wages. Along with the increase in the number of enthusiastic members, Kiseikai also rapidly developed itself as an organization. Katayama comments:

At first we hired a small place for the office of our Kiseikai - it was located in a worker's house - but gradually, as the Society became more popular, we hired rooms in the Yanagiya in Gofukuchô, Nihombashi, where there was a secretary and one activist who would be promoting the movement every day who would address workers, who would come from all quarters, about the various needs of the labor movement. Those workers who had heard about the movement in this way went on to work for the movement in various ways in their workplaces, which brought in more members. These workers would bring application forms and sign up; what developed our labor movement was the workers' own participation and energy.

The 'activist' mentioned here who was on duty every day at the office was Takano Fusatarô. The location of the first Kiseikai office - a worker's house - was the home of Sawada Han'nosuke. He lived at 1-3 Motosukiyachô, Kyôbashi-ku, next to Taimei elementary school, and hung a sign reading Beikoku saihôshi (American-style tailor) outside his tailor's shop. The Takano 'Diaries' show that Fusatarô went to Sawada's house every day from the public meeting of June 25 until mid-August. But with the rising numbers of new members and visitors, and the increasing amount of office work to get through, Sawada's shop was soon no longer adequate, and the Society began to look for other premises ahead of their first regular meetings.

On August 19, Fusatarô went to look at a house for rent in Nihombashi-ku, but it was not suitable, so they had no choice but to hold a room at the Yanagiya where they had the first meeting, at a cost of 5 yen a month. The location was in block 1, Gofukuchô, Nihombashi ward; today it is the front garden of the main branch of Mizuho Shintaku Bank.

In Fuastarô's diaries, the first appearance of the phrase 'went to the office' is on August 27; after that the words went to Mr Sawada's disappear and are replaced by went to the office. At that time, Fusatarô was living at 31 Komagome-Oiwakechô, Hongo-ku, from where his days of traveling to the office began.

Finally, let us briefly look at the occupational and regional backgrounds of Kiseikai's members in its most energetic period, October 1898, when membership numbered 2,717. By occupation, the most numerous were ironworkers (2,554), 94% of the total. These men hailed from eight regions: Tokyo, Ômiya, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Fukushima, Aomori, Morioka, and Hokkaido. The remainder included 57 woodworkers from Morioka, 45 printworkers from Tokyo, 18 shoemakers from Tokyo and 2 from Kôbe, 15 ship carpenters from Yokohama and 2 from Tokyo. There were 11 other trades from Tokyo and Hirosaki, 9 railroad workers from Ichinoseki and 1 from Tokyo, and 3 dollmakers from Tokyo. Why there were so many ironworkers and why other kinds of workers did not join, we shall leave as a subject for later investigation.

This is the English translation of the book Rôdô wa shinsei nari ketsugô wa seiryoku nari; Takano Fusatarô to sono jidai,(Iwanami Shoten Publishers, 2008.), Chapter 9 Rodokumiai kiseikai no hitobito

|

The date of the founding meeting has sometimes been given as July 3 or July 4, but that is also a mistake. Fusatarô's diary records in the column for July 5 that

The date of the founding meeting has sometimes been given as July 3 or July 4, but that is also a mistake. Fusatarô's diary records in the column for July 5 that  Muramatsu was a joyaku (lit. assistant official) in the bullet shop at the Arsenal. Joyaku had the highest status of workers at the arsenal, and Muramatsu led more than 80 cartridge inserting workers. He was a veteran at the arsenal, having worked there for more than ten years, but his photograph shows him looking not so old, an experienced worker aged from the late 30s to the early 40s. The decoration he wears on his left breast is most likely the one he won for distinguished service in the Sino-Japanese War. The Tokyo arsenal produced weapons for the Imperial army, and with over 4,000 workers employed there in 1897, it was the largest center of manufacturing in the capital. Whereas the Osaka arsenal produced artillery weapons such as howitzers, the Tokyo arsenal concentrated mainly on small arms: rifles, pistols and bullets. As the arsenal was such a large-scale operation, it naturally consisted of many workshops. Muramatsu who worked as the top position of a workshop of this giant industrial enterprise, willingly called at Fusatarô's house, together with seven colleagues.

Muramatsu was a joyaku (lit. assistant official) in the bullet shop at the Arsenal. Joyaku had the highest status of workers at the arsenal, and Muramatsu led more than 80 cartridge inserting workers. He was a veteran at the arsenal, having worked there for more than ten years, but his photograph shows him looking not so old, an experienced worker aged from the late 30s to the early 40s. The decoration he wears on his left breast is most likely the one he won for distinguished service in the Sino-Japanese War. The Tokyo arsenal produced weapons for the Imperial army, and with over 4,000 workers employed there in 1897, it was the largest center of manufacturing in the capital. Whereas the Osaka arsenal produced artillery weapons such as howitzers, the Tokyo arsenal concentrated mainly on small arms: rifles, pistols and bullets. As the arsenal was such a large-scale operation, it naturally consisted of many workshops. Muramatsu who worked as the top position of a workshop of this giant industrial enterprise, willingly called at Fusatarô's house, together with seven colleagues.

To determine the standing of these two pioneers of the labor movement is one of the main aims of this book. I mentioned in the Foreword that the achievements of the two men within the labor movement of the Meiji period has still not been correctly evaluated. There are two reasons for this. One is prejudice due to researchers' ideological perspectives. In contrast to Takano, who was opposed to socialism, Katayama Sen was a pioneer in the Japanese socialist movement, and from the time he became a leading member of the Comintern, not a few scholars have greatly praised his contribution, more highly than it perhaps deserves. Such clear prejudice is no longer to be found among researchers in the field, but in literature outside the specialist fields of labor history and socialism, long-held prejudice still lingers on.

To determine the standing of these two pioneers of the labor movement is one of the main aims of this book. I mentioned in the Foreword that the achievements of the two men within the labor movement of the Meiji period has still not been correctly evaluated. There are two reasons for this. One is prejudice due to researchers' ideological perspectives. In contrast to Takano, who was opposed to socialism, Katayama Sen was a pioneer in the Japanese socialist movement, and from the time he became a leading member of the Comintern, not a few scholars have greatly praised his contribution, more highly than it perhaps deserves. Such clear prejudice is no longer to be found among researchers in the field, but in literature outside the specialist fields of labor history and socialism, long-held prejudice still lingers on.

Weatherly responded quickly to contribute an appeal to a social settlement magazine The Commons, as a result, Katayama was given US $250 (about 500 yen). With this money, he built his own premises at 3-1 Misaki-chô and in April 1898 moved the Kingsley Hall there and opened a kindergarten. The site of the Kingsley Hall is now part of the main building of the Law Faculty of Nihon University. In passing, it can be noted that the Misaki-chô area was, together with Marunouchi, bought by Mitsubishi from the military, which had used it as a training ground. Mitsubishi developed the area, constructed roads and brick-built houses for rent, and rented out the land. Nearby was the Tokyo arsenal, which was the Ironworkers' Union's main organizational base, and the combined offices of the Arsenal branch of the Ironworkers' Union was based in Misaki-chô.

Weatherly responded quickly to contribute an appeal to a social settlement magazine The Commons, as a result, Katayama was given US $250 (about 500 yen). With this money, he built his own premises at 3-1 Misaki-chô and in April 1898 moved the Kingsley Hall there and opened a kindergarten. The site of the Kingsley Hall is now part of the main building of the Law Faculty of Nihon University. In passing, it can be noted that the Misaki-chô area was, together with Marunouchi, bought by Mitsubishi from the military, which had used it as a training ground. Mitsubishi developed the area, constructed roads and brick-built houses for rent, and rented out the land. Nearby was the Tokyo arsenal, which was the Ironworkers' Union's main organizational base, and the combined offices of the Arsenal branch of the Ironworkers' Union was based in Misaki-chô.